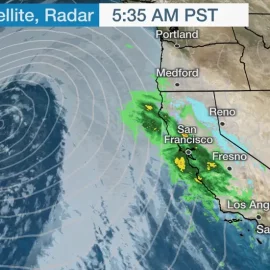

California, usually a leader for what will come, took the bull by the horns and bans non electric cars by 2035. Eugene Robinson comments and agrees.

From its pop culture to its politics, California has long been a bellwether of America’s future. The state’s bold new rule phasing out gasoline-powered, carbon-spewing cars and light trucks is a big leap toward ensuring that the whole planet has a future at all. The transition away from gas guzzlers that contribute to climate change is already underway. What California’s welcome rule accomplishes is an ambitious new timetable. The California Air Resources Board told automakers Thursday that the percentage of new zero-emissions vehicles they sell in the nation’s most populous state must begin climbing steadily in 2026 — and must reach 100 percent by 2035. No more than one-fifth of those new cars can be plug-in hybrids. The rest must be fully electric or run on some other zero-emissions technology. What makes this such a big deal — aside from the fact that if California were a country, it would be the 10th-largest automobile market in the world — is that 15 other states follow the zero-emissions standards set in Sacramento. If they sign on to this mandate, too, the rule would cover more than one-third of all new vehicles sold in the country, essentially giving California the power to set emissions policy for the whole nation.

Some object to this but many automakers agree.

Automakers such as Toyota, General Motors, Ford, Volkswagen, BMW, Honda and Volvo have in recent months affirmed their support of California’s right to set emissions rules. That might be because they’d like to be eligible to sell vehicles to the state government. And even before California announced its new rule, the industry was already racing to make the switch to zero-emissions vehicles because consumers are demanding them. Transportation accounts for roughly 40 percent of California’s greenhouse gas emissions. By 2040, the new policy is expected to reduce the carbon footprint of passenger vehicles in the state by more than half, even when taking into account the fossil fuels that might be burned to generate the electricity needed to power zero-emissions vehicles. The rule is “one of the most significant steps to the elimination of the tailpipe as we know it,” Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) told the New York Times. “Our kids are going to act like it’s a rotary phone.”

Now that this is set, there will be movement to enact this across the country.

Deadlines concentrate the mind. The next few years are going to require a lot of hard work and innovation — much of which is already taking place. As recently as 2018, 86 percent of batteries that powered electric vehicles required cobalt, a fairly rare metal. Experts predicted dire shortages that would limit industry capacity. But automakers — first in China, now in Europe and the United States as well — began using a different battery technology, and today only 60 percent of vehicle batteries require cobalt, according to Bloomberg News. That percentage is expected to continue to fall. What must continue to rise, however, is the range of electric vehicles and the availability of rapid-charging stations to power them. I drive an electric car that will go about 225 miles on a full charge — more than enough for everyday driving and weekend excursions. This summer, our neighbors drove their new Tesla to Texas and back, no problem. There are enough charging stations out there to make that sort of trip possible — but not enough to make drivers like me feel comfortable enough to go all-electric-all-the-time. We use a plug-in hybrid for long trips.

There will be charging stations set up and the infrastructure bill gives money for this.

Last year’s bipartisan infrastructure bill included $5 billion over five years to build a national network of charging stations. That will definitely help, but it’s just a start. Why not repurpose some of the nation’s 145,000 gas stations, whose business is bound to decline? Another speedbump on the road to our all-electric future is that batteries don’t like cold weather. My car’s range probably drops by 15 percent in the winter, though the Norwegian Automobile Federation —which ought to know — found that the decline can be more like 20 percent, and charging goes more slowly. If I lived in Maine or Minnesota, that would potentially be a problem. Overall, though, this should be a moment of considerable optimism. One reason is that electric cars are so much fun to drive, with acceleration that puts old gas-powered muscle cars to shame. Another is that there is hardly any maintenance to speak of — no oil changes, no spark plugs to replace, no radiator coolant to worry about. And Dodge, which just announced the demise of its iconic gasoline-powered Charger, has figured out a way to make its coming new all-electric Charger snarl and roar just like the old one — engineering virtue to sound deliciously like vice. California’s regulation affects new cars only, so used gasoline-powered cars will still be on the road in the state in 2035. Eventually, though, I hope they will become rare antiques. I look forward to the day when a whiff of exhaust evokes nostalgia rather than a sense of doom.

My son has a hybrid and an EV. My next car will be a hybrid and if we get another it will be an EV.