Carbon capture is coming but where. Some areas are saying no and some legislators are proposing regulations. Regardless, the state wnts to control the permits.

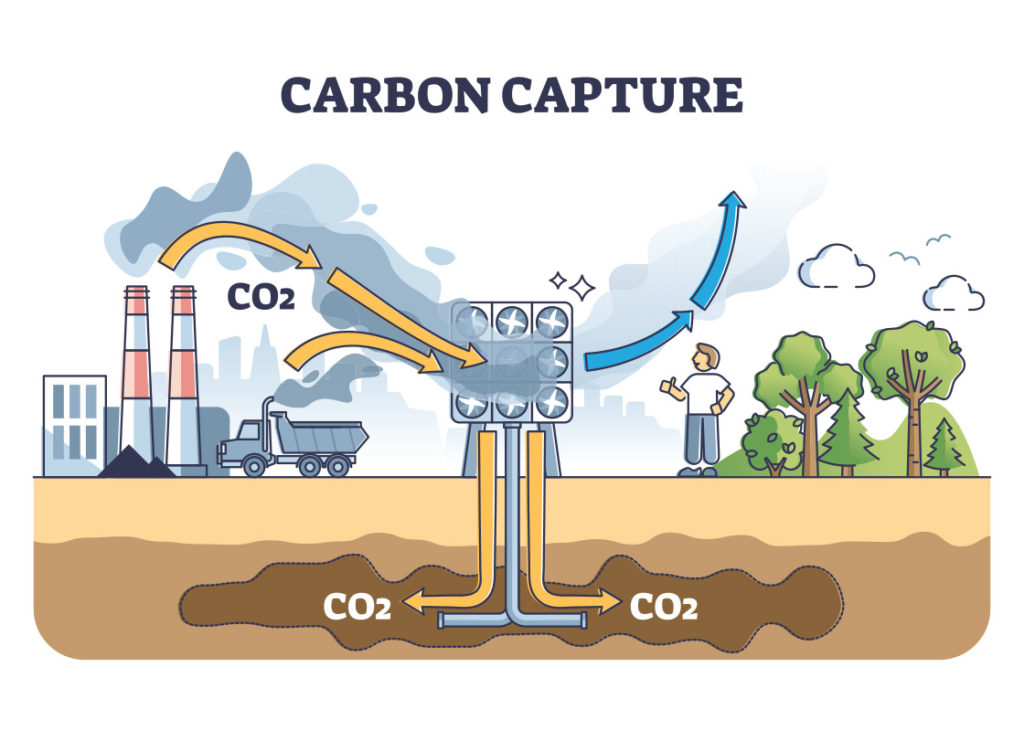

Carbon capture sequestration projects have drawn backlash from many people across Louisiana who fear the work will damage the environment and could lead to deadly accidents. At the same time, state officials — who tout carbon-capture as a new, environmentally friendly industry — are pressing ahead and hope the federal government will grant some autonomy in regulating the ventures. Carbon capture sequestration is championed by oil and gas companies, some environmentalists and many in the state and federal government as a way to control greenhouse gas emissions. Others have doubts about its effectiveness and argue the focus should be reducing emissions, not mitigating them. During carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), industrial plants divert the carbon dioxide they emit and pump it underground using injection wells. Louisiana is seeking the ability to permit and monitor the wells used in the capture process, a move Gov. John Bel Edwards says would help speed up such projects in Louisiana. Currently, only the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can grant permits for Class VI wells, the type used to inject carbon dioxide deep into the earth. Edwards and the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources last year applied for “primacy,” which means DNR would take over granting permits and monitoring wells. A recent letter from EPA Administrator Michael Regan to the governor said the federal government plans to complete a review of Louisiana’s request to take on oversight of carbon capture projects by May.

