Parts of St Charles and St James Parishes flooded badly in Ida and over the next 4 years the Corps will strengthen their protection.

Areas of St. Charles and St. James parishes that have flooded badly during hurricanes will finally see their storm surge protection improved in stages over the next four years, an Army Corps of Engineers official says. East bank residents of the two parishes are benefitting from the long-delayed West Shore Lake Pontchartrain Hurricane Levee, the corps official told the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority board on Wednesday. The project has had to overcome years of funding shortages and court battles, and residents whose homes have been swamped by storm surge have paid the price in the meantime. By the end of 2026, the $1.2 billion levee system will be elevated to levels aimed at protecting Montz, LaPlace, Reserve and Garyville from hurricane storm surges that have a 1% chance of occurring in any year, a so-called 100-year storm.

nola.com

The hope is that this will stop the flooding. Ida was not the first time.

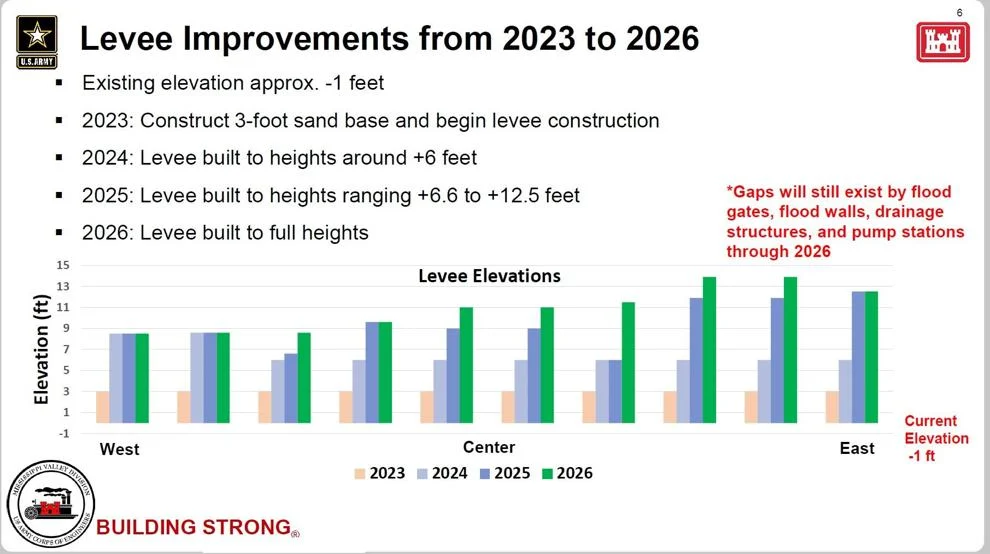

Federal and state officials hope the new levee will prevent a repeat of the devastating flooding of those communities by surge water moving west and south from Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain during Hurricane Isaac in 2012 and Hurricane Ida in 2021. By the end of 2023, workers will have installed a 3-foot sand base and will begin construction of earthen levees along the project’s 18-mile footprint, which borders Maurepas Swamp. Because the swampy area where the levee is being built is at about a negative 1-foot elevation, that will actually provide an initial 2-foot speed bump to protect against tidal flooding and small storms by the end of next year, said Mark Wingate, deputy district engineer for the Corps’ New Orleans District office. The sand and clay will be moved into place by dump trucks over nine access roads that are being built from populated areas along U.S. 61 into the swamp. The Corps is using sand and clay from a variety of sources, including material mined from the Bonnet Carre Spillway, and from privately owned borrow pits. By the end of 2024, the earthen levee part of the project will be elevated to 6 feet above sea level. By the end of 2025, the levee heights will range from 6.6 feet to 12.5 feet.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

This is called “staging” and it helps secure the base.

Wingate said the “staging” of levee lifts over several years allows the clay to compact, squeezing out water and air, and to also compact the soils beneath it, adding stability. By 2026, the earthen levee segments will be elevated to their authorized heights: 15 feet above sea level where the levee joins the spillway’s western guide levee, and dropping in height as it moves west, to about 8.5 feet where it joins the Mississippi River levee just west of Garyville. Concrete structures that are part of the levee system, including four floodgates, two drainage structures and four pump stations, will be built to heights of 19.5 feet above sea level near the spillway, and to 16 feet farther west. The higher structures are designed to match expected sea level rises caused by global warming through 2070. The earthen levees also are likely to be elevated several times between 2026 and 2070 to keep them at the proper heights to continue to provide the 1% surge protection. Wingate said the Corps is still working on designs for two smaller ring levees that will provide flood protection to portions of Grand Point and Gramercy in St. James Parish, while corps and local officials review how to deal with drainage in the area.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

They are considering the addition of natural hurricane suppression methods.

Senior Corps officials also must still make a decision on a proposal by the CPRA to use its proposed Maurepas Diversion project, which will channel water from the Mississippi River into Maurepas Swamp to help improve growth of cypress and tupelo trees, as part of the required mitigation for the environmental effects of the levee’s construction. If approved, the state would be able to avoid paying up to $120 million for other mitigation efforts. The New Orleans District office already has approved the plan, but senior officials must determine whether the state project meets federal rules that require mitigation, including whether the diversion must be completed before the levee project has ended. Wingate said Corps headquarters officials expect that decision to be announced in November, though local Corps and state officials have been lobbying to speed up the decision-making process.

Both the state and the Federal Corps are paying for this work.

Of the $1.2 billion total, the levee is being built for $760 million, with the state responsible for 35 percent of the construction, plus arranging ownership of the land. When complete, the levee will be operated by the Pontchartrain Levee District. The Corps also has received another $453 million in Hurricane Ida federal aid to apply lessons learned from that storm to upgrade the levee’s design. New Orleans officials are working on a $3 million reevaluation report focusing on adding resiliency to the new levee system, which would be paid for with that money, Wingate said. During Wednesday’s meeting, CPRA Executive Director Bren Haase also updated the board on on the status of a project improving a southern section of the Larose to Golden Meadow hurricane levee. While Hurricane Ida didn’t overtop that part of the system, a concrete T-wall 15 feet above sea level was replaced with an A-frame designed section of steel sheet piling that is 18-feet high.

The use of both natural and man-made preventive work seems to be the best option and not just because it saves money.