the 2020 Census shows that the bulk of the population of Louisiana is in the bottom third. The area with deltas and where we are osing and daily. No, they are no living in a Cajun cabin like this but the land may be the same. People living in danger.

Growing up, Virginia native Michael Dameron spent every summer in south Vermilion Parish with his father and grandfather fishing for pogy, splitting his time between the East and Gulf coasts. He was no stranger to hurricane season. “This was like a second home to me,” Dameron said as he stood outside his house on a recent day, leaning against his hunting buggy and running down the list of storms he’d ridden out in Louisiana. Twenty-five years ago, the fourth-generation menhaden ship captain and his wife decided to pack up and move full-time to Abbeville, just 15 miles north of Vermilion Bay. But over the years, the storms seem to have worsened, Dameron said, and the catastrophic flooding of 2016 was the final straw for him. “Down here, you want to get as far north from Highway 14 as you can,” he said, referring to the state highway paralleling the coast from New Iberia through Abbeville to Lake Charles. South of that line, some residents have difficulty securing flood insurance. So in 2017, the Damerons bought a house in the village of Maurice, about 10 miles farther inland, in the heart of sugar cane country. For him, it was in a Goldilocks zone: far enough from the water to ditch the mandatory flood insurance, but close enough to still work and play along the coast.

nola.com

He constantly moved north but not our of the danger zone.

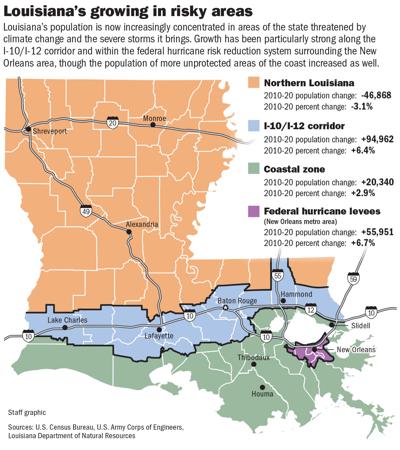

And he wasn’t alone. From 2010 to 2020, Maurice more than doubled in size, jumping from 964 residents to 2,100, making it the state’s fastest-growing municipality. The nearby city of Youngsville experienced a similar boom, jumping from about 8,200 residents to nearly 16,000. The new development has been a boon for these communities. But the growth of Maurice and other Lafayette suburbs offers a peek at an increasingly urgent dilemma for Louisiana: The state’s fastest-growing areas are concentrated in the same regions that will be most at risk from climate change in the years to come. According to the latest census, nearly 3.2 million people lived along or below the Interstate 10 corridor in 2020. That’s over two-thirds of the state’s population in just one-third of its area. The southern part of the state now has 200,000 more people than it did when Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. Even as people continued to flock to more vulnerable parts of the state, the relatively safe parishes to the north shrank by nearly 47,000 in the last decade. That diaspora is part of a national trend that has seen rural areas around the U.S. dwindle.

In the example, Lafayette area grows as is he New Orleans area. Both are below I-10. The upper two thirds is losing population and towns are disappearing.

The growth in Louisiana’s south over the last decade has been driven by a number of factors: The presence of industry and jobs, which often means being near the refineries along the Mississippi River and the oil rigs in the Gulf; national trends that have seen people gravitate more toward urban areas, which are scarce above the toe of the boot; and the continuing trickle of people returning to the New Orleans area after being dispersed by Katrina. Now, more than 2 out of every 3 Louisianans reside in south Louisiana, where already severe floods and storms are expected to steadily worsen as the planet warms and more of the state’s coastline washes into the Gulf of Mexico. There are signs that the risks aren’t lost on residents. The growth in the southern parishes isn’t uniformly distributed. Areas closest to the Gulf have seen their populations drop over the past 20 years. For example, in Vermilion, areas north of Kaplan and Abbeville, in the Lafayette suburbs near Maurice, are rapidly expanding, growing by about 11% over the last decade. But the southern parts of the parish are nearly a mirror opposite: they lost 9% of their residents as folks like Dameron tire of rebuilding.

The better the levee system the more people who live withing it.

Around New Orleans, nearly all of the growth south of Lake Pontchartrain has occurred in areas protected by the $14 billion federal levee system built after Katrina. Still, Justin Kozak, a project manager for the Center for Planning Excellence in Baton Rouge, doubts most people have a complete picture of the risk that comes with living south of I-10. Historically, not even flood insurance premiums have accurately reflected a property’s risk, and they’re often based on maps that can be more than 20 years old. “It’s not well communicated. Even when it is, people discount it,” Kozak said. “I just don’t think people are getting the feedback and are making a decision on where to go without it.”

