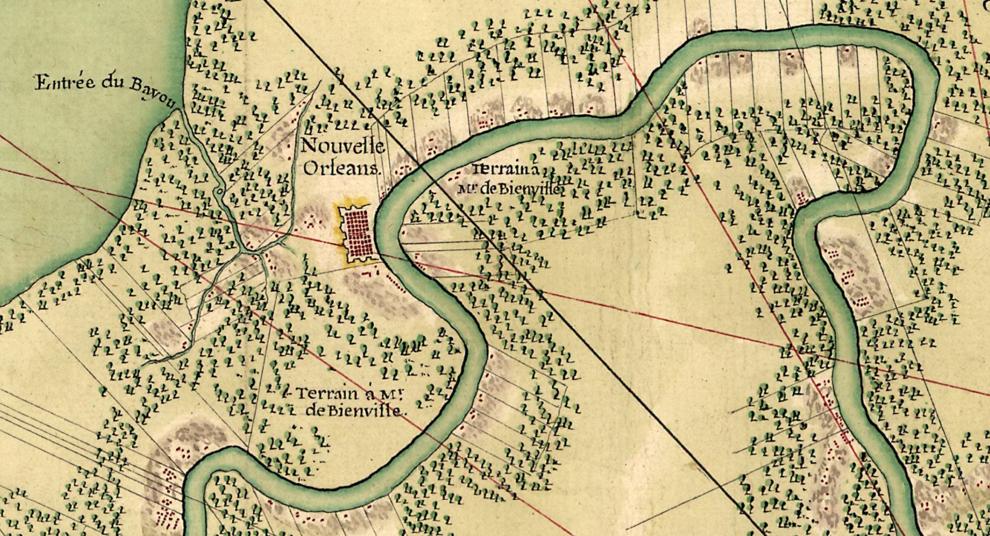

The first recorded hurricane her was a doozy. But thanks to it the city developed to what it is now.

The first gusts arrived on Sept. 10, 1722, jostling ships docked along the riverfront and growing steadier overnight. Around 9 a.m. next morning, “a great wind” came, wrote Adrien de Pauger, “followed an hour later by the most terrible tempest.” It was New Orleans’ first hurricane, 300 years ago this month, and while its track likely coursed eastward, close to Mobile, its size and intensity — at least a Category 3, by one modern estimate — affected the entire central Gulf Coast. The surge in the Gulf of Mexico reversed the flow of the Mississippi River, such that “the river rose more than six feet and the waves were so great that it is a miracle that (all the boats) were not dashed to pieces.” The winds, wrote Pauger, who served as the colony’s assistant engineer, “had overthrown at least two thirds of the houses (plus) the church, the presbytère, the hospital and a small barracks building…without being, thanks to the Lord, a single person killed.” “With this impetuous wind came such torrents of rain, that you could not step out a moment without risk of being drowned,” wrote a colonist named Dumont. “It rooted up the largest trees, and the birds, unable to keep up, fell in the streets. In one hour the wind had twice blown from every point of the compass.”

nola.com

The storm lasted a couple of days and did a lot of damage.

Not until 4 a.m. on Sept. 13 did the gusts finally abate, at which time New Orleanians “set to work to repair the damage done,” including the loss of 34 houses, five ships, various flatboats and pirogues, plus cargo and cannons. Nevertheless, the hurricane of 1722 created an occasion for what disaster experts today might call “adaptive resilience” — that is, a chance to modify designs to make the next disaster less traumatic. To understand how the city responded, we have to go back a few years, to the earliest conception of New Orleans. In the summer of 1717, officials in Paris conceived of a headquarters for a highly speculative company promising to transform Louisiana into a mercantilist colony supplying France with riches. Officials resolved to establish a city to be named “New Orleans” — the name flattering Philippe, the Duke of Orleans — where, according to the company’s ledger, “landing would be possible from either the river or Lake Pontchartrain.” The charge would become the responsibility of Louisiana Gov. Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, who knew all too well the paucity of viable sites for a city in this flood-prone delta.

PHOTO PROVIDED BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Bienville selected what is now the French Quarter which upset the other Gulf cities who did not want more competition.

The site that Bienville eventually selected — today’s French Quarter, accessible to the lake via Bayou Road and Bayou St. John — had detractors in the other French outposts of Mobile, Biloxi, Natchez and Natchitoches, none of which wanted to see the rise of a rival. Company officials in Paris were skeptical as well, and after perusing in Paris, they recommended relocating the project to the headwaters of Bayou Manchac just south of today’s Baton Rouge. But the message never made it to the colony, and in the spring of 1718 Bienville’s men proceeded to clear vegetation at his favored site, by today’s upper Decatur Street.

As they developed the city they had trouble with – water.

