Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana and the wind and rain damaged our coasts. These images show the damage created.

Satellite photos taken six weeks after Hurricane Ida blasted southeast Louisiana show its storm surge, waves and winds devastated a large swath of wetlands in the north central Barataria Basin, gashing a coastal buffer that helps protect 1 million people from flooding. The European Space Agency Sentinel 2 images, captured before Ida on Feb. 1 and afterward on Oct. 9, indicate that the wetlands adjacent to the southeast corner of the failed Delta Farms property, a shallow lake, are now connected by newly created open water to Little Lake in the northern basin near Lake Salvador. Wetlands to the south of that area and east of Clovelly Farms have also disappeared. And numerous breaches in wetlands have formed on the north and south sides of a canal running along the southern border of Lake Salvador, turning what had been solid green wetlands on the canal’s south side into a collection of wetland patches and open water.

nola.com

EUROPEAN SPACY AGENCY SENTINEL 2 PHOTO

The area hit is part of the protection sites that money, a lot of money, has been spent to save from hurricanes.

The images show the Category 4 hurricane delivered at least a temporary knockout to this part of a fragile coast that is the focus of a $50 billion, 50-year effort to restore and protect the southern third of the state from disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico. The wetland areas ripped up by Ida just south of Lake Salvador on Aug. 29 include a mix of: Freshwater marsh, Flotant, which is a mix of wetland plants whose roots extend through water to anchor into bottom sediments and Floating marsh plants not connected to the subsurface. When healthy, flotant mats often are strong enough to hold the weight of adults walking across it. But they also allow the plants to move up and down with tidal water levels. “That many of the changes in central Barataria have persisted for as much as 40 days post-landfall lends itself to the interpretation that what we observe in these images may unfortunately be indicative of real wetland loss,” said Brady Couvillion, a geographer with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Wetland and Aquatic Research Center in Baton Rouge. “How long that loss will persist remains to be seen.” “These marshes can float at times, or can loosely rest on a soft soil beneath,” Couvillion said. “In some cases, vegetation can send roots through the flotant mat and loosely attach to the soil underneath. It appears the majority of the wetlands affected by Hurricane Ida were this type of loosely attached flotant marsh.”

This map shows initial estimates of storm surge heights during Hurricane Ida. The surge was accompanied by waves that might have been half again as high as the surge heights, and rainfall. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS GRAPHIC

There is the possibility that areas shown as open water may not be open but covered by vegetation.

Couvillion said some of the photographed areas that appear to have converted to open water actually had been covered by by floating aquatic vegetation not rooted to the soil, and thus don’t really represent newly open water. He said it’s often difficult to differentiate between the vegetation types in satellite photos. And some areas that seem to be open water, such as near Myrtle Grove, might still be the result of Ida storm surge that hasn’t drained yet. “We may see this area rebound, as vegetation may move into what is usually a relatively low-energy environment and begin to colonize, first as floating aquatic vegetation, then potentially as flotant marsh,” Couvillion said. “However, we cannot say if or when that will occur.” The storm struck 14 years into the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s continuing efforts to save the state’s 20 southern parishes from vanishing. “The reports of damage comport with what we’re seeing with the amount of debris in canals and ditches along the areas hit by the storm,” said Bren Haase, executive director of the coastal authority. “Immediately following the storm, flying over Lake Salvador, a lot of the marsh was displaced into the lake itself, and it was difficult to see where the shoreline of the lake was.” Water levels have dropped since that flight, but significant losses of wetland grasses remain evident.

COASTAL PROTECTION AND RESTORATION AUTHORITY PHOTO

Storm surge damages the land as the water sweeps across the land in both directions as the water sweeps over then retreats.

According to Army Corps of Engineers initial estimates, storm surge from Ida reached heights of 6 to 7 feet near Lafitte, which is near the Lake Salvador’s southeast corner. The surge was topped by waves likely half again higher, as Ida’s more powerful eastern side crossed the area Aug. 29. The hurricane packed top winds of almost 140 mph as its eye cut across Port Fourchon, just to the south, and continued north along Bayou Lafourche. In Little Lake and Barataria Bay, just east of Galliano and Golden Meadow, which are are protected by hurricane levees, surge heights were estimated by the Corps at 12 to 14 feet, again topped by waves half again as high. In addition to the satellite photos, evidence of the rapid erosion caused by surge and waves comes from aerial drone photos taken by Elevated Services LLC of an area of newly open water just east of Clovelly Farms, where solid wetlands were present just days before the storm. And the grass debris from the attached and floating wetlands have been identified by the coastal authority in reports to the Corps of damage to the levee systems. The debris must be removed to assure that grass growing on the wet side of the levees, which acts as armoring against surge damage from future hurricanes, isn’t killed.

While Ida hurt us, the damage was not as bad as other hurricanes we have experienced in the past.

