The Devils Swamp Superfund site is still polluted and when will it be cleaned up?

As far back as the 1960s, concerns were being raised over pollution at Devil’s Swamp, where families once crawfished and hunted north of Baton Rouge. “When will we ever be able to lift the advisory against eating fish and other critters out of the swamp?” said Jerry Speirs, a New Orleans attorney whose family owned farmland adjacent to the swamp when the contamination was first reported. His late father-in-law, Dave Ewell, sought to draw attention to the issue in 1969. But more than a half-century later, the area that is now a Superfund site has still not been cleaned up. New plans running on two separate tracks promise a 30-year cleanup, accompanied by possible projects to improve natural resources and provide infrastructure for future fishers and hunters. But none of the plans call for compensating affected families in a nearby majority-Black community. Federal and state officials have begun a new review of the effects of toxic hazardous wastes that have contaminated Devil’s Swamp to determine whether additional steps are required to mitigate damage to natural resources, including several threatened and endangered species, or to compensate the public for their loss.

Mark Schleifstein for nola.com

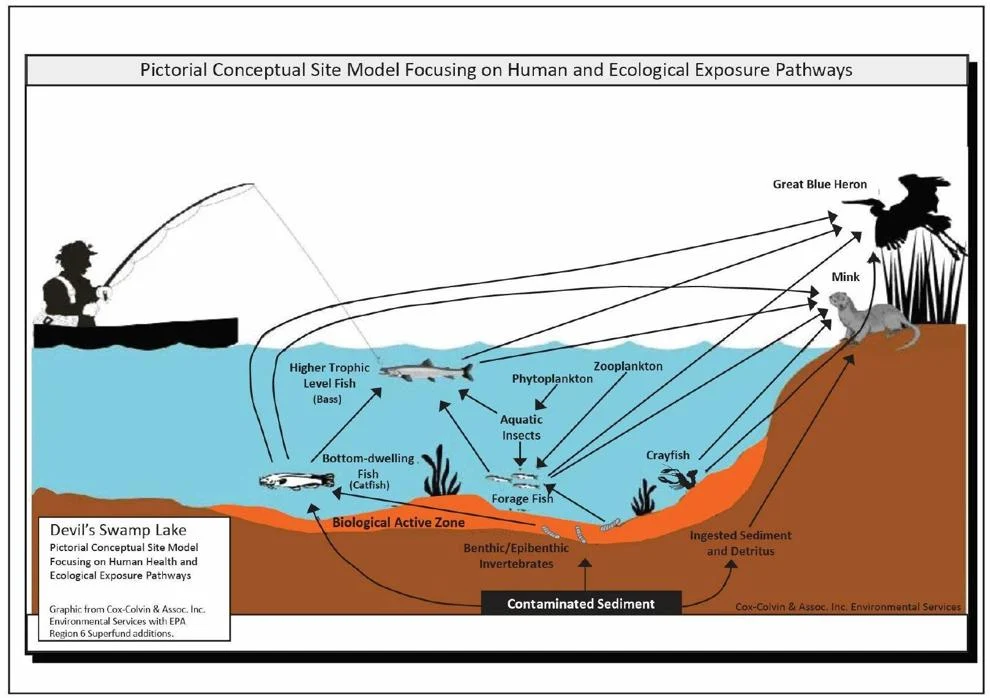

Pollutants, including PCB’s, have been reported and have made the swamp un-fishable.

(Google Earth)

Some of those near the water want the state to buy out their homes.

(Photo by Keith Horn, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality)

The damage has spread to other water bodies.

(Environmental Protection Agency)

The sites history and ownership are murky, like the water.

(EPA)

PCB’s were a common chemical that was banned in 1979 after studies showing it caused damage to nature.

The cleanup will be a two year process followed by a 30 year monitoring plan.

A damaged levee has been deemed responsible for letting the polluted water seep into other waterways.

Clean Harbors Environmental company is already working in the area.

These Superfund sites and the lack of funding to clean them up has been a constant problem especially when we keep finding them.