IMAGE COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Diversions build land. The ones we see today build more marsh land but earlier ones built New Orleans. A bit of history!

Mention river diversions in southeastern Louisiana, and you’ll likely get an earful. Proponents hold that controlled openings of the Mississippi levee can replicate natural processes, by releasing sediment-laden fresh water into basins where saltwater has been intruding and marsh soils eroding. Opponents counter that river diversions can upset salinity regimes to the detriment of marine life, namely valued shellfish and finfish as well as dolphins, while injecting an excess of pollutants and insufficient quantities of sediment. Likewise, Louisianians in centuries past had opposing reactions to diverting river water, just as they had different motivations for doing so. Among them were irrigation, crop management, hydropower, and resource extraction. The people creating these early diversions were not government officials enacting public policy, but usually plantation owners pursuing private monetary interests.

nola.com

The earliest ones were small efforts to drain water so crops could grow and then, using the same channels bring water in in droughts.

On nearly every plantation along the lower Mississippi, planters directed enslaved laborers to excavate a network of ditches to drain soil water to the optimal level for the intended crop. During times of drought, and if river stage were high enough, those same ditches could be connected to a sluice cut through the levee, through which river water could be redirected to moisten fields. Different crops had different needs, and therein lay the controversy. Rice planters liked to inundate their fields to kill off weeds, whereas those raising sugar cane feared excess water would cause root rot. Neighboring planters thus disputed just how much water ought to be diverted, while all their neighbors fretted whether proper attention went into monitoring the sluice. If the river got too high, if the sluice gate malfunctioned, or if erosive currents scoured underlying soils, a levee might cave in, which could lead to a crevasse—that is, total levee failure causing destructive flooding. Crevasse floods were the premier reason for historical deluges in our region, and while most of them were attributable to shoddy levee construction, the shoddiness could often be traced to an intentional diversion gone amok.

One such diversion which caused problems was done by John M. Bell.

One notorious example was the Bell Crevasse of 1858, which occurred on the West Bank plantation of John M. Bell, upriver from the Harvey Canal. In colonial times, this had been a rice plantation, where a sluice had been installed to divert river water onto the fields. After rice cultivation gave way to sugar cane, the old “sluice was removed (and( filled with earth,” reported the Daily Picayune. “But the earth does not appear to have been packed with sufficient solidity, and when the river rose(,) it found the weak spot.” River water widened the fissure, and on April 11, 1858, it ruptured into a crevasse. Bell’s plantation went under fast-moving water, and as the crevasse expanded to 300 feet in width and 22 feet in depth, so did neighbors’ lands to the east, west and south. By mid-June, floodwaters extended “sixty-five miles (south and) still spreading out further,” reported the Jefferson Journal, “until there is a strong probability that the Mississippi will soon be connected by an unbroken sea of water with the Gulf of Mexico.” Not until autumn did the river stage drop enough for workers to repair the capacious breach—all traceable to a tiny decades-old diversion.

Other diversions were to enable mills to find enough flow to turn the wheels or the machinery.

