Before the Corps of Engineers started to try to control the Mississippi River, the river made new channels at will. Well, the river just opened up a new one proving that like Mother Nature, the river wins.

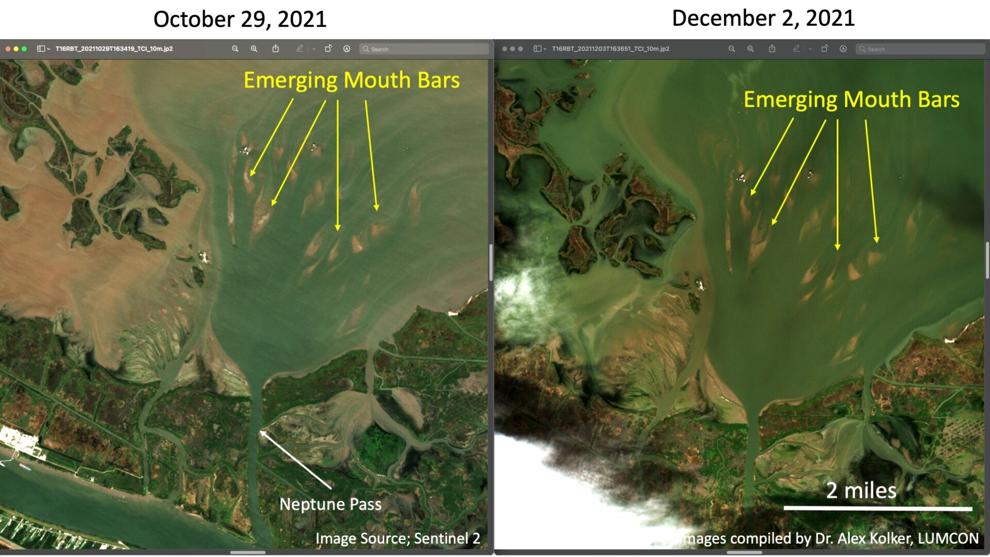

A gap in the Mississippi River’s banks in the waterway’s far southern reaches has widened into a full-blown channel, funneling huge amounts of water through it and prompting the Army Corps of Engineers to move to close it. But state officials wonder if it could also be a blessing from nature. The Corps has decided to close the entrance to the newly formed “Neptune Pass” with rock on the east bank of the Mississippi River, across from Buras. Its slowing of the water flow downstream is causing navigation issues in the river’s main shipping channel, a Corps spokesman confirmed Thursday. At the same time, the state is asking if allowing the pass to continue to funnel water into Breton Sound could help rebuild lost wetlands there. Sediment carried by the channel is already forming new land lumps in Quarantine Bay, part of the Breton Sound, and quickly filling in the landlocked Bay Denasse, according to Alex Kolker, a coastal research scientist with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium. In a research survey of the new 850-foot-wide waterway last week, Kolker and Dallon Weathers, a surveyor with Delta Geo-Marine, found that as much as 118,000 cubic feet per second of water and sediment was flowing through the channel, which had deepened to 100 feet near its juncture with the river.