Ida’s damage to the natural elements of Louisiana coast were likely not as extensive as that of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, which destroyed more than 200 square miles of wetlands in 2005. Ida’s most significant wetland damage occurred in areas just north of where restoration efforts have aimed at rebuilding “land bridges,” new wThough initially stacked with enough soil to be above the surface of the water, the new land area will eventually sink enough to be colonized by wetland grasses that will be inundated during high tides. In addition as acting as speed bumps to future storm surges, the land bridges also help reduce saltier water from the Gulf of Mexico from reaching freshwater wetlands and the intermediate flotant wetlands, like those near Lake Salvador. etland platforms of solid sediment and sand extending west from the Mississippi River through Plaquemines and Lafourche parishes.

COASTAL PROTECTION AND RESTORATION AUTHORITY GRAPHIC

There are three major factors which have caused the damage, and of course oil is one of them. Yet others can be laid at our feet.

The three major reasons for Louisiana’s coastal loss are hurricanes, saltwater intrusion from oil and gas exploration activities and lack of replenishing sediment since the Mississippi River was leveed in the early part of the 20th century. Charles Sasser, a Louisiana State University research professor . “You would expect there to be some natural regrowth of the marsh, but the critical thing for these buoyant marshes is to have fresh or nearly fresh water,” Sasser said. “That’s been the battle for decades in the Barataria Basin and other places.”specializing in wetland plant ecology, warns that restoring the flotant marsh area might prove difficult, now that part of it has converted to open water.

We must continue to fight for conservation of the land.

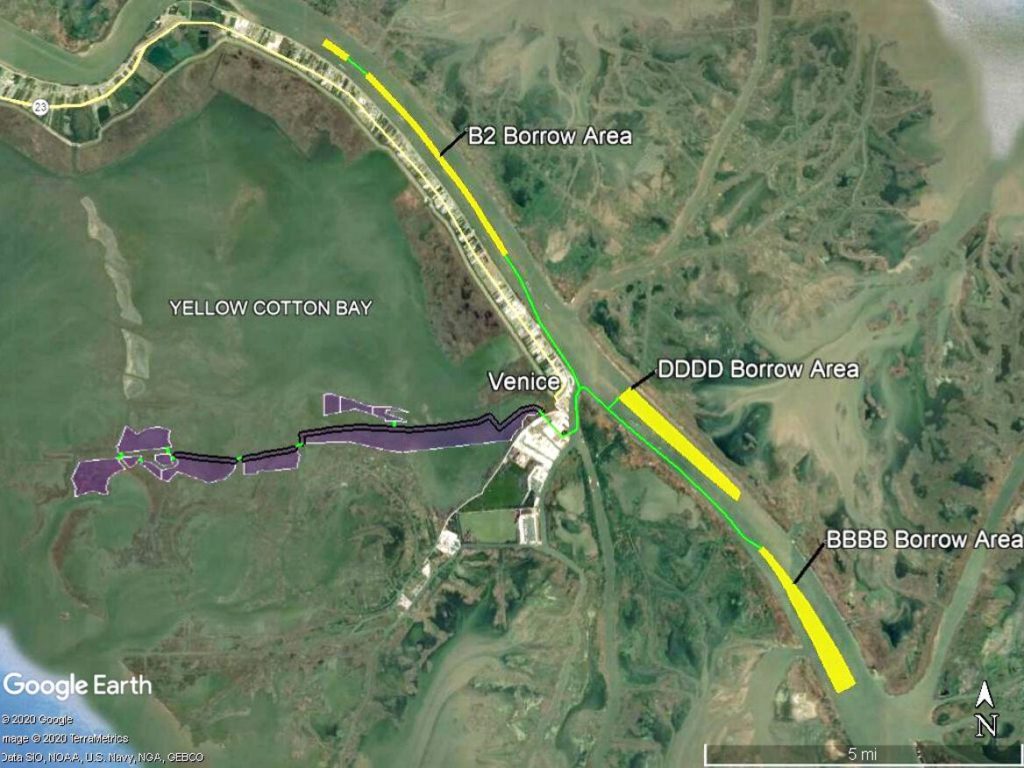

That battle might depend on the broader success of state officials to build land bridges of sediment mined from the Mississippi River and pumped inland to be used as a nursery for new wetland grasses. The long stretches positioned strategically east-west within the Barataria Basin will help reduce the flow of saltier water from the Gulf to the northern parts of the basin. Also assisting could be the controversial Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, proposed for construction just east of the Delta Farms area. The diversion is to add sediment that will end up atop existing wetlands, and to build new wetland areas just west of Myrtle Grove. While it will operate at its 75,000 cubic feet per second maximum for a short part of the year, usually in spring and summer months when the river is at its highest, the plan is to allow about 5,000 cubic feet per second of freshwater to flow through the structure year-round, which could help in keeping the upper Barataria area fresh enough to assist the flotant plants. “The cool thing about floating marsh is if it is in a somewhat protected area, if it’s not subject to intense wave or wind action or tidal action, they can maintain themselves,” Sasser said. “They have that advantage over marsh attached to the water bottom. But they’re at a real disadvantage when salinity levels are increasing.”

Additional the state is involved in other areas for protection of our land.

State officials also are tracking: Erosion caused by Ida surge and waves of shoreline areas along the Cheniere Caminada headland, stretching between Port Fourchon and Elmer’s Island, The destruction of levees along the south side of Grand Isle and Erosion of beach areas along West Grand Terre Island.

Saving coastal Louisiana will continue to take time and money, but what other option is there?