The infrastructure bill was a start but the electric companies want more.

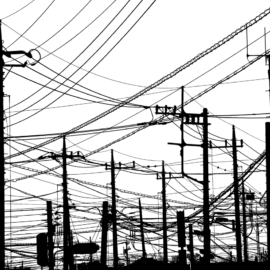

The $1 trillion infrastructure bill passed by Congress last month contains significant investments in Louisiana’s electrical grid, which was exposed as frail and outdated by a series of hurricanes over the past year. The state is in a position to get a sizable chunk of the $27 billion earmarked for items like new transmission structures, “smart grid” technology and storm hardening. That’s because the bill, championed by U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy, favors states struggling to recover from disasters. But the money — Louisiana will only get a fraction of the total — is nowhere near enough to build the type of grid that a growing number of regulators, consumer advocates and policy makers say is needed along the Gulf Coast, where hurricanes are becoming more powerful and frequent because of climate change.

nola.com

The Public Service Commission and the City Council are looking into what is needed.

The Public Service Commission and the New Orleans City Council, Louisiana’s two primary utility regulators, are embarking on probes into the weak spots exposed by Hurricane Ida and other storms that hit south Louisiana in 2020 and 2021. And they face a harsh reality: strengthening Louisiana’s grid will mostly depend on how much more customers can afford to pay on top of what they are already paying simply to repair damage. That is, unless the state can find another way to cover the costs. Craig Greene, chairman of the PSC, said there will soon be three different probes exploring the issue. The first, opened in 2019, will create new rules for what the poles used by power companies are made from and how often they are inspected, among other things. Greene opened two more dockets last month. The PSC will hire engineers to investigate the present state of the grid and what needs to be done to harden it. It will also explore things like microgrids and distributed generation, in which the generation of power is widely dispersed, instead of emanating from a single source. Greene said he wants to start with what Louisiana would do under a “Santa Claus” scenario, where money is no issue. The idea is to work backward from there.

Doing nothing is the wrong way to go.

There is a growing consensus in Louisiana that doing nothing is untenable. Storms are expected to wreak increasing havoc on the grid in the coming years, leaving ratepayers to pay for restoration, not to mention the costs of extended power outages: hotel stays, spoiled food and gas-powered generators, to name a few. In 2019 and 2020, Louisiana had one of the least reliable distribution grids in the nation, according to data published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In 2020, the year storms wreaked havoc on southwest Louisiana, the state ranked No. 1 in the country for the number of minutes power was out for each customer on average. Even excluding “major events” like hurricanes, only four other states had more minutes of outages than Louisiana. When comparing states based on the number of outages, Louisiana was second in the nation. It was ranked sixth and third for those respective metrics in 2019, a year when only Category 1 Hurricane Barry hit Louisiana. Those grim truths have prompted a wide range of experts to call for federal aid. “We really need help from the federal government,” said Greene, who wrote a letter to President Joe Biden after Ida. “I’ve got people that reach out to me every day that are on fixed income and their electricity bills are higher.”

Entergy is in a hole but I wonder how much they gave back to investors rather than spending the money on hardening the system.

Entergy faces $4.1 billion in estimated restoration costs for Ida and the 2020 hurricanes. That has forced the utility to take the unusual step of asking the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for permission to borrow billions of dollars ahead of schedule. Entergy Louisiana could eventually charge customers $15 a month for 15 years to cover that bill, it told the PSC recently. In response, FERC Chairman Richard Glick and Commissioner Allison Clements said the request underscores the “deep costs of climate change and extreme weather, which will ultimately be borne by customers.”

Different risks require different grids.

