Gordon Park. A toxic landfill where people live. Maybe not much longer.

Shortly before Congress approved the federal infrastructure law, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell touted the $1.2 trillion package as key to buying out Gordon Plaza residents who had learned, only years after moving into their homes, that the subdivision was built atop a toxic landfill. “It speaks to our ability to really look at environmental injustices that our folks have had to live with like Gordon Plaza,” Cantrell said of the infrastructure law in an Oct. 21 interview with WBOK radio. “It creates an opportunity to tap into resources to build a solar power farm and then have revenue to potentially move our people off of that land.” Her words were bolstered Nov. 4 when her chief administrative officer, Gilbert Montaño, told the City Council there was a “general line item” in the administration’s 2022 budget proposal dedicated to moving forward on buyouts, using money borrowed through a $300 million bond sale. “I know that there’s various pieces of litigation associated with that, but I wouldn’t let that stop us from trying to move forward and continue to make it a priority at the mayor’s direction and ensuring that this gets resolved within this bond package,” Montaño said. “There is a specific line item within our capital budget that will begin as a starting point for us to then decide once … calculation methodologies come to fruition to build up in some sort of way to rectify the situation.” “This is imminent,” he said. “This is something we will figure out.”

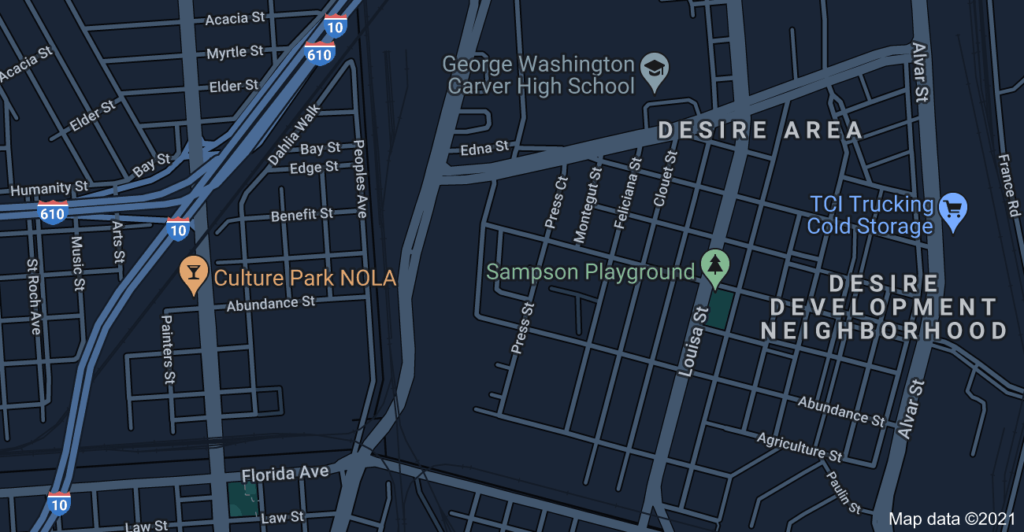

nola.com

This is music to the ears of the residents. It may be the end of a long push for equity.

For some Gordon Plaza residents, his words represented a breakthrough moment, the first time City Hall said money was allocated to their cause. But as of Friday, the Cantrell administration’s published budget proposal contained no mention of Gordon Plaza, let alone a dollar figure, and a timeline for their relocation is still unclear. “We appreciate the words, but what we need more than ever is an urgent — and we mean urgent — commitment to follow through in action toward resolve,” said Jesse Perkins, a member of the four-person governing board of the nonprofit Residents of Gordon Plaza Inc.

What is Gordon Plaza and how did we get to this state?

Constructed atop the 95-acre site of the Agriculture Street Landfill in 1981, the Gordon Plaza subdivision was billed as a move to expand affordable housing options in New Orleans and marketed toward Black residents looking to buy homes. What they didn’t know was that the soil beneath their feet was laced with more than 50 hazardous compounds such as arsenic and lead caused by five decades of waste disposal there. In 1994, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared Gordon Plaza one of the most contaminated Superfund sites in the country, mobilizing a cleanup effort that excavated and removed almost 70,000 tons of material and replacing it with a 2-foot layer of clean soil. In its latest five-year review, released in 2018, the EPA found that its actions were “protective of human health.” But in 2019, a report from the Louisiana Tumor Registry found that the Desire neighborhood, which includes Gordon Plaza, has the second-highest consistent rate of cancer in the state. Residents blame the landfill. Two reports commissioned by the Tulane University Environmental Law Center, which represents the residents in court, concluded that they are likely subject to elevated health risks due to their location but that more sampling is needed to understand the extent of the risk.

The city has plans for the area that will not involve residents. I will be part of the greening of the city. Yet if the area is so polluted, should it not be cleaned up?

The Cantrell administration’s pledge to help residents comes as it looks to redevelop the site, potentially as a renewable energy park to power Sewerage and Water Board pumps. In July, an EPA feasibility study concluded that portions of the Superfund site would be appropriate to reuse as a solar farm. That study found that 40 publicly owned acres west and south of the subdivision could support solar. Ramsey Green, Cantrell’s deputy chief administrative officer and chief resilience officer, said Thursday that Montaño, in his comments to the City Council, was likely referring to about $2 million from the bond sale to hire a company to conduct more analysis, not buy people out. That’s about 6% of the $34 million that Gordon Plaza residents say they need for buyouts and moving expenses. “We’ve done a lot of due diligence on this on the front end, but there are steps to initiate the process of relocation,” Green said. “There has to be analytics to figure out the costs and that kind of stuff, and that requires a professional firm to help us through that process.” Buyouts are a much bigger step. That’s where the federal infrastructure law comes in. It gives the EPA $5 billion to clean up Superfund sites and revitalize brownfields. On Thursday, Gordon Plaza residents met with EPA Administrator Michael Regan, who committed his agency to partnering with them to solve the problem. “That’s a bigger financial commitment,” Green said. “I think the city and the mayor have made it very clear how big of a priority this is, based upon the EPA administrator’s visit. I mean, that wasn’t by accident.”

Money is always the problem and is it ready to spend? No.

But the details of how the federal money may be used are not yet known. Wherever the money comes from, Perkins said, residents just want city officials to follow through on their word and to ensure that residents who wish to leave are moved out before any redevelopment begins. He said he feels cautiously optimistic after Regan’s visit. “I don’t want to die fighting this stuff,” he said. “But now I think I’ll live to see the benefit.”

Is the end in sight? I hope so as the residents are in danger, a silent danger, but a real danger.