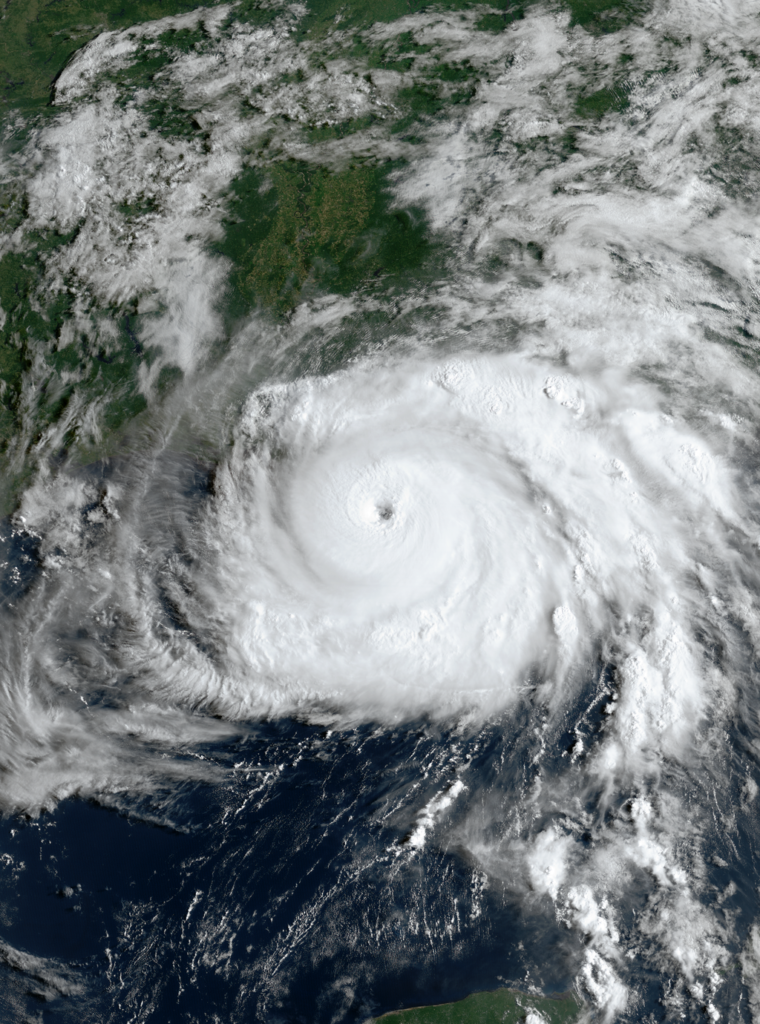

Hurricane Ida came through and immediately moved up the cost of damages scale. St John parish seems to be the worst hit and is still recovering. I still see blue roofs here so many are in this boat.

The fate of the old white house near the Mississippi River levee had been tested many times before, so when the path of Hurricane Ida shifted toward the Gulf Coast, Mercedes Bourgeois thought she’d remain in it. Far from the flood-prone subdivisions on the south side of LaPlace, the single-story house first built in the 1950s was no stranger to natural disaster. Hurricane Betsy (1965): “The worst one… We were without power for about a month.” Hurricane Ivan (2004), and then Katrina and Rita (2005). Hurricane Gustav (2008): “The first one I experienced without my husband,” the 84-year-old widow said. And who in St. John the Baptist Parish could forget about Hurricane Isaac (2012)? “This time, the storm was coming and I said: ‘I’m not going to leave my house,’ ” Bourgeois said. But each day before landfall the outlook got steadily worse as Ida slingshotted toward the Louisiana coast. Finally, her children intervened. “They grabbed me up and I just left,” she said. “The next day when I came (back) here, it was just horrible.” Parts of the roof were destroyed. One of the front doors was blown off the hinges. A tangle of woody debris was everywhere.

nola.com

Recovery can be slow especially if there is no home insurance to help pay for the damage.

Recovery may take Bourgeois longer than most, since she didn’t have homeowners insurance, a safety net that, on her fixed income, has long been too expensive for her to afford. She is but one of the thousands of St. John the Baptist Parish residents still wrestling with the aftereffects of last year’s storm. The parish saw an outsize share of its homes damaged by Ida’s winds and floodwaters, a Times-Picayune analysis of state insurance and census data shows. More than three out of every four — exactly 82% — of the homes occupied in the parish filed an insurance claim for wind damage, the analysis shows. That was more than any other parish in the state closely affected by Ida. And it’s likely an undercount, because of the many people like Bourgeois who did not have the extra financial protection. The analysis makes clear the disproportionate effect the storm, which tracked just west of New Orleans, had on a number of smaller parishes. More than half of the occupied housing units in St. Charles, St. James, Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes were damaged. Other parishes in the region, namely Jefferson, Orleans and St. Tammany produced tens of thousands more insurance claims after Ida. However, the claims filed accounted for a much smaller share of the housing stock.