Utility experts say Louisiana needs to invest in several different types of grid hardening to account for the risks presented by hurricanes in different parts of the state. For instance, burying power lines, while expensive, can save money in the long term in places where wind is the major risk, and not flooding or storm surge. New Orleans already has some underground lines in the Central Business District and other areas on relatively high ground. In the mid-2000s, Entergy spent $15 million burying power lines that cross the Mississippi River to settle a long-running dispute with Carnival, whose cruise ships couldn’t sail under the utility’s overhead lines. Experts say power companies should also replace aging poles that were not built to withstand high winds, elevate substations so they don’t flood and invest in technology that makes it easier to remotely operate electric infrastructure. Ted Kury, who heads a utility research lab at the University of Florida, said there’s no single strategy to protect against hurricanes. Investments need to include a combination of all the above. Entergy has acknowledged climate change puts the grid at risk, and has agreed that more storm-hardening is needed. But not everyone is in agreement on how fast that work should be done, and where the money should come from.

Should the government pay? Or the company? Or the consumer?

The New Orleans City Council has exchanged barbs with Entergy New Orleans, which it regulates, over whether the company has made a sufficient effort to harden the grid. The council urged FERC to break the cycle of “patchwork system fixes” by looking for alternative models for paying for storm costs and upgrades. After Ida, council members wondered aloud whether they could make Entergy pay for storm restoration costs, instead of residents — a tricky proposition. Entergy New Orleans’ parent company has said its transmission system “proved to be resilient,” and highlighted the strength of Ida’s winds, some of the most severe to hit the state. In federal regulatory filings, it called the damage to seven of the eight transmission lines powering the city “minor.” And it boasted of the $2.5 billion Entergy New Orleans and Entergy Louisiana spent on transmission from 2016 to 2020. “Hurricane Ida demonstrates the resiliency benefits of these investments,” Entergy New Orleans wrote, adding it was the distribution system — the neighborhood-level network of poles and wires — that was “devastated” and slowed the return of service.

Were thing that rosy or are the problems we need to fix.

Some observers and customers took a less sunny view of the disaster; a class action suit filed against the company cited “shotty maintenance” for the outages. Ida knocked out all eight sources of transmission into New Orleans, including toppling a tower in Avondale. Ben Schott, head of the National Weather Service in New Orleans, said the highest wind speed recorded in the area, a gust of 113 mph, happened on the city’s western flank, where that structure is located. A similar debate about how much damage should be expected from a hurricane has gone on for years. Hurricane Gustav in 2008 left only one of 14 transmission lines connecting the city to the state’s grid intact. (Those 14 transmission lines covered a different area, from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, than the eight transmission lines that went down during Ida, knocking out power to all of New Orleans, an Entergy spokesperson said.) Regulators said then that Entergy needed to invest. Entergy responded that its grid was solid, and pointed to the fact that the transmission tower failures represented less than 1% of all towers, according to a Times-Picayune article at the time. That’s similar to a refrain from Entergy after Ida, which knocked down about 3% of the poles in Louisiana, according to utility officials. “I think people need to understand this is a long-term plan,” Phillip May, president and CEO of Entergy Louisiana said in an interview last month. “Louisiana has 1 million poles. We lost 30,000 poles as a result of Hurricane Ida. That’s a huge number but it’s a small percentage of our whole system.”

Entergy is using better towers but the problem is often the poles on every street.

Since 2014, Entergy has been installing transmission lines on towers that can withstand winds of up to 150 mph. The company has also raised its standards for neighborhood-level distribution poles. But Entergy wouldn’t provide a breakdown of how the newer structures fared in Ida. State lawmakers also requested that information in a September meeting. Entergy said it would provide the answers in a follow-up meeting, which hasn’t been scheduled. According to Entergy spokesperson David Freese, it generally costs about 50% more to install the new, stronger distribution poles. But in coastal areas, Entergy has to dig deeper holes and put steel caissons into the ground, which makes each pole more expensive. In the areas near where Ida made landfall, Freese said, “fewer than 1% of the more than 380 newer, more resilient structures were destroyed.”

What is the role of the Federal government?