nola.com

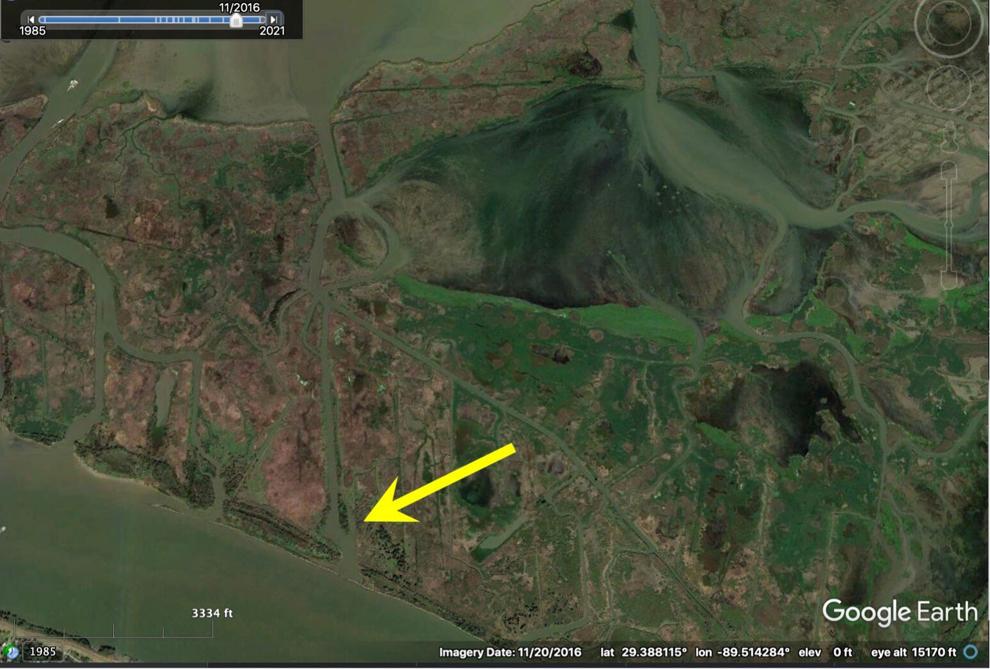

Initially contained, high water and hurricanes have widened the channel and finally broke through the restraining barriers.

