The Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet canal has been closed but has hurt the area with hurricanes.

The long-awaited repair of environmental damage to wetlands caused by the now-closed Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet shipping shortcut to downtown New Orleans has been given a significant boost with the U.S. Senate approval of legislation requiring the federal government to pay 90% of the costs. The language in the Senate version of the 2022 Water Resources Development Act, which it passed on Thursday, differs from that in the version approved by the House earlier this year. The House bill seeks to clarify that the federal government should pay for 100% of the restoration efforts related to the so-called MR-GO. The two versions will now go to a House-Senate conference committee to work out differences. “The measures we successfully worked to include in WRDA would help finish crucial projects in our state sooner and help restore important habitats in south Louisiana. I hope Congress sends this bill to the president’s desk soon so that the Corps can get to work on more key Louisiana projects,” said U.S. Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., in a news release announcing Senate passage of the bill.

nola.com

Army Corps of Engineers

The MAR-GO was built to aid shipping for vessels with a 36 foot draft but was made obsolete by bigger vessels with deeper drafts.

The MR-GO was built in the 1960s as a shortcut from the Gulf of Mexico to the Industrial Canal in New Orleans, cutting the time for ocean-going vessels with drafts of up to 36 feet to avoid the longer cruise up the Mississippi River, which also required use of the shallow lock from the river to the canal. But the channel quickly became obsolete, used by as little as one ship a day, as ocean-going vessels grew larger, with much deeper drafts. The canal also filled with sediment repeatedly because of hurricanes that required expensive dredging. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish officials along with environmentalists pointed to the canal as also acting as a shortcut for storm surge, labelling it a “hurricane highway.” Storm surge rose as it reached and overtopped hurricane levees at the intersection of the canal and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway at the northeastern corner of Lake Borgne, eroding away the levees and flooding Chalmette, New Orleans East and the Lower 9th Ward. In the aftermath of Katrina, Congress deauthorized the shipping channel and ordered construction of a dam just south of Bayou La Loutre to block saltwater from moving north. Construction of the Lake Borgne hurricane barrier as part of post-Katrina improvements to the levee system included gates that could block the flow of water from reaching the Industrial Canal.

Congress said the Corps of Engineers could develop a plan. They did only to have the project shelved with funding disputes.

Congress had also authorized the Corps to come up with a plan to restore the wetlands damaged by the canal’s operation, but state officials disagreed with the Corps’ decision in 2012 to require the state to pay 35% of what it estimated was a $3 billion restoration project. The plans included restoration along the canal, around Lake Borgne and in the Central Wetlands Unit that borders St. Bernard Parish and the Lower 9th Ward in New Orleans. Given the funding dispute, the Corps plan was shelved. In the years that followed, state officials and the Corps have moved forward on several proposals to restore wetlands along the canal’s path, using other funding sources, including money made available from legal settlements in the aftermath of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The reduction in the state’s funding requirements, however, would free up BP money for other coastal projects.

(Google Earth) Google Earth

The Water Resources Development Act was a catchall for Corps of Engineers projects.