May called the federal infrastructure bill “a start,” but pointed out the amount of money expected to come in doesn’t even compare with the amount Entergy has already spent in the past five years. May said the “frequency and intensity of storms” Louisiana is seeing requires the company to “step back and think about resiliency differently.” He also called on the feds to offset some of the costs incurred from Ida, even though historically it’s rare for the federal government to reimburse for-profit companies after disasters. If past is prologue, the billions in costs left by 2020 and 2021 hurricanes will ultimately be paid by customers. Exceptions are rare, though the feds did send $200 million to help rebuild the grid in New Orleans after Katrina, an effort aimed at avoiding huge increases in customer bills.

There is a way to get the help needed and it exist in the legislature.

Louisiana does have an important tool for reducing those costs. After Katrina and Rita hit in 2005, the Legislature enacted a process called securitization, where customers pay dollar-for-dollar costs of restoring and rebuilding the damaged parts of the grid. Instead of using the normal rate-making process, where the companies can tack on an agreed-upon profit on top of any costs, the utility issues bonds to pay for the restoration. According to the PSC, this has saved about $700 million since 2008, when it was enacted. But there may be other ways Louisiana can get help. Under the federal Stafford Act, government agencies, electric co-ops and other public entities can get reimbursed by the feds for the lion’s share of their hurricane-related costs. Investor-owned utilities like Entergy — which raked in a record nearly $1.4 billion profit last year — aren’t eligible. Entergy and its regulators are hoping to unlock more federal aid by arguing that Louisiana’s grid is of national importance. Louisiana is home to about a fifth of the nation’s oil refining capacity and is the country’s biggest exporter of liquefied natural gas. If the grid crashes after major storms, the rest of the country could feel the pain, they say.

The Feds are a non-starter for most cases.

Curt Hébert, a former Entergy New Orleans executive who later served as the chair of FERC, said he looked for ways to get federal aid “time and again” when working for Entergy. Mostly, he was unsuccessful. He said Congress should “find a way for all customers to have the ability to benefit from the Stafford Act, especially those in storm-prone areas like the Gulf South.” May said some of the eight transmission sources feeding New Orleans that failed during Ida were built to older standards, and that Entergy will need to “strategically replace” and strengthen them. He said the solution to grid-hardening is “all of the above,” including burying some lines and building the rest stronger. But it will cost money. “We have to keep in mind a very significant part of our customer base is below the poverty line,” May said. “They should not be put in a position of having to choose to pay their electrical bill or buying food, medicine, that type of thing.” Activists say Louisianans deserve a better grid, and that proactive investments, while costly up front, will ultimately save money. Advocacy groups are also calling on utility companies to shift their focus — and capital — toward renewable energy and better transmission lines, as opposed to natural gas-fired power plants. If the lights stay on during future storms, those investments could pay for themselves in the long run. Several groups have pushed for renewable micro-grids as a way to keep the lights on.

Curt Hébert, a former Entergy New Orleans executive who later served as the chair of FERC, said he looked for ways to get federal aid “time and again” when working for Entergy. Mostly, he was unsuccessful. He said Congress should “find a way for all customers to have the ability to benefit from the Stafford Act, especially those in storm-prone areas like the Gulf South.” May said some of the eight transmission sources feeding New Orleans that failed during Ida were built to older standards, and that Entergy will need to “strategically replace” and strengthen them. He said the solution to grid-hardening is “all of the above,” including burying some lines and building the rest stronger. But it will cost money. “We have to keep in mind a very significant part of our customer base is below the poverty line,” May said. “They should not be put in a position of having to choose to pay their electrical bill or buying food, medicine, that type of thing.” Activists say Louisianans deserve a better grid, and that proactive investments, while costly up front, will ultimately save money. Advocacy groups are also calling on utility companies to shift their focus — and capital — toward renewable energy and better transmission lines, as opposed to natural gas-fired power plants. If the lights stay on during future storms, those investments could pay for themselves in the long run. Several groups have pushed for renewable micro-grids as a way to keep the lights on. “The federal government is going to have to step in and help usher through this transition,” he said.

This is a dispute largely between the consumer and Entergy. Entergy has to decide on investors or the consumer and the consumer has to realize we will have to pay for something. Transparency is needed on both sides.