The EPA will be doing surprise air monitoring tests in Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi. We asked for them and they provided.

Focusing on environmental justice in Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency plans start unannounced inspections of industrial polluters, install more fenceline monitors at the plants and push state and local officials to step up their own enforcement. “I asked my team to go further and faster than we’ve ever done before to elevate protection for people who have historically been left behind in underserved communities,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said Tuesday. “Those who are suffering disproportionately under the weight of the pandemic, who are on the frontlines of climate change, who suffer more from pollution, have been waiting long enough. And they are counting on us to get this right.” Regan announced the initiative two months after his Journey to Justice Tour of minority and low-income communities in the three states.

nola.com

These are the steps the EPA will do in the monitoring:

Among the broad steps the agency will take are: Conducting unannounced inspections of “suspected non-compliant facilities” and, when they are found to be violating their emissions permits, using “all available tools to hold them accountable”, Creating a Pollution Accountability Team that will use EPA’s air-monitoring ASPECT airplane, a mobile air monitoring vehicle and a team of air pollution inspectors to enhance enforcement, Distributing $20 million in American Rescue Plan grants to invest in new community air monitoring stations in areas thought to be vulnerable to high levels of air pollution. It’s the largest investment in air monitoring in the agency’s history, Holding companies more accountable for their actions in communities with high pollution levels, by increasing monitoring and oversight of their plants and Applying the best available science for policymaking decisions, such as a proposed screening methodology announced last week to evaluate chemical risk in fenceline communities.

Regan noted the usefulness of the meeting he had with residents in his recent visit.

Regan said his meetings with many residents during tours of communities in St. John the Baptist Parish and St. James Parish, in what critics call Cancer Alley along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, and in Mossville, in Calcasieu Parish near Lake Charles, helped him understand the effects of pollution, climate change and crumbling water infrastructure, all of which are targeted by the new programs he announced. The Pollution Accountability Team will conduct pilot air monitoring programs in all three communities, he said. “EPA will work with residents and community leaders to determine the routes to be traveled by the mobile monitoring vehicle and the contaminants to be monitored,” EPA said. The agency’s Region 6 office in Dallas will make the data collected available to the public. EPA also will spend more than $600,000 for new mobile air pollution monitoring equipment to be deployed in all three locations, and in other communities in the South. The monitors will measure volatile organic compounds, including air toxics, and EPA will work with local groups to train community members on how the technology works and how EPA uses the results.

Letters have already been sent to some of the industries involved.