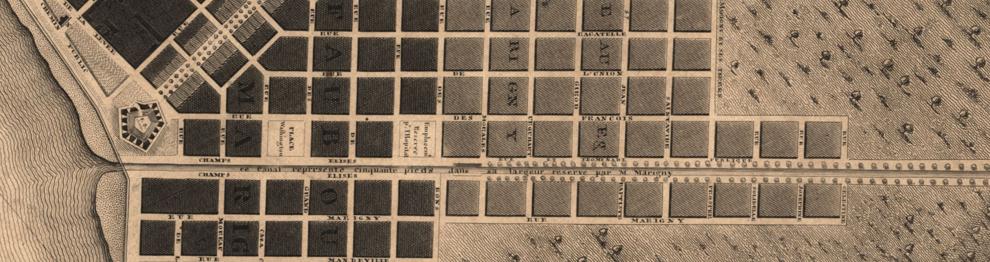

Another motivation for diverting the river was to harness energy. During high water, a well-positioned diversion could be made into a “mill race”—that is, a canal flowing with just enough hydraulic head to turn a water wheel to grind rice or saw wood. One early mill race was installed in the 1730s at present-day Algiers Point, when it was known as the Company Plantation, a colony-supporting operation of depots, facilities and fields of rice, tobacco and indigo. Rice being a critical food crop, engineers—probably Le Page du Pratz and Alexandre De Batz—had a sluice cut through the levee to steer river water down a race through a flume to a mill. The wheel astride the mill turned a stone to rub off the bran and leave behind the edible rice grains, which were then stored in an adjacent two-story warehouse. Another mill-race diversion operated across the river, in what would later become the Faubourg Marigny. There, around 1750, Claude Joseph Villars Dubreuil Sr. had his enslaved workers excavate a sluice through the levee at what is now the foot of Elysian Fields Avenue. About 200 feet inland, he built a moulin à planches (sawmill), where high river water would flow down the run and through the flume to power the saw. Dubreuil, being a big land owner as well as a shipbuilder and building contractor, benefitted in myriad ways from his sawmill. He harvested timber on his West Bank holdings and likely had the logs floated to his East Bank sawmill, whereupon he used the lumber for construction contracts. It’s possible that beams hewed at Dubreuil’s hydropower sawmill remain inside the Old Ursuline Convent, built by Dubreuil in 1752 and still standing at 1111 Chartres St. The sawmill lasted through the French and Spanish colonial eras, by which time the Marigny family owned the plantation, and the mill became known as the Canal del Molino de Don Pedro de Marigny. The sawmill appears prominently in a famous 1803 illustration titled “Under My Wings Every Thing Prospers,” made by J.L. Bouqueto de Woiseri to commemorate the Louisiana Purchase.

We are still impacted by these early efforts today.

The impact of Dubreuil’s diversion affects us to this day. Being perfectly straight, the mill race gave reason for engineer Nicholás de Finiels, hired by the Marigny family to subdivide their plantation in 1805, to lay out a wide avenue along the race’s trajectory. “The old sawmill canal determined the direction of the new streets,” wrote architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr., “the canal itself becoming the center of the principal street to which was given the name Champs Elisées.” Elysian Fields Avenue thus became the main axis of the Faubourg Marigny, and remains so today. According to historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Dubreuil owed much of his success to “African slaves’ technological knowledge—how to dam and control the waters of the rivers and bayous.” That know-how was by no means limited to Dubreuil’s plantation. “Many of the planters have saw mills,” wrote English Captain Philip Pittman in 1770. “(They) are worked by the waters of the Mississippi in the time of floods, and then they are kept going night and day till the waters fall.”

IMAGE COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The owners had other tricks up their sleeves to keep the mills working.

Even after river stage lowered, mills could be operated through some clever engineering. According to environmental historian Adam Mandelman, “some planters also built a series of check dams that could impound and store water in the backswamp, at their rear of their plantations. When the river subsided, this stored water would be released to power the mill in reverse.” River diversions could also be broadened into a canal wide enough to extract natural resources from the backswamp. Cypress logs, Spanish moss, clay, wild game, and other raw materials could be floated up to the front of the plantation, even as water flowing down the same canal could be used to irrigate, grind or saw. The era of private river diversions came to an end in the late 1800s as the federal government became increasingly involved in designing and financing the control of the Mississippi River. In the 1880s, government engineers adopted a policy of “levees only,” based on an understanding that strong, high levees would force the current to deepen its channel. All types of outlets, it followed, ought to be sealed off, be they natural distributaries or manmade diversions. Levees up and down the river were realigned, raised and strengthened, obliterating the old sluices, while revetments were laid to stabilize bankside soils.

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 changed the thoughts of those trying to moderate the river.

After the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927 overwhelmed the entire system and caused catastrophic flooding throughout the valley, engineers realized the folly of “levees only” and switched to an approach that also incorporated “safety valves,” such as the Bonnet Carre and Morganza spillways. By then, the era of sluices and mill runs had long since ended. But so too did the connection between the Mississippi River and its deltaic plain. Less and less fresh water made it out of the channel, and fewer sediment particles got deposited on adjacent swamps and marshes. All the while, ever more manmade canals were being excavated through coastal marshes, for navigation and petroleum extraction, each of which allowed saltwater to intrude and erode along lengthier shorelines. Along with other factors such as rising sea levels and natural subsidence, the digging of canals and the leveeing of the Mississippi has caused upwards of 2,000 square miles of coastal Louisiana to disappear since the 1930s. What to do? To many, including most coastal scientists, the answer is river diversions. But to others, including many coastal denizens, that answer is just as controversial as the river diversions of centuries ago.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of “The West Bank of Greater New Orleans,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” and “Bourbon Street: A History.” Campanella may be reached at http://richcampanella.com , rcampane@tulane.edu , or @nolacampanella on Twitter. As he says, diversions are not new and the controversy continues.