One grueling year into the project, the river overflowed upon the primitive outpost, and even Bienville came away dispirited. “The site is drowned under half a foot of water,” he wrote; “it may be difficult to maintain a town (here).” Company officials heeded the cue and in January 1720 designated Biloxi as the new capital, a decision also justified by concerns that ships could not negotiate the Mississippi’s strong currents and shoals, and should therefore transship to smaller vessels at a coastal location. Even bigger problems loomed in Paris, as rumors spread that the struggling Louisiana colony was not yielding the company’s promised riches, and that the men behind the scheme had effectively scammed investors. Stock values plunged; riots broke out; company officials scrambled to control the damage; and New Orleans dropped even lower in priorities. As for the city itself, one observer described “New Orleans, in 1720, [as] a very contemptible figure[,] about a hundred forty barracks, disposed with no great regularity, [with] a few inconsiderable houses, scattered up and down, without any order.” Disorderly, flood-prone, demoted, nearly bankrupt: New Orleans verged on utter failure.

Engineers to the rescue.

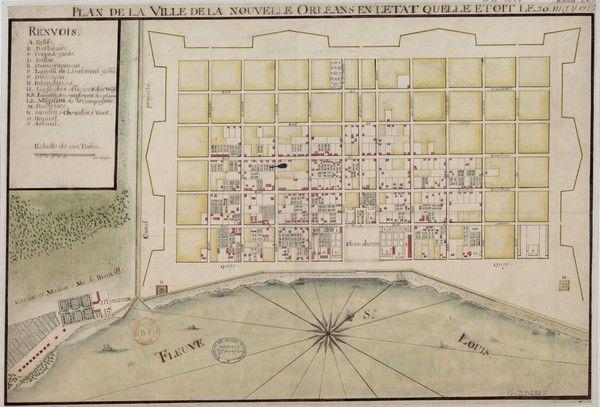

What helped turned the tide was the March 1721 arrival of Adrien de Pauger, assistant to chief engineer Le Blond de La tour, who went off to the more important job of designing the new capital at Biloxi. The diligent Pauger surveyed the terrain, studied the river’s hydrology, and got to work. From April through August, he sketched a series of plans for an orderly, fortified city — today’s French Quarter — and emblazoned them with the words La Nouvelle Orleans, along with street names honoring French royalty. Either Pauger or Bienville, New Orleans’ two biggest advocates, had the maps shipped back to Paris, presumably to show their progress and indulge their superiors with the honorific nomenclature. To officials mired in the tense financial restructuring of the company, the impressive maps were just about the only good news coming out of Louisiana. Along with other factors, the maps seemed to have played a key role in changing the perception of New Orleans in both company and government circles. On Dec. 23, 1721, officials in Paris decided to make New Orleans and not Biloxi the new capital of Louisiana, and New Orleans got a new lease on life.

map_courtesy of Library of Congress

The plan was good but the actual work on the ground paid little or no attention to the plan.

As the news made its way across the ocean, Pauger found himself vexed by the disparity between his orderly vision for New Orleans and the reality on the ground, where crooked houses blocked his planned streets, and insolent villagers rebuked his reprimands. How to clear all this mess and start afresh, creating a city worthy of the designation of colonial capital? Nature did exactly that, in the form of the Sept. 11, 1722 hurricane, and the destruction it caused was disastrous by any standards. But what it also did, figuratively speaking, was “wipe the slate clean.” That expression is used all too often in the wake of modern disasters, and it is usually misleading. Most communities, particularly venerable cities, represent such enormous amounts of prior investment — creating such deep repositories of economic, social, and cultural value — that even major catastrophes fall far short of “wiping the slate clean” — that is, completely detaching people from their place. But in 1722, New Orleans was simply too incipient and improvisational to have engendered any place-based value, and no colonist longed for a return to the prior mess. Even if they did, it’s worth noting that this was no democracy; it was a colony of an absolutist monarchy. Leaders, not the people, had the last word, and enslaved residents (around 37% of the city population at the time) had no word at all. Pauger could now proceed unimpeded in laying out his meticulous city plan. “All these buildings were temporary and old,” wrote his boss and collaborator Le Blond de La Tour of the destroyed houses, “not a single one was in the alignment of the new town, and they were to have been pulled down. Little harm would have been done, if only we had had shelters for everybody.”

(National Library of France)

The hurricane came and the work began.

Dumont described what happened subsequently. Workers “cleared a pretty long and wide strip (now Decatur Street) along the river, to put in execution the plan (Pauger and De La Tour) had projected. (They) traced on the ground the streets and quarters which were to form the new town, and…to each settler…gave a plot.” Settlers had to fence their parcels and “leave all around a strip at least three feet wide, at the foot of which a ditch was to be dug, to serve as a drain for the river water in time of inundation.” New and better houses were built by the score, this time raised above the grade and in alignment with the streets. Levees were strengthened, drainage gutters were installed, and designs were made for a slipway to protect vessels from future storms. Enslaved workers did much of the labor in the dramatic transformation. Within two months, wrote historian Heloise H. Cruzat, “the streets of the old quarter had received the names they still bear.” Wrote Dumont, “New Orleans began to assume the appearance of a city.” It took five solid years to launch New Orleans, starting with the 1717 resolution, a tenuous foundation in 1718, and three years of strife. But with the help of visionary engineers, good urban planning and a paradoxically helpful hurricane, New Orleanians were able to adapt, improve, and will themselves a future.

Today we worry about subsidence and rising waters. Thanks to the first hurricane for making the city what is is.