nola.com

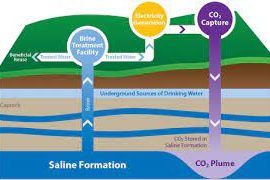

What is Class VI well

Class VI wells are used to inject carbon dioxide one to two miles into the earth for long-term storage. The Class VI requirements are designed to protect underground sources of drinking water and keep carbon dioxide from escaping into the air. The wells require extensive geologic testing and intense monitoring once they are approved. While the EPA permits Class VI wells as of now, the state DNR has authority over other types of injection wells. Those include Class IV wells, which are shallow and used for radioactive waste, and Class V wells, which handle non-hazardous fluids. EPA has issued six Class VI permits, all in Illinois. Two of those wells are currently active, and the other permits were issued for ones that were never constructed. Louisiana and other states say they could move the process along more quickly if they had the right to approve wells without the federal government. Only Wyoming and North Dakota have Class VI primacy, and both received it before the Biden administration took office. On average, the EPA has taken about three years to permit Class VI wells, but it took North Dakota only five months on its first well, as Louisiana DNR and others point out. As of March 24, the EPA had 49 pending applications for primacy from nine states. “EPA values and has considered the letters and stakeholder input received as we’ve been reviewing the Class VI UIC primacy application submitted by Louisiana,” the EPA said in an email.

There are conflicting views on state control.

Patrick Courreges, communications director for the Louisiana DNR, said his agency feels it’s better equipped to handle permits than the EPA for several reasons. “There are more requirements we have based on what we know about our state’s geology,” he said. “There are things that might be allowed in EPA that we will not allow. Things we will require that EPA doesn’t. We have more staff to dedicate to just this state than they would have, because EPA is working from Region Six, which covers five states. We have folks who understand our geology. We’ll have more staff per square mile dedicated to this state and its unique geology and our rules.” Others are less sure, citing past DNR failures such as Bayou Sorrel Superfund Site and abandoned wells in the Morganza Spillway. “I don’t think they’re going to do a good job,” said Iberville Parish Council Chairman Matthew Jewell, who represents the area where one carbon-capture project is proposed. “If history repeats itself, as it often does, they’re going to drop the ball. I would prefer the EPA to be in charge of it. I think they’ll do a better job than the state would.” Robert Verchick, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans and Tulane University who sits on Gov. Edwards’ Climate Initiative Task Force, is also skeptical, not only of the DNR’s ability to regulate wells, but of the Department of Environmental Quality’s ability to monitor them. “The EPA has a much better record than the state of Louisiana, that’s for sure,” he said.

The Administration has things they want included in the permits.

As part of its primacy consideration, the Biden administration is not only evaluating the ability of an agency to do the technical work of monitoring, but also requiring the state to have a plan for assessing environmental justice impacts, assuring that no group of people bears a disproportionate share of negative environmental consequences. Historically, studies show extractive industries have exacerbated health and economic inequalities. “The record on environmental justice from the DEQ and in the state in general has been very, very disappointing. In fact, there are recent lawsuits in which the DEQ has been found to have violated principles of environmental justice in its own assessments and permitting. So I think all of those things really add up to a lot of concern on the part of a lot of people,” Verchick said. DEQ Press Secretary Greg Langley said that new wells and pipelines would be the responsibility of the DNR, and that DEQ would only potentially be involved if carbon dioxide re-entered the atmosphere. “It’s new technology,” he said, adding that the agency’s role would become clearer if EPA grants Louisiana primacy.

The delays in granting permis may because of the newness of the technology.

One reason Verchick said the EPA could be taking so long to grant primacy to states is that CCS is very new. “There’s a lot that we don’t know about CCS, both in terms of how to keep the carbon under the ground for hundreds, thousands of years, which is something that’s never been done at scale anywhere in the world,” he said. “The second thing is that there are potential risks to doing that, which is what many of these communities are concerned about. I think that explains why the EPA seems to be taking its time on this issue, because they don’t want to get it wrong. The price is very high, and Louisiana would be one of the first.” Once the EPA completes its review, it will hold a 60-day public comment period, including the opportunity for a public hearing.

The states record is against them.