The Governor gathered representatives of all stakeholders in his Climate team and they came up with resolutions on what the state needs to both have a good economy and stem the ill effects of climate change. Will these ideas and recommended actions survive the approval system in the state legislature?

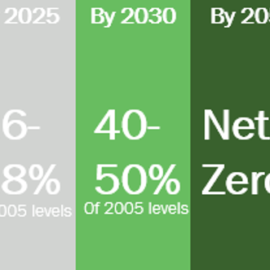

The climate task force created by Gov. John Bel Edwards, the Deep South’s only Democratic governor, brought together people from across a broad ideological spectrum, from petrochemical executives to environmental advocates to urban planners. They spent months crafting a document that sketches out how Louisiana can reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, hopefully doing its part to avoid climate catastrophe while keeping the state’s creaky oil-reliant economy relevant as the world shifts to renewables. If putting together the document was hard, following through will be much harder.

theadvocate.com

A democratic governor with a republican legislature. One accepts climate change and sees needed actions the other does not accept climate change and maintains we are an oil state. Climate change is real and we are no longer an oil state.

Edwards will leave office due to term limits in 2024, and it’s widely expected that a Republican will replace him. Parts of the plan will require unknown amounts of money, not to mention buy-in from a conservative Legislature that historically favors the oil and gas industry. And even within the task force itself, there are disagreements over a key aspect of the plan: how to decarbonize Louisiana’s industrial sector, which emits an abnormally large share of the state’s greenhouse gases. It’s also unclear whether Edwards’ successor will pick up the net-zero torch. Attorney General Jeff Landry, considered a likely candidate for governor, appears dead set against it. Following the lead of Republicans in other states, he recently demanded that Treasurer John Schroder, a fellow Republican who recently announced he’s running for governor in 2023, divest the state from BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, partly because BlackRock has embraced net zero goals. (Landry’s most recent financial disclosures show that he personally invests in BlackRock, though a spokesperson said Landry took his own money out “many months ago.”)

This is one person, but the republicans in the house and senate feel the same way.

Whether the Legislature and Public Service Commission, both dominated by the GOP, will embrace the recommendations of the task force also remains to be seen. House Speaker Clay Schexnayder’s designee to Edwards’ task force is a petrochemical executive, and Schexnayder himself last year sponsored a resolution on behalf of the farming industry asking Edwards’ administration to halt certain incentives for utility-scale solar projects. The Legislature also axed a generous tax-credit program for rooftop solar a few years ago amid a budget crisis. The Public Service Commission, which regulates power companies, has for years resisted calls to mandate that power companies get a certain share of their power from renewables. Advocates for cleaner energy are hopeful that stance will change since wind and solar have gotten cheaper to produce. ‘I think it’s a big challenge,” Rob Verchick, a law professor at Loyola and a member of the task force, said of the political headwinds the plan faces in Louisiana. ”And it’s actually something that a lot of states deal with, not just ours. But obviously as an oil-and-gas state, we have some powerful forces that in some ways probably want to keep things the way they are.”

There is hope, though as maybe the tide is turning.

Still, net-zero proponents remain optimistic that the tide is turning here. Edwards said he’s not ”naive” about the challenges. But he said the energy sector is changing, and that the plan will start bringing jobs and investment that will be hard for state leaders to turn away from. ”It is my hope, it’s my expectation, that we move this far enough down the field, that nobody who comes behind me, regardless of what their philosophy is today, would think it’s a good idea to move away from that,” Edwards said. ‘If you don’t have it all figured out, does that mean you don’t take the first step forward? I think that that is pure folly,” he added. Many task force recommendations need approval by the Legislature to become law. Neither Schexnayder nor Senate President Page Cortez, who each named people to the task force, returned messages seeking comment. Cortez’s designee to the task force is Timothy Hardy, a former state environmental regulator who now helps companies navigate environmental rules as an attorney. State Sen. Sharon Hewitt, a Slidell Republican who worked for Shell as an engineer on deepwater drilling rigs for years, brought legislation last year aimed at encouraging a practice called carbon capture, which allows industrial plants to store CO2 underground instead of emitting it. The technology is controversial and has revealed disagreements among Edwards’ climate task force members over its efficacy. But the governor has leaned into the technology as a way Louisiana can keep its industrial sector alive while also decarbonizing. Hewitt said she’s interested in joining the debate over the task force’s recommendations in the Legislature. She said she believes industry can develop solutions to decarbonize. ”We can’t just say we’re protecting the environment at all costs,” she said. ”There has to be a business component to it.” ”It’s a balancing act,” Hewitt added. ”I think we definitely all want to be more environmentally responsible and to be better stewards of the environment and to create less carbon in the atmosphere. How fast you can do it and (costs) have to be factors in how we can implement a plan to do that.”

There are others who have questioned many of the renewable energy projects.

Senate President Pro Tem Beth Mizell, R-Franklinton, helped lead the charge last year in questioning whether utility-scale solar projects in rural areas like hers were being built irresponsibly. Mizell said she’s not against solar generally, but wants to ensure solar developments aren’t taking prime real estate away from farmers who lease their land, among other things. Such concerns are among the hurdles faced by state officials and developers in building the infrastructure – including solar projects and transmission lines – the task force says will be needed to get to net zero. ” tI hink we’re in a hurry to get somewhere; at what price?” Mizell said. ”These are not decisions to be made quickly, for a goal on energy accomplishments. The welfare of the relationships of the people of the community is at stake right now.” Mizell said she hasn’t yet read the task force report, but that it would be difficult for her to support moving away from oil and gas entirely. She said her son works in the energy industry in Texas.

