Fire is a bad thing in a factory and a refinery. Especially if caustic and dangerous chemicals and gasses are made or used there. That is that happened at the Dow facility in Plaquemine.

A compressor caught fire and leaked liquid chlorine, sparking a release of the combustible and caustic chemical Monday night inside the Dow Hydrocarbons complex in Plaquemine. Parish officials were forced to close roads and order residents to shelter in their homes for several hours until the fire and leak could be brought under control, though it escaped Dow’s huge site along a bend in the Mississippi River at low concentrations, parish officials and state regulators said. The leaking chlorine, which remains in a liquid state only at extremely cold temperatures, pooled on the ground after the compressor failed but began quickly to turn into a gas, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality officials said Tuesday.

theadvocate.com

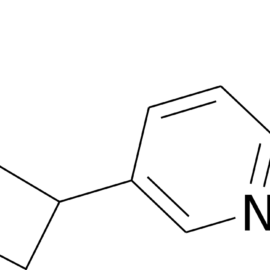

Chlorine is both made and used in this facility.

Produced by Olin Chemicals inside Dow’s complex and used to make other chemicals there, chlorine is dangerous as an escaping gas during a fire because chlorine can explode in contact with flames and, as a heavier-than-air gas, can also meander along the ground. Residents in the Plaquemine area were told shortly before 9 p.m. Monday to stay in their homes, turn off their air conditioners and close all doors and windows for about three hours after the leak and fire sent a huge plume of smoke into the air. Roads were also closed. Internal fire crews at Olin completely extinguished the fire in less than an hour and a half, by about 10 p.m., according to parish and state timelines. Clint Moore, Iberville Parish homeland security director and emergency operations chief, said crews also continued to put water on the leak, diluting the chlorine gas’s concentration, which helped send some of it skyward along with breezy weather that night. Had the chlorine gas been more concentrated and, thus, less buoyant in air, the gas could have more easily spread out across the ground and parish officials likely would have had to call for the evacuations of homes near Plaquemine, Moore added. “Because this was such a diluted cloud, the wind was able to carry it up and away, so to speak, from the houses,” Moore said.

A chlorine leak is one of the worst case scenarios in the petrochemical industry and so is treated seriously.

Chlorine gas leaks are among several worst-case risks surrounding Louisiana petrochemical industry, which relies on the element — sometimes made by breaking up the chemical components of brine extracted from the state’s salt domes — to help make plastics and variety of other chemicals necessary for modern conveniences. In 2020, Hurricane Laura triggered a fire and vast plume of greenish-grayish smoke at the BioLab Inc. complex, releasing an unknown amount of chlorine gas that blanketed Lake Charles. Most of the city’s residents had evacuated prior to the hurricane, and no serious injuries were reported. Moore said a variety of agencies and Olin were monitoring the air during the incident and detected low-level concentrations of chlorine escaping the 1,500-acre Dow property and heading south toward the community of Plaquemine. But concentrations were no more than 1 part per million, which is equivalent to about one cup of water in a swimming pool, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Short term exposure is not that serious and that was the case here.

In short-term exposures of a few minutes to a few hours, chlorine is far from lethal and hardly a significant health risk at 1 ppm or less. That takes concentrations that are tens of times higher, but even an exposure of four hours to 1 ppm of chlorine can induce an asthma-like attack in some people, a handful of studies have shown. According to an Environmental Protection Agency fact sheet, exposure to chlorine can irritate the eyes, upper respiratory tract and lungs. At higher levels, it can cause chest pains and vomiting. It is extremely irritating to the skin and can cause severe burns with high enough exposure. A greenish-yellow gas, chlorine is significantly heavier than air, so it tends to collect in low-lying areas, according to the World Health Organization.

The plant straddles the Mississippi in the Baton Rouge area.

The Dow site straddles Iberville and West Baton Rouge parishes. Located along bend in the Mississippi River, Dow is one of Louisiana’s largest petrochemical facilities, with more than 3,000 Dow and contract employees and 12 production units, the company has told regulators. Olin took over Dow’s chlorine, caustic and ethylene dichloride units in 2015. In an eight-month period in late 2016 and later in 2017, Olin’s operations inside Dow had three chlorine leaks that injured a contract worker and prompted worker evacuations and road closures. But emergency officials said at the time they never posed a risk to the public. One of the leaks, in December 2016, stemmed from a massive power outage that Entergy later said was triggered by the burning of sugar cane. The other leaks in September 2017 were caused after four electrical rectifiers tripped. Officials with Olin Chemical said the latest release caused no injuries inside the facility. “We will conduct a thorough analysis to identify the cause of the event. The safety of our employees, the community, and our environment is always our top priority,” Olin officials said in a statement.

The fire started Monday night.

Greg Langley, DEQ spokesman, said the fire and leak began at 8:38 p.m. Monday. Seven minutes later, Olin notified Louisiana State Police Hazardous Materials officers, who are the central point of contact and typically take control of sites during hazardous emergencies. Notifications to DEQ and other agencies followed from the State Police notification, prompting further agency responses. But parish officials said they first heard of the leak from a resident living near Dow’s complex, who reported a noise and the smell of a chemical odor at 8:40 p.m. After parish dispatchers verified with Dow’s control room that a fire was happening in Olin’s chlorine block, Moore said, notifications to the public through social media, telephones and television went out nine minutes later, about 8:50 p.m. By shortly after midnight Tuesday, authorities lifted the shelter-in-place order and soon afterward opened the closed La. 1 and Woodlawn Road once the risk of off-site exposure ended, company and parish officials said. Langley, the DEQ spokesman, said agency inspectors detected chlorine in the air on Olin’s site over night and were continuing to monitor the air Tuesday morning. He said residual releases were still occurring from liquid chlorine still pooled on the ground, leading to residual fence line detections of low concentrations of chlorine. “Community monitoring will continue for several more hours,” Langley said.

The public is not impacted but the public reported smells. DEQ has been on the site and say no public areas have been effected.

DEQ inspectors have been on the site since Monday night, and DEQ responders haven’t detected chlorine in the community since 6:15 a.m. Tuesday. Moore said authorities lifted the road closures and shelter-in-place orders because the amount of chlorine left on the ground won’t emit enough gas to escape the Dow/Olin site. Olin took control of some of Dow’s operations in Plaquemine after a $5 billion deal announced in the spring of 2015. That deal included Dow breaking off its Gulf Coast chlor-alkali and downstream derivatives businesses and merging them with Olin. Dow was under shareholder pressure at the time to split up parts of the company.

A case like this with these actors makes me look at my self. A large part of the problem today is that no one trust anyone. Yet do I trust the DEQ with all the times they have sided with industry? Do I trust an industry that has contributed to Cancer Alley? I then realize I am part of the problem this country is going through.