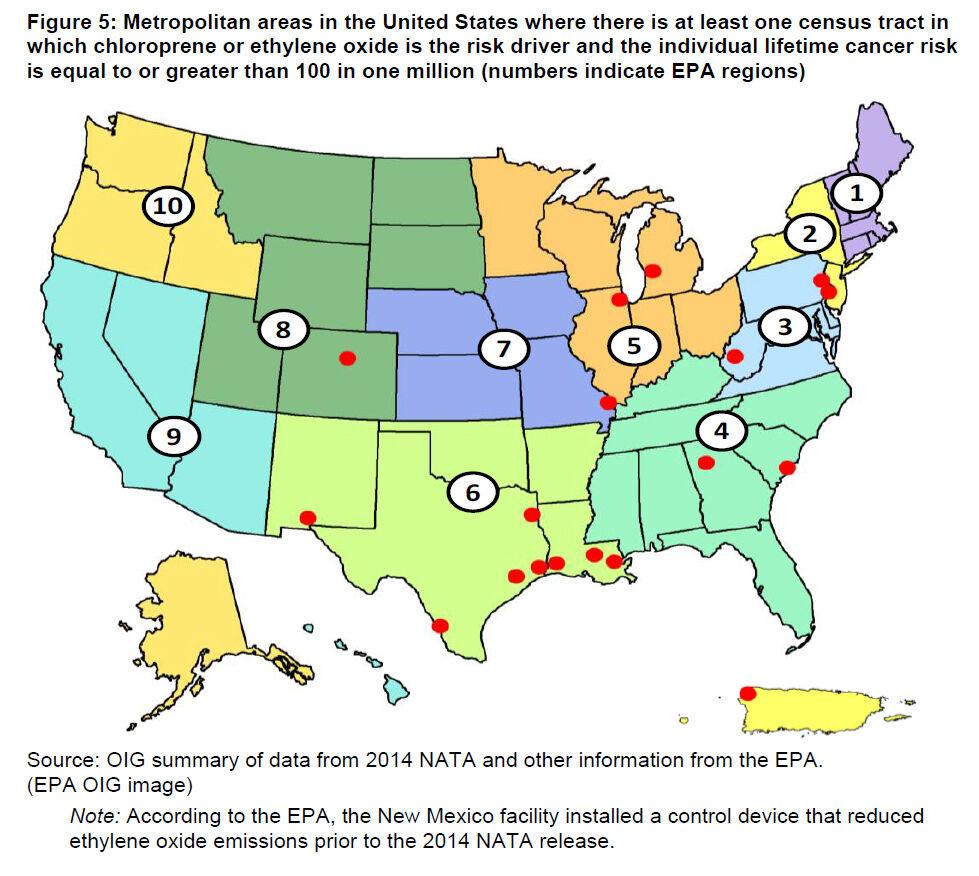

In St. John, Regan said he’s already sent letters to Denka Performance Elastomers, owner of a controversial Reserve manufacturing plant that manufactures chloroprene, and DuPont, the former owner of the plant, raising concerns about its continued emissions and their effects on the nearby Fifth Ward Elementary School. And he said he’s working with the Justice Department to identify other ways to reduce the plant’s emissions. “In St. John the Baptist Parish, there are more than 500 elementary school children who attend school right next door to a chemical plant that manufactures chloroprene,” Regan said. “As a parent, I am extremely concerned about the potential pollution these children breathe every day.” “I am writing to you today to reiterate what I hope are our shared concerns and expectations over the health and well-being of the students,” Regan wrote in the letters. “EPA expects DuPont and Denka to take other needed action to address community concerns.”

Regan also took aim at the Formosa plant, joining many who have done the same.

Regan also targeted the proposed Formosa Plastics plant in St. James Parish, pointing out that EPA supported the Army Corps of Engineers decision last August to conduct a “more robust” environmental impact study of the plant. The agency will offer technical support as the Corps adds key segments to the original environmental statement, including an evaluation of reasonable alternatives of the expansion proposal, the potential cumulative effects of emissions from the proposed plant and those from other plants in the area and the inclusion of a public comment period, which was not required before the Corps issued its first report. Citing an example of the agency’s stepped-up enforcement, Regan also announced that EPA issued a notice of violation on Monday to Nucor Steel Louisiana’s direct reduced iron plant, also located in St. James. It requires the company to address unauthorized emissions of hydrogen sulfide and sulfuric acid mist, and its exceedance of permitted limits for sulfur dioxide emissions. Regan also announced that EPA will speed up its review of the Gordon Plaza neighborhood in New Orleans, beginning in March and including nine more houses than had been included in previous reviews.

The agency also stated the reasons they are taking action.

“The agency is taking this step to re-evaluate its previous decision that the land is safe and to communicate the results to the community,” the agency said. Regan met with New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell and Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, on Jan. 6, to discuss relief for residents living atop the city’s old Agriculture Street Landfill. “The solutions discussed would support relocation of community members off the land, provide economic opportunity for the city, advance clean energy and lower greenhouse gas emissions in the area,” the agency said, without explaining those alternatives.

Mossville was also discussed.

In Mossville, EPA is focusing on the $13 billion Sasol Chemicals USA LLC plant, Regan said, including a notice issued this week of potential violation of federal risk management rules, discovered during a January 2021 compliance evaluation. Mossville is one of the locations where EPA on Monday announced it would significantly increase the number of inspections, to determine whether they prevent potentially elevated risks to neighboring communities. The inspections are based in part on recent EPA helicopter flyovers and mobile air monitoring in the area. EPA also announced that it has given $38,886 to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality to buy a continuous monitor to track emissions of particulate matter 2.5. It will be placed across the street from the Sasol’s Lake Charles complex.

Regan discussed the drinking water problems in Mississippi and pollution in Texas.

Regan also focused on drinking water problems in Jackson, Miss., describing how, on the day his tour was supposed to visit the Wilkins Elementary School, the school day was canceled because of low water pressure. The same water treatment plant serving the school broke down this week in cold weather, he said, resulting in boil water advisories being issued for much of the city. “Today, EPA issued a notice of noncompliance to the city for failing to repair and maintain equipment necessary to reliably produce drinking water,” he said, adding that he’s sending a letter reminding Jackson elected officials that the state has $79 billion in federal infrastructure funds available for water system repairs. In Texas, as in Louisiana, EPA’s beefed up enforcement will target plants manufacturing ethylene oxide. Regan said the agency on Tuesday reaffirmed a peer-reviewed scientific assessment that indicates the chemical is “significantly more toxic than previously understood.” As a result, he said, EPA is rejecting an attempt by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to set a less protective risk value for the chemical, which would allow more of it to be released from factories in the state. That same opinion will be used in determining the amount of ethylene oxide allowed to be released at plants in Louisiana, such as the proposed Formosa Plastics plant.

The EPA is far more responsive than in the past and Regan is one who does listen to people, the people not the industry.