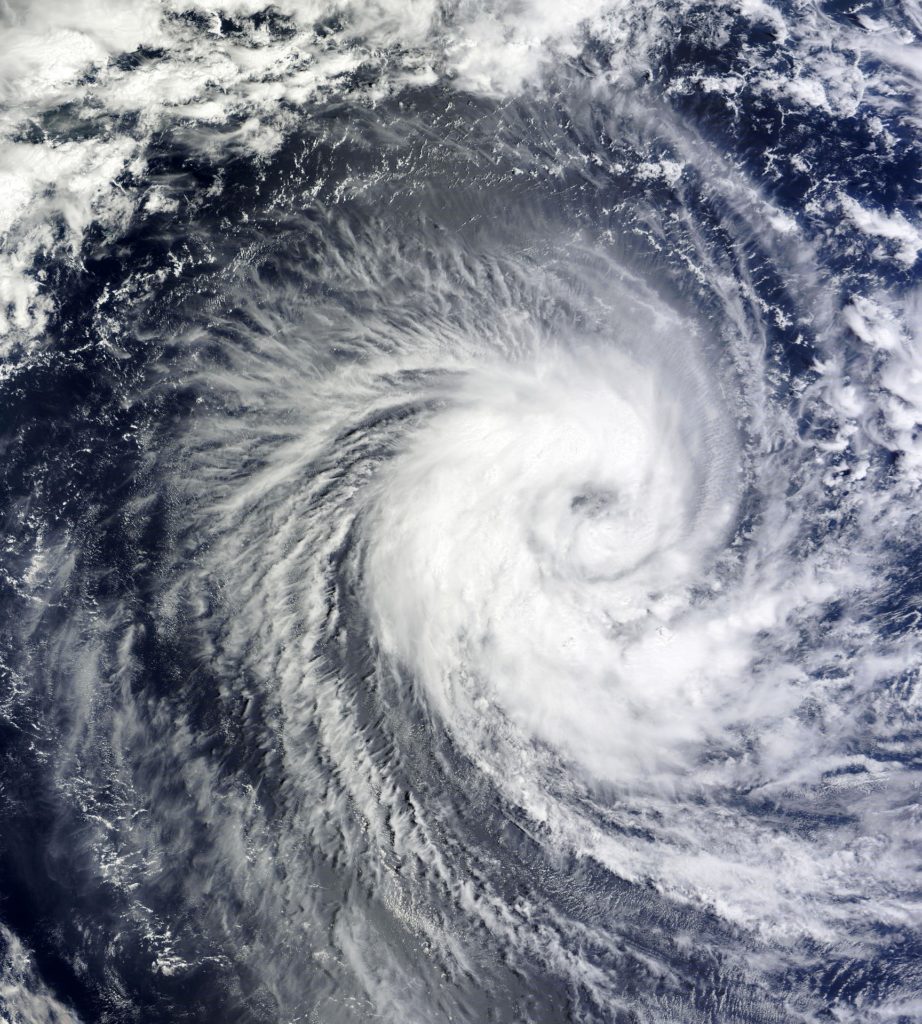

The hurricane path is uncertain, but sometimes had it varied a bit either east or west some would be saved and others lost. In this case a 15 mile difference made a difference.

If Hurricane Ida had made landfall just 15 miles east of Port Fourchon last August, its storm surge might have overtopped some locations along the West Bank hurricane levee system, National Hurricane Center officials said Tuesday. That eastern path also would have caused overtopping at some locations along the hurricane levee on the west bank of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish, and the Larose to Golden Meadow hurricane levee in Lafourche Parish, according to the center’s post-season report on Ida. The west bank levee and Lafourche levees, both refortified after Hurricane Katrina, are designed to withstand surges caused by storms with a 1% chance of occurring in any year, a so-called 100-year storm.

nola.com

The computer model showed that then the storm would have over-topped even the newer levees.

The report said the overtopping was predicted by the Sea, Lake and Overland Surges from Hurricanes (SLOSH) storm surge computer model, which is used by the center to develop surge warnings during the hurricane season. But the model can also point out the potential risk to the public of even small changes in a major storm’s track, said Jaime Rhome, the center’s deputy director. “You can’t look at the single black line of the forecast track because the hazards extend well beyond that,” Rhome said. “And while our forecasting has gotten really good, even small variations of 15 miles – very, very small – can mean a drastic difference in hazards to local communities.” Surge levels during Ida were 6 to 12 feet above ground along the coasts of Jefferson and Lafourche parishes and 6 to 9 feet at barrier islands on the west bank of Plaquemines. The model indicated that on the more easterly track, the heights of surge that moved farther inland would have been 5 to 7 feet higher than actually occurred, “and those higher water levels would have overtopped the levee” in some locations.

Over-topped, yes, but the model does not show how bad it might have been.

The report does not indicate how significant the overtopping might have been at any location, or whether it would have caused any damage. All three levee systems are built to new Corps standards that ensure they would still be in place if overtopped, which would limit the total amount of flooding. Rhome said a similar what-if exercise was conducted in writing the post-storm report on Hurricane Laura in 2020. In that case, the modeling showed that if Laura hadn’t wiggled just 20 miles east just before landfall, surge moving up the Calcasieu River would have reached elevations of as much as 20 feet above ground level. Rick Luettich, a researcher at the University of North Carolina who developed a different forecast model that is used by the Army Corps of Engineers to design area levees and by state levee systems to determine when to close surge gates, said a quick review of his model results during Ida on similar easterly track veers did not seem to show overtopping of the West Bank system’s levees. His model did agree that overtopping might have occurred in some locations along the Lafourche and Plaquemines levees, though. A spokesperson for the Army Corps of Engineers said the report shows that powerful hurricane surges can wash over even the best-built systems, and that the region’s system is designed to withstand such overtopping. “This report underscores that no matter how big the system is, there will always be the risk of a hurricane surge greater than the system’s elevations,” he said. “Residents should consider this residual risk when developing their hurricane season preparedness plans and be ready to evacuate if the order is issued.”

Some maintain that the levees would still have held and the flooding would have been contained.

Nick Cali, executive director of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-West, added he believes the west bank levees could have handled the surge, even on a path farther east. “During Hurricane Ida, the West Bank Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System protected approximately 210,000 residents and more than 8,300 non-residential structures on the west bank of Jefferson and Orleans Parishes, representing more than $1.3 billion in property values,” he said. “A post-storm assessment of the functions of levees, gates and the West Closure Complex, confirms that though Hurricane Ida was a major weather event that tested the system, it worked as it was designed without sustaining any damage due to the hurricane.” Windell Curole of the South Lafourche Levee District said the report jibes with what he communicated to the public in the days before Ida’s landfall, which was that “there was a real possibility” that people would see more than 7 feet of water in their homes. “With continued powerful storms, it is critical that we have to act like we are going to get hit hard,” he said.

Ida was a big one, remembered also for the black out, and it still is one of the worst to hit this area.

The report confirmed that Ida had top winds of 130 knots – about 150 mph – when it made landfall, equal to Hurricane Laura in August 2020 and the Last Island Hurricane of August 1856, the three strongest hurricanes to make landfall in Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. Category 5 Hurricane Camille was near its top winds of 173 mph when it crossed the mouth of the Mississippi River on its way to a Bay St. Louis, Miss., landfall on Aug. 18, 1969, making it the strongest storm to make a Louisiana landfall.

15 miles, not a great difference, but a distance that helped us.