St John has other distinctions making her in worse shape.

St. John is unique for another reason. More than half, or 58%, of the 7,000 households with policies in the National Flood Insurance Program have also filed an insurance claim, a separate analysis of flood claims data found. Most of those claims were concentrated in LaPlace, where close to three-fourths of the residents live and flood risk is the highest. The floodwaters came from the surge Ida pushed into the subdivisions near Interstate 10, which saw similar flooding in 2012’s Isaac. No other parish experienced flood damage on the same scale, the data suggests. The next closest, by comparison, is Tangipahoa Parish, where 10% of the 10,000 flood policyholders have filed claims, the data shows. A FEMA official said the data could change as more people file claims, though it’s now been more than seven months since Ida passed. The numbers give the clearest view yet of the damage done and what it might take to recover. “Our biggest concern for a homeowner is flooding again,” said St. John Parish President Jaclyn Hotard, noting that the federal government has finally allocated the $1.3 billion for the West Shore Lake Pontchartrain Hurricane Levee project, which aims to protect LaPlace’s rear flank. “Of course, it can’t come soon enough, because until it’s built we don’t have that flood protection,” Hotard said. “We know this levee is coming. However, between now and 2024, when it’s expected to be complete, could this happen again?”

There is hurricane relief money coming but how much will help cases like this?

The $1.7 billion in hurricane relief money set aside by the federal government for the state thus far will go a long way in getting communities back to normal. State officials say they expect the funds to begin flowing to residents close to a year after the storm. That’s a lot sooner than the lengthy wait victims of Hurricanes Laura and Delta faced after those storms crippled the Lake Charles area in the fall of 2020. State officials expect to launch long term housing programs for those storms this spring. “It’s already moved a lot faster for Ida because the appropriation came months instead of a year after the disaster,” said Pat Forbes, executive director for the state’s office of community planning. “While the Laura folks are going to be pushing up close to two years since their storm before the federal process lets the money get out the door. For Ida, that’s going to be closer to a year.”

There has been federal assistance but not all qualified.

FEMA has been offering relief aid for housing assistance, while the federal Small Business Administration has provided low-interest disaster loans. But the new funding announced on March 22 would flow from the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department to the state. Forbes said the main priority for the money is to fill unmet needs, particularly those of renters and homeowners. He said the state’s action plan for Ida will resemble those created for previous storms, allowing officials to swiftly make the money available to those who need it. “We know it’s critical that we get the money out quickly,” Forbes said. “We’ll do everything that we can to make that happen.”

The private sector, notably churches and other helping agencies, has stepped in to help.

Meanwhile, churches and other nonprofits have stepped in to fill the void in St. John. More than 1,000 volunteers funneled into hurricane-damaged communities this week to repair houses for people in need. The Tupelo, Mississippi-based group named Eight Days of Hope has organized the effort once or twice a year since Hurricane Katrina. Stephen Tybor III, the group’s CEO and executive director, said some 28 families will get a new roof and another 30 families will have their entire house repaired over eight days. “They have a need that can’t be met by FEMA or insurance companies because of either the lack of or not having the right insurance,” Tybor said. The group will be based out of New Wine Christian Fellowship, a church in LaPlace that has been organizing smaller groups of volunteers since immediately after the storm. “This is kind of like a steroid shot,” Tybor said.

One of the student groups came down from Maine.

One Friday in March, Mercedes Bourgeois turned to New Wine to help do what an insurance company might’ve done. She isn’t a member, but the pastor is an old family friend, she said. Through the church, about a half-dozen college students from Farmington, Maine were helping to repair some of the damage to her home. But because it’s all volunteers, she said finishing could take months. As the volunteers neared the end of their work day, Bourgeois was outside, studying the remains of a downed cedar tree that her father planted in 1974. There was only a short length of trunk left; the tree was snapped in half by Ida. The roots were still clinging to the ground, desperate for new life. A burly man who had been leading the students from Maine shook the uprooted stump, saying they should have had it dug up and hauled away.

The cycle is starting again with a hurricane season that is projected to have a number of big storms coming up.

Hurricane season starts in about two months, and some forecasters have already predicted that there could be as many as 19 named storms and 9 hurricanes in 2022. In due time, Bourgeois figures she will be thrust back into a familiar cycle: Fleeing from danger. Surveying damage. Struggling to rebuild. Does it ever become too much to bear? “I’ve got to the point where I can’t worry about it anymore,” Bourgeois said. “There’s not a thing you can do about it.”

The perils of living here!