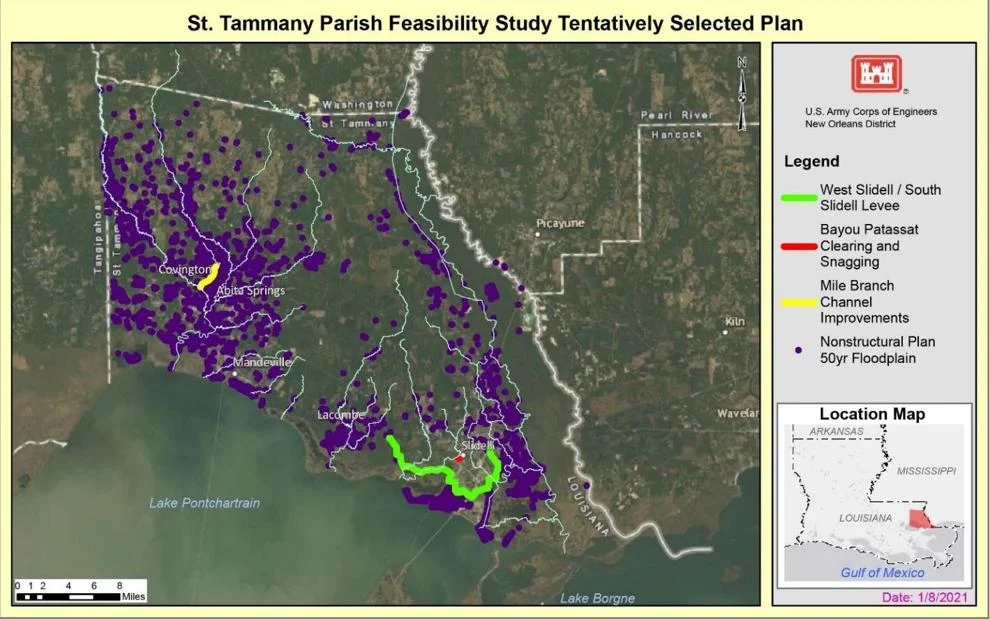

The MR-GO funding language was included in the Water Resources Development Act, a catch-all bill approved every two years that authorizes water and levee projects overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers. This year’s version also contained a number of other wins for Louisiana projects, including a go-ahead for the Corps to move directly into planning and design of the $4 billion collection of flood risk reduction projects proposed for St. Tammany Parish. Congress granted the Corps more time and money to complete a final version of its plan earlier this year. The draft plan calls for 14 miles of levees and two miles of floodwall in Slidell, clearing and snagging of Bayou Patassat, channel improvements in Mile Branch, and elevations and floodproofing for approximately 8,500 structures located in the 50-year flood plain. Congress must still appropriate money for construction costs for the different projects. The bill also requires the Corps to pay for the operation, repairs and other expenses of levees along the Algiers Canal on the west bank. The Corps notified state officials it would stop paying for the levees’ upkeep in 2009, and in 2019, the state filed suit against the agency, challenging the Corps’ interpretation of federal rules it cited in halting the work. The bill also requires the federal government to pay 90% of an ongoing Lower Mississippi River Comprehensive Management Study. State and Corps officials are using the study to determine how best to manage river water for use in sediment diversions like the proposed Mid-Barataria project aimed at rebuilding wetlands in Barataria Bay. It is also being used to look at how to better manage the use of the Bonnet Carre Spillway during high river years to reduce the effects of nutrient-rich river water on fisheries in Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi Sound.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

The bill still does more for Louisiana.

In addition, the bill authorizes a plan to use dredged material from deepening Belle Pass, which provides access to the offshore oil base Port Fourchon, to rebuild wetlands and Gulf beaches adjacent to the port. The Corps had originally questioned that plan as too costly under federal benefit-cost regulations because simply dumping the dredged sediment offshore would have cost less. Also included in the bill is language allowing the Corps to continue funding projects under the Louisiana Coastal Area program, which was authorized by Congress in 2007 to develop a variety of wetlands restoration projects in the state. Those projects include similar plans to use sediment dredged from ship channels along the coast for projects benefiting wetlands and coastal shorelines where the “beneficial use” costs are higher than other disposal methods. Congress would still have to appropriate money for the projects under the program. The bill also gave Congressional authorization to the 30.6-mile-long, $1.5 billion Upper Barataria hurricane levee system — designed as protection from storm surges for portions of seven parishes west of the existing West Bank and Vicinity levee system. The final design for the system was approved by the chief engineer of the Corps earlier this year. Construction can now begin as soon as Congress also appropriates construction money. Also receiving authorization is the $1.3 billion South Central Coastal Project, which will pay to elevate or floodproof 2,240 homes and businesses in Iberia, St. Martin and St. Mary parishes that are subject to storm surge flooding during tropical storms and hurricanes.

A lot of funding for projects that are needed. Not much fluff in these projects.