Some of my posts have been on the problems of the Mid-Barataria Diversion especially with oysters. A solution may be at hand!

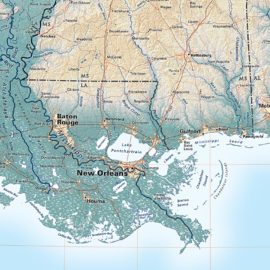

More rain and more flooding caused by climate change, along with plans to divert some of the Mississippi River’s flow, mean more freshwater is headed to Barataria Basin. That’s bad news for the oysters there, and for people fond of eating them. But a new LSU study says some oysters might do better than others. “Really productive oyster grounds right now are going to be exposed to a lot of really freshwater,” said Joanna Griffiths, an LSU alumna, marine biologist and the study’s lead author. “We want to know if those oysters can even tolerate it and how we might be able to further increase their tolerance.” The study’s findings suggests oyster hatcheries could breed bivalves with a greater chance of surviving those conditions. Found in brackish water, eastern oysters can withstand a wide range of salinities as adults. They grow best in waters ranging from 14 to 28 parts per thousand.

nola.com

To do the study, larvae were used as that is their most vulnerable stage.

The study focused on oysters as larvae, their most vulnerable stage, after growing the parents at a fresher Cocodrie site and a saltier area near Grand Isle. For two weeks, the microscopic larvae swim through the water column, with a premature shell that offers little protection from changing water conditions or predators, before permanently settling on a hard surface. Using the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries’ Grand Isle hatchery, Griffiths tried to raise larvae under two scenarios: Some in a more stressful environment with a salinity of 8 parts per thousand, others in the species’ preferred salinity of 15 ppt. Larvae that grew successfully in a lower salinity tended to share the same parents, suggesting the trait was innate to those oysters and passed down genetically. When larvae from the same parents was placed in the saltier baths, they grew even more rapidly. Where the oysters’ parents lived had little effect on larval growth rates. That might make selective breeding even easier if those oysters grow well in both environments, said Morgan Kelly, an assistant LSU professor of biology and Griffiths’ faculty adviser. “It could mean that if you pick oysters that are tough at those low salinities, they’re actually tough everywhere,” she said. “It could benefit them in both locations.”

The Department of Wildlife and Fisheries has only one of the two hatcheries in the state. They produce seed for those oyster men who raise them in cages. The studies work may give them a better idea of how to raise the seeds using the studies rationale.

“We’re hoping that this information about how to identify families that are tolerant of low salinities might help the hatchery choose the right parents to produce those seed oysters for oystermen,” Kelly said. Further study is needed, Griffiths said, to determine how those oysters would react to other factors such as warmer water temperatures. “It’s not just low salinity that they’re dealing with,” she said. “A lot of their tolerance may decrease if they have to deal with high temperatures at the same time.”

There will be at least 5 years before the waters will be changing giving even more time for studies like this one to make a big difference in the projected damage to the oysters and other marine life threatened.