Many carbon capture bills were proposed but only one passed. What does it say?

Louisiana lawmakers shot down more than half a dozen bills to address concerns around carbon capture, but one proposal survived the session’s final chaotic moments last week. House Bill 571, by House Speaker Clay Schexnayder, R-Gonzales, would give local governments a chunk of revenue from carbon stored under state land or water bottoms. The speaker cast his bill as a middle ground in the debate on the controversial technology. “If you’re for carbon capture, this is a great bill,” Schexnayder said at a House committee meeting in April. “If you’re against carbon capture, this is still a great bill. This is an insurance policy for you back home.” Carbon capture and storage is a process where industrial facilities contain their carbon dioxide emissions to inject and store them below ground instead of releasing the gas into the atmosphere.

laliiuminator.com

Carbon capture is not loved by all especially in my back yard.

Louisiana lawmakers shot down more than half a dozen bills to address concerns around carbon capture, but one proposal survived the session’s final chaotic moments last week.

House Bill 571, by House Speaker Clay Schexnayder, R-Gonzales, would give local governments a chunk of revenue from carbon stored under state land or water bottoms.

The speaker cast his bill as a middle ground in the debate on the controversial technology.

“If you’re for carbon capture, this is a great bill,” Schexnayder said at a House committee meeting in April. “If you’re against carbon capture, this is still a great bill. This is an insurance policy for you back home.”

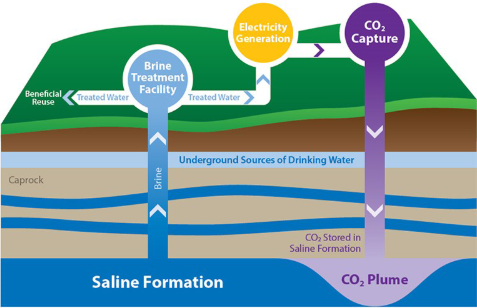

Carbon capture and storage is a process where industrial facilities contain their carbon dioxide emissions to inject and store them below ground instead of releasing the gas into the atmosphere.

Carbon capture is not loved by all especially in their back yards.

Louisiana lawmakers shot down more than half a dozen bills to address concerns around carbon capture, but one proposal survived the session’s final chaotic moments last week.

House Bill 571, by House Speaker Clay Schexnayder, R-Gonzales, would give local governments a chunk of revenue from carbon stored under state land or water bottoms.

The speaker cast his bill as a middle ground in the debate on the controversial technology.

“If you’re for carbon capture, this is a great bill,” Schexnayder said at a House committee meeting in April. “If you’re against carbon capture, this is still a great bill. This is an insurance policy for you back home.”

Carbon capture and storage is a process where industrial facilities contain their carbon dioxide emissions to inject and store them below ground instead of releasing the gas into the atmosphere.

Carbon capture is not loved by all especially in their back yards.

Proposed projects have drawn the ire of neighboring residents who worry about their safety and ecological damage. Environmentalists say the technology enables continued fossil fuel reliance. Other bills to limit carbon capture failed this session, including from Republican lawmakers aiming to halt a proposed project around Lake Maurepas, just west of Lake Pontchartrain. The speaker’s bill was a lone survivor. Without debate, changes to the proposal agreed to in a conference committee Thursday shot through the Senate with 20 minutes to go in the session and was approved in the House with less than 4 minutes to spare. The Senate vote was unanimous, and the House vote was 83-9. Now, the bill’s fate lies with Gov. John Bel Edwards, who typically waits to state his position on legislative proposals once they reach his desk. Edwards has made carbon capture a key part of his goal to get the state to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, and the petrochemical industry has been eager to oblige. There are at least 20 carbon storage sites planned for Louisiana, according to a recent Empower report commissioned by the nonprofit 2030 Fund.

Local governments get 30% of the revenue generated.

Under the speaker’s bill, 30% of revenues from carbon storage under state land or water bottoms would go to local governments. If a project spans multiple parishes, the money will be divided in accordance to the amount of area it occupies in each parish. An equal cut will go to a special fund in the state treasury called the Mineral and Energy Operation Fund, which pays for energy industry regulation. The remainder will go to the state general fund. Schexnayder said in April his bill would make sure locals get something out of carbon capture projects. “If we leave it alone and nothing happens, we get nothing but a small piece of property tax, especially if it’s on a state piece of property,” he said. Schexnayder’s bill would also require those applying for a Class VI injection well permit, which are used for carbon storage, to submit an environmental analysis as part of the permit made to the conservation commissioner under the state Department of Natural Resources. This analysis would pose several questions about the proposed carbon capture project, summarized as:

- Have negative environmental effects been avoided as much as possible?

- Do the social and economic benefits of the project outweigh the environmental impact?

- Would other efforts offer more environmental protection than the proposed project without “unduly curtailing non-environmental benefits?”

- Are there other sites for the project that would offer more environmental protection without “unduly curtailing non-environmental benefits?”

- Are there measures that could alleviate the environmental impact of the project without “unduly curtailing non-environmental benefits?”

Local governments will also be notified.

The bill would also require local governments are notified when a permit is filed for a Class V or Class VI that would impact their parish. Those who own or operate Class VI wells would also have to provide quarterly reports to the conservation commissioner. This would include qualities — physical, chemical or otherwise — of the carbon dioxide stream that differ from what was proposed. It would also include monthly values and overall totals for the amount of carbon dioxide stored. The legislation also requires owners or operators make reports within 24 hours if the carbon dioxide stream or pressure endangers a drinking water source. This report would also have to be made if there was a malfunction that caused fluid to go in or near a drinking water source. Though there has been fierce opposition to carbon capture in Louisiana, the state is set to jump ahead with the technology. State lawmakers passed a resolution this session urging the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to grant Louisiana primary enforcement authority in administering permits for Class VI injection wells used in carbon sequestration.

is carbon capture the be all and end all or not?