For the past 60 years, fertilizer manufacturer PCS Nitrogen and its predecessors have stored the phosphogypsum, the residue from their manufacturing, in a 180 tall mound. Chalky white, the material is nutrient loaded as well has having some radioactive elements and heavy metal residue. The company has been barred from dumping the residue into water but now, closing down the business, the company is asking permission to treat the material and dump it inot the Mississippi.

PCS Nitrogen and the state Department of Environmental Quality say the discharges would be held to federal drinking water quality standards and be quickly diluted in the vast flows of the Mississippi. “We are proud community members here in Louisiana and understand our responsibility to care for the environment and public health,” Richard Holder, general manager of the plant, said in a statement. “This water permit from LDEQ allows us to continue to fulfill that responsibility by facilitating our completion of closure and treatment of water from our permanently shut down phosphoric acid operations and associated gypsum stacks, which will benefit the environment and community in which we operate and our employees live.”

theadvocate.com

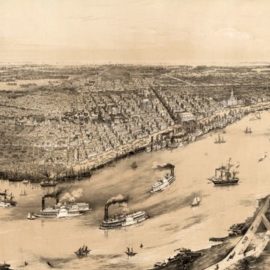

The Plan, which has had public hearings and a comment period has raised environmental questions as the Mississippi provides drinking water to a million people downstream including New Orleans. Many more depend on Bayou Lafourche for their water and Bayou Lafourche draws water from the Mississippi. There is a move to have the acid water declared a hazard waste. There is also the fear that the nutrient filled water will cause a larger dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Louisiana chapter of the Sierra Club and Healthy Gulf pointed to a June 2015 letter from the EPA to DEQ when the plant’s discharge permit was last renewed. The EPA noted concerns with the phosphorus standard, which imposes federal concentration limits but allows the amount of phosphorus sent into the river to rise as the river flow increases. The permit application in 2015 did not seem to address the impacts on drinking water systems downstream, the EPA added. “In the final permit and the current draft permit, these issues have not been adequately addressed,” Matt Rota and Naomi Yoder, two staffers with Healthy Gulf, and Darryl Malek-Wiley, of the Sierra Club wrote to DEQ in January of the latest permit.

As the company has phased down the fertilizer plant discharges have been reduced into the Mississippi. The Plan suggested will only reduce the concentrations a little and the company is proposing a quick clean up method.

The company wants to use a “double-lime treatment,” using quick lime to neutralize the water and cause contaminants to drop out in settling ponds before it goes into the river. The ponds, which are under construction along La. 30 and are expected to have their own air emissions, will eventually be permanently capped with the contaminants inside them.

No one is sure what the final contaminate reading will be, especially the radioactive elements, and this is a worry for Donaldson which has water intakes right below the discharge and then New Orleans which is farther down the river and noted that the current water tests do not test for uranium and radium for safe levels.

This is a bigger problem than just this one case. What’s to be done with acidic water when longtime waste piles like this one are headed toward permanent closure?

While a plant is still operational, the waste water is used and reused during phosphoric acid production to fuel creation of the acid and to deliver the waste gypsum in a wet slurry to the pile. The open air lakes collect rain in addition to the waste slurry, but the plants often use more water than the lakes store. Once production stops, however, a major of use of the water ends, and companies must find a way to get rid of the acid water to close the pile. If the water just sits in the storage lakes, they could collapse in Louisiana wet weather, causing an uncontrolled release of the acidic water.

There are other options which include trucking the waste away and deep well injection. The company says, however, these options cost too much and pose other risks. These are the problems that arise all the time and often have no good solution.