The question is what will Louisiana represent to companies considering a move here.

Camille Manning-Broome, president and CEO of the Center for Planning Excellence, said Louisiana’s risks from climate change are so serious that they ”will make it hard for any future governor to deny the need to act” on climate change. Still, when her organization hosted a workshop with Edwards and his cabinet in 2018, participants saw political realities as the biggest barrier standing in the way of Louisiana’s climate goals, Manning-Broome said. She was among several task force members to formally oppose recommendations embracing carbon capture and sequestration – the preferred carbon-reduction strategies of the petrochemical sector. ”If we choose to continue to invest in political divisions at the expense of timely, datadriven climate action, the viability of this state is very much at stake,” Manning-Broome said. ”I also see it as the role of the task force to present these realities to the public, so that they have the power of knowledge to choose to reject divisive political messaging that holds Louisiana back.”

The demand for oil is shifting to lower needs and we can’t stay as an “oil state”.

Several proponents of the plan warned Louisiana’s economy is perhaps as much at risk from climate change as its ailing coastline, given the worldwide shift away from the fossil fuels that dominate Louisiana’s manufacturing industry. Broderick Bagert, an organizer with Together Louisiana, likened the risk Louisiana faces to that of Blockbuster, the retailer that went belly-up after streaming platforms took over the video industry. ”It wasn’t dew-eyed liberals who positioned Texas as the No. 1 provider of (wind energy) in the country,” he said. ”It was businesspeople who understood the realities of the energy transition.” To that end, Bagert is optimistic that the economics of wind and solar can help drive the greening of Louisiana’s electric grid. He also hopes places like New Orleans can take action and show the rest of the state that decarbonizing is good for the economy.

Emissions and what to do with them is maybe the biggest question.

As the report has come into sharper focus – the final version will be publicly unveiled and voted on Monday – so have the disagreements among people involved in its creation. Industry groups and Edwards have touted carbon capture as a crucial part of the plan. Industry representatives on the task force say it’s the best way for carbonintensive manufacturers to reduce emissions. ”As the governor and his staff have mentioned, Louisiana’s future is carbon capture, hydrogen, natural gas, and reducing emissions of liquid fuels through market-driven solutions,” said Tommy Faucheux, president of the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association. ”Louisiana has long been a leader in energy production. Now is the time for Louisiana to lead in the energy transition.” Verchick, of Loyola, who co-authored a report in December that described carbon capture and sequestration as a ”false promise,” disagrees with that aspect of the plan. He laid out a host of reasons Louisiana should push instead for electrification of industrial processes and investing in technology that allows feedstocks like ammonia to be produced without fossil fuels. He noted Louisiana’s largest single emitter of carbon is an ammonia plant in Donaldsonville owned by CF Industries. Verchick argues carbon capture and sequestration is unproven, poses environmental and health risks and requires the building of invasive new pipelines in wetlands. He called Louisiana’s embrace of the technology a ”mistake.” ”It’s hazardous, it’s unproven. … It’s a waste, frankly, of taxpayer money,” he said.

Not all of the plan is being questions but those that are have a lot of questions.

Harry Vorhoff, who heads up climate initiatives for Edwards, noted that the majority of the plan got unanimous support. But it’s the section dealing with industry that is most contentious. Louisiana is the only state where industry produces more than half of the state’s carbon emissions. Industry in Louisiana actually accounts for 66%. And it’s considered much more challenging to eliminate industrial emissions than to clean up the power grid and replace gas-guzzling cars. The discord on the task force becomes evident at the end of its 178-page report, which contains a list of 48 ”dissents.” There, members expressed ”grave concern” about one component of the plan or another. While several members formally opposed things like carbon capture and ”lowcarbon” hydrogen production, another controversial technology, industry groups had a different set of problems. The Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association and the Louisiana Chemical Association opposed recommendations to get government regulators involved in the effort to get to net zero, saying instead the state should rely on ”market forces” to drive the shift. Greg Bowser, head of the Louisiana Chemical Association, said he thinks some of the recommendations will be implemented – namely carbon capture. He said the state should let the available technology determine when it reaches net-zero. ”Our concern is Louisiana may shift to some of this, and what happens if some other states in the region don’t do the same?” Bowser said. ”We could wreck our economy and no one else does it. The projects and businesses we shut down here simply move to Texas.”

Is the shift now happening? Will the force of changes that have been done force the issue?

Advocates counter that the transition is already happening, and that mandates can help make sure Louisiana isn’t mired in irrelevance by the time fossil fuel sectors dry up. For instance, Shell and BP are among the oil majors with net zero goals, and Louisiana is expected to become a player in the offshore wind boom predicted in the Gulf. They also point to Texas, often the state Louisiana conservatives look to as a model. While it, too, is an oil and gas state, Texas has stepped up its renewable output in recent years. As of October, Texas provided 15% of America’s renewable capacity, while accounting for 13% of the nation’s CO2 emissions. Louisiana, by comparison, accounts for just 0.2% of the nation’s renewable energy, while producing 4% of America’s carbon emissions.

We need the Governors plan. I just hop[e that it is not killed by short sided political reasons.