The threats are real and we see them after every storm.

The recent past has shown the threats are not just theoretical, and that they pose risks to areas not directly adjacent to the coast. The 2020 census count put Calcasieu Parish’s population at nearly 217,000 after a decade of rapid expansion that swelled its numbers by 13%, the fifth-fastest rate in Louisiana. With that count, Calcasieu surpassed Caddo Parish — home to Shreveport — as the sixth-largest parish in the state. At the same time, Caddo saw its population shrink by 7%. But then Hurricane Laura struck, bringing massive devastation and flooding to the Lake Charles area that was, followed by Hurricane Delta six weeks later. It was part of an unprecedented season that saw named storms strike the state’s shores five times. A year later, Hurricane Ida ravaged Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes, which had seen 6% growth over the prior two decades. It remains to be seen what those disasters will mean over the long term for any of those parishes, or for similarly hard-hit areas such as Lafitte and Grand Isle in lower Jefferson Parish. But it’s likely that the rebound will be slow: it took New Orleans 15 years after Katrina to return to just 80% of its pre-storm population.

Even with the growth below I-10, there seems to some thought on what to do if you live in danger.

There are signs that even as south Louisiana grows, the new residents may be seeking to balance the threats they might face. South Louisiana can be split into two parts: the coastal zone, a state-defined designation starting at the Gulf that includes both small communities and large parishes such as New Orleans and Jefferson; and the areas north of it, such as Baton Rouge and Lafayette. At the start of the millennium, the majority of residents in the south lived inside the coastal zone: 1.7 million people, compared to 1.3 million just to the north. That population gap has narrowed significantly. The coastal zone lost 61,000 residents over the past 20 years, in large part due to Hurricane Katrina, while the region just to the north gained 264,600. Of course, being outside the coastal zone is no guarantee of protection, as the 2016 floods proved. After originating in the Gulf, a slow-moving line of storms dumped more than 20 inches of rain over three days and inundated 21 parishes. The floods — which the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration directly linked to climate change — devastated areas like Youngsville and left Maurice residents trapped in their homes. Soon after the 2016 floods, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration found that human-caused climate change had made the August storms at least 40% more likely to occur.

As with many places, the appearance gives a false sense of security.

Vermilion native Ashlynn Broussard, a Farm Bureau insurance agent, bought a house in Maurice in 2019, both for work and to take advantage of its excellent schools and low cost of living. She’s fallen in love with the small town, filled with familiar faces. Now, she’s building her second home there, and she’s sparing no expense to fortify it against the storms that will likely come, from a metal roof to elevation. Nor is she passing on flood insurance, and she advises each of her clients to buy it as well. “The risk is minimal here compared to some of the other places in the parish,” she said. “But we still need to remain cautious because the coastline’s eroding. I’m leery of a false sense of security.” Growth seems unlikely to stop anytime soon in areas around Lafayette or New Orleans. But to ensure sustainability, Kozak, the urban planner, said communities must recognize that all new development changes the landscape. That in turn changes the area’s relationship with water at both a local and watershed level. “If we want to maintain population, if we want to maintain safe housing stock and if we want to avoid the uncertainties of the long-term costs of flood insurance,” he said, “we should build in a way that maintains that property value and maintains these communities so that we can have some longevity to them.”

Flooding is an eyeopener and that is when you need to make a better assessment.

That fact isn’t lost on Youngsville officials, Police Chief Rickey Boudreaux said. After new recreational facilities and low crime rates brought rapid growth, the 2016 floods served as “an eye-opener.” “We don’t want to have another 2016. It brought all the things that we knew were there but brought them to the forefront,” he said. “As you build subdivisions, that takes away the cornfields, that takes away absorption.” The city has since purchased 12 properties that will serve as retention ponds to help with drainage, while doubling as dog parks, fishing piers or other public facilities. Officials have also raised building standards, and developers of new neighborhoods must now construct their own retention ponds. Within the global problem of climate change, Kozak noted that one of the few things that growing localities can control is how and where development occurs to limit risk. Some models attribute most future damage to building in higher-risk areas. “Only a third of it is going to be because of climate change,” Kozak said. Climate change is “certainly not helping, but we have it in our capacity to manage this development pattern and population movement. But we’ve already built ourselves into a tough situation, and it takes a long time to build yourself out of it.”

We see that here with the land needed for better levees. We buy flood insurance. We take precautions even if it is determining where we flee to!