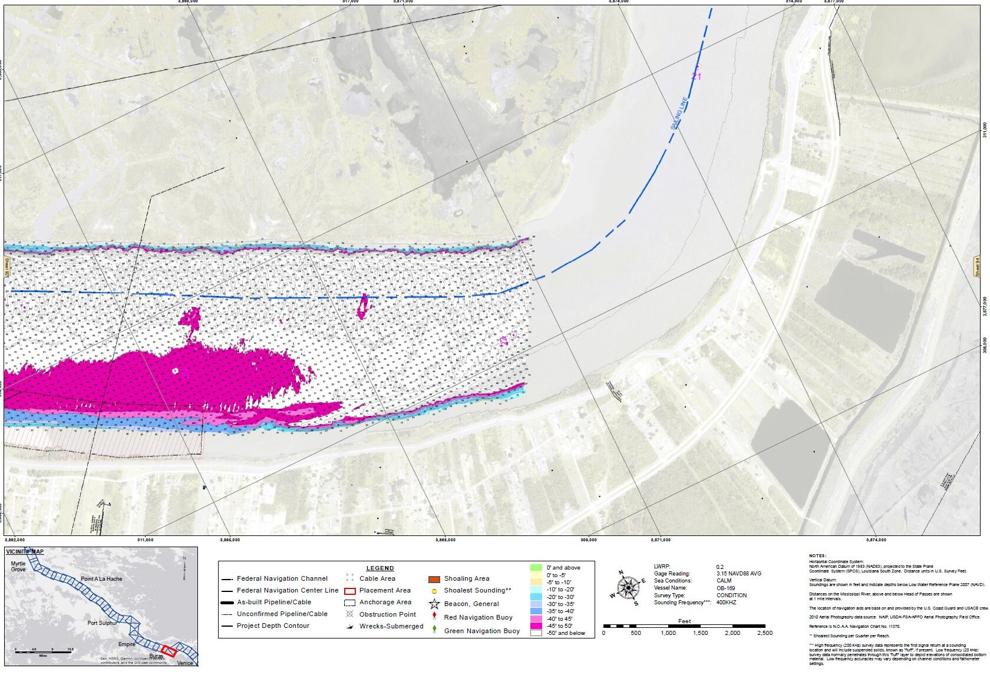

The crevasse connecting the river to Quarantine Bay is one of several small distribution channels that have formed along the lower river’s east bank in Plaquemines Parish, breaking through low levees and rock put in place to keep most of the river’s water flowing south through Southwest and South passes into the Gulf. In 2016, the channel was only 150 feet wide, but it has widened significantly since, possibly the result of repeated years of high river flows and several hurricanes. The diversion of part of the river’s flow east through the widened channel has slowed the flow of water in the river’s main channel, which is causing sediment to drop out, posing a threat to oceangoing vessels moving north toward New Orleans, said Corps spokesman Ricky Boyett. “As of May 25, we measured a little more than 16% of the Mississippi River flow being diverted at this location,” Boyett said. “Recently, we identified shoaling just south of the location in an area that we have never had shoaling previously.” The Corps had to have a dredge remove the shoaling from a 7/10th of a mile stretch along the western side of the main navigation channel in mid-May, he said. “This shoaling means that we are starting to see impacts to the deep draft navigation channel and will need to close the crevasse,” Boyett said.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

A rock blanket will be installed to try to block the new channel.

Contractors will lay a rock blanket over the clay base at the river’s bankline at the channel mouth, to block further erosion, beginning in July. Then a rock closure will be built in the pass to the east of the riverbank line. “While the primary purpose of this structure will be to address impacts to the navigation channel, we are considering features that will allow some water, sediment and small vessels to continue to pass through the closure,” he said. The result could be that the closure will include a 10-foot-deep sill to allow some freshwater, sediment and small boats to continue to use the channel to enter the bay, said Bren Haase, executive director of the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. “We are encouraging the Corps to address this as an opportunity (for coastal restoration through the creation of new land with sediment flowing through the channel), and not just a potential problem for the navigation channel,” Haase said.

(Google Earth, Prof. Alex Kolker, LUMCON)

There are other potential channels that will be looked at to see if they can be blocked.

Part of that discussion should include a review of the numerous other channels that allow river water to flow east into Breton Sound, to see if some of them can be closed to increase water flow in the area where shoaling is occurring, which could allow more water and sediment to flow through the new Neptune Pass, he said. According to Kolker, the river’s flow at Belle Chasse has been measured at 776,000 cubic feet per second by the U.S. Geological Survey. Mardi Gras Pass, a crevasse that formed 10 years ago near the Bohemia Spillway, siphons off 25,000 cfs to the east. Ostrica Locks, just north of the new Neptune Pass, captures 13,400 cfs, while channels near Fort. St. Philip capture another 104,100 cfs. That means as much as 36% of the river’s flow below Belle Chasse never makes it south of the new pass, which has slowed the water flow and caused the shoaling. “This, again, highlights the need to move toward a more holistic management of the river, where we are considering maintaining the longevity and resiliency of the navigation channel, but also considering flow control as an ecosystem restoration tool,” Haase said, “an opportunity, and not necessarily a problem.”

The unexpected land growth might help in the coastal restoration plans.

Haase said that while the new channel poses an opportunity for unexpected land growth on the east side of the river, it’s too soon to determine if it will result in any changes in the state’s broad coastal restoration strategy. “It certainly is an interesting event, though, to be able to monitor and understand the power of the river,” he said. “There are some subaqueous bars forming out there that look very much like we’ve seen at Wax Lake (on the west side of the mouth of the Atchafalaya River’s main river mouth), and in other areas where rivers have created new connections to the coast.”

(Google Maps, from Prof. Alex Kolker, LUMCON)

This should be part of a study to look t all of the land masses in the area.

Kolker said it’s equally important to look at this crevasse event as part of a broader scientific review of the future of land masses along the river, especially the birdfoot delta at the river’s mouth. “The immediate event is that a structure along the bank failed and the river took advantage, the weak spot,” he said. “But was this because the structure wasn’t built or maintained correctly, or is this part of a greater delta backstepping? “Some people think the mouth of the river might be moving backwards as the birdfoot delta sinks, and this could be part of that bigger change occurring in the river’s delta,” he said.

As we lose land it only makes sense that the opening will be closer to New Orleans.