NOAA/NMFS/SEFSC

Mandy Tumlin is a marine biologist that raised the question on what will happen to the bottlenosed dolphins when the Mid-Barataria Diversion is built. It is estimated that many will die. Was she fired because of this?

Some Gulf Coast researchers are raising alarms about a $2 billion Louisiana coastal restoration project’s potential to kill and injure bottlenose dolphins. Now, the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries employee whose job it was to count dolphin deaths in the state says she was fired because her work reaffirmed the project’s potential to devastate a dolphin population. Mandy Tumlin was the marine mammal stranding coordinator for the agency before she was fired in 2019. In that year, the Bonnet Carré Spillway was open for a total of 118 days to relieve pressure on the Mississippi River levees in New Orleans. It sent freshwater from the river into Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi Sound. A total of 337 dolphins were found on beaches along the Gulf Coast that year, and only nine of those survived, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Tumlin said it was “disappointing, and completely disheartening” to be fired while a large number of dolphins were dying from freshwater lesions due to the second opening of the spillway in 2019. “We feel that this was done so that the state of Louisiana can proceed with its plan to construct and operate the Mid-Barataria Bay and Breton Sound Diversion projects, which will actually be lethal on dolphin populations in those areas due to freshwater lesions and other impacts,” she said.

nola.com

Records show Tumlin missed deadlines. Did she? Were the reports correct?

Wildlife and Fisheries records say Tumlin was fired for missing a federal deadline to enter data into an online system about dolphin and sea turtle strandings. Tumlin’s attorney, Arthur Smith III, said the allegations are untrue. “The termination was a bogus, contrived setup,” he said. “Mandy made all deadlines for which she was responsible.” Tumlin began working for the department in 2005. She responded to marine mammal strandings during the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in 2010, saving hundreds of sea turtles. “I gave my life to this. I missed out on celebrations and holidays,” she said. “My personal cell phone was the statewide hotline for marine mammal strandings. I was on call constantly.” When the 2019 openings of the Bonnet Carré Spillway were blamed for dolphin deaths, she said, she was not given permission to talk to reporters about the issue. “When media requests came in, I had to toe the line as a state employee,” she said. “It felt like there was just this constant roadblock.” However, when reporters had made previous requests for information about sperm whale strandings in 2017, she was allowed to do interviews.

George Ricks, a major opponent of the diversion, is one who said he could get answers from Tumlin.

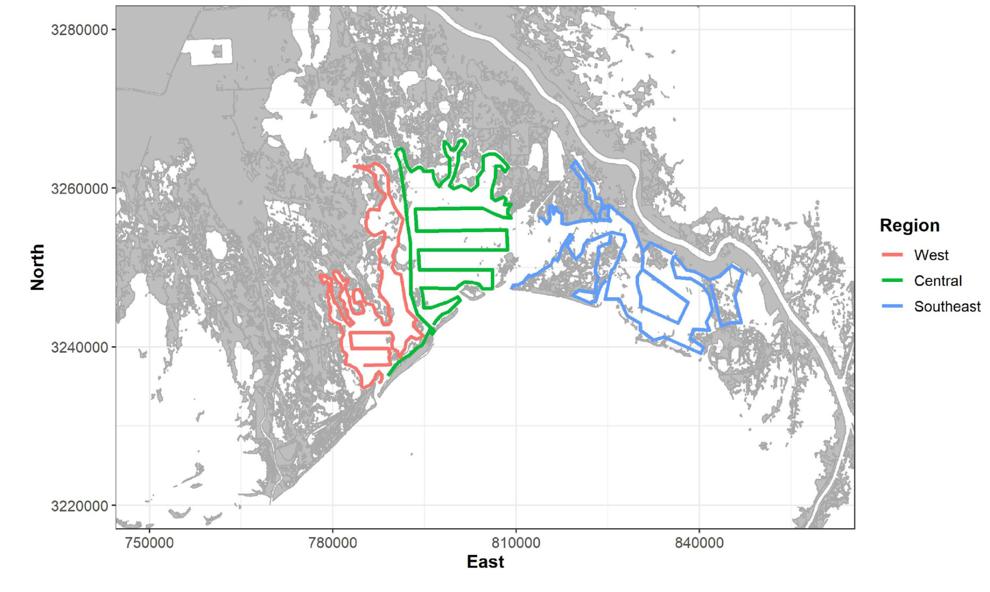

Among those who felt they weren’t able to get information out of Tumlin while she was employed was George Ricks. He’s a vocal opponent of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, designed to create a controlled opening in the Mississippi River’s West Bank levee below New Orleans and flush river water into Barataria Bay in an effort to rebuild wetlands with river sediment. The project would allow freshwater to pass through the levee for longer duration’s than the spillway was opened in 2019, which could lead to more dolphin fatalities. “There were a couple times I asked her in texts, ‘Is river water what’s killing these dolphins?’ She never would say,” Ricks said. Ricks testified in one of three meetings that Louisiana State Civil Service held after Tumlin appealed her dismissal in 2020. “They put me under oath and asked me if there was any reason that I saw that she should have been terminated. I said no,” Ricks recounted.

National Marine Fisheries Service biologists. National Marine Fisheries Service

Tumlin will hear her fate in the next few months.

A federal draft environmental impact study released in March for the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project acknowledges its potential to have “immediate and permanent major adverse impacts” on the bottlenose dolphin population in Barataria Bay. A study requested by the Marine Mammal Commission and submitted in May found that the diversion would result in “functional extinction” of dolphin populations in two areas of Barataria Bay. The study attributed the deaths to prolonged exposure to freshwater, which causes burn-like lesions on dolphins. “Freshwater lesions will make them more susceptible to viral infections that will cause mortality,” Tumlin said. “Their skin turns into what looks like a Brillo pad.” Tumlin said she was not given adequate resources to do her work responding to calls about marine mammal strandings, including dolphins.

Tumlin was not replaced but her responsibilities were given to the Audubon Nature Institute .

In Tumlin’s absence, Moby Solangi, executive director of the Institute for Marine Mammal Studies, grew concerned that marine mammal deaths were not fully counted in the transition to Audubon taking over. “I know there’s some controversy about it,” he said. “A large amount of animals were not recovered because of this sudden change.” More than 150 of the dolphins found dead in 2019 turned up in Mississippi, where Solangi is based. He blames the spillway opening for the dolphin deaths, as well as for oyster, blue crab and shrimp fatalities. More than 50% of the stranded dolphins in Mississippi had sores on their body from low salinity, he said. “These animals cannot just swim away,” Solangi said. “By the time they realize things are bad, they are sick and die.” Dolphins have a very strong affinity to the areas where they live and are unlikely to move away when their environment becomes inhospitable, Solangi said. “It’s like saying every time there’s a hurricane people from Louisiana should move,” he said.

Marine Mammal Commission/Alissa Deming, Dauphin Island Sea Lab

It seems strange that the same opponent testified three times. Did some one on the board have a grudge against her? Was she a “whistleblower” and punished for that? Many questions remain.