Google Earth

The Diversions permits from the Corps are here and they can start in March 2023.

Louisiana’s proposed $2.5 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, designed to reconnect the Mississippi River with the Barataria Basin to create as much as 21 square miles of wetlands by 2070, was awarded key permits by the Army Corps of Engineers on Monday that could allow construction to begin in March 2023. The approved environmental permits and a permit allowing the project to impact levees and shipping on the Mississippi River were announced in a news release on Monday afternoon. The “record of decision” documents include a variety of special conditions the state must comply with during and after construction. The state must measure the effects of the diversion’s operation on fisheries, including threatened and endangered species; its effect on bottlenose dolphins and on rebuilt wetlands adjacent to the diversion; and any flooding impacts the project has on local communities. It must also assure that the diversion opening does not impact shipping. Corps officials pointed out that the decision to issue permits for the project was not an endorsement of the project itself, but rather confirmation that the diversion was the least damaging of seven alternatives considered by the state, including a plan to do nothing and to allow the state’s coastline to continue to erode as climate change causes sea levels to rise. “We take great care to neither endorse nor oppose any project when administering our regulatory authorities,” said Col. Cullen Jones, commander of the Corps’ New Orleans District office, in pointing out that the Corps was asked to issue permits for a state-requested project, and not to a project actually proposed or being built by the Corps itself. “Our responsibility is to use the science, engineering, technology and data available to make the best-informed decision.” “The people that live and work in a project area know the area better than anyone,” said Maj. Gen. Diana Holland, commanding general for the Vicksburg-based Mississippi Valley Division, which includes the New Orleans district. “Their concerns and recommendations, along with that of our fellow local, state and federal cooperating agencies, were essential to our evaluation of topics such as the local environment, economics and environmental justice. Every comment received was considered and used in reaching the final decisions.”

nola.com

(Army Corps of Engineers)

All public comments are now closed and the permits were issued after reviewing them.

The permits were approved by both Jones and Holland, after additional public comments were collected on a final version of an environmental impact statement released by the Corps in April that also concluded the project’s benefits outweighed its problems. The project “represents a major step forward to restoring for injuries suffered by our coastal estuaries as a result of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill,” said Gov. John Bel Edwards in a news release after the Corps announcement. “Communities we feared could be removed from the map in 50 years will instead see thousands of acres of wetlands in the future that will provide them with natural and sustainable protection.” “Today is the most important day in the history of our state’s coastal program and represents a turning point in the story of Louisiana’s coast,” added Chip Kline, chairman of the coastal authority, which will oversee the project, and Louisiana’s representative on the Louisiana Deepwater Horizon Trustees Implementation Group, which has approved spending up to $2.25 billion to build the diversion.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

Cost increase have made the total cost by almost $2B.

Kline said the state hopes to spend only an additional $1.9 billion on construction of the project, despite recent significant increases in the cost of similar major restoration projects. “The greenlight on this project moves us closer to finally implementing a critical component of the solution to our land loss crisis that science has pointed us to for decades – using the land-building power of the Mississippi River to sustainably build and maintain land,” Kline said. “It unlocks our ability to use every tool in the toolbox, making our approach to coastal restoration and protection efforts stronger, more effective, and more innovative than ever before.” Adding his congratulations in a Monday evening Tweet was U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La.: “This is a major victory in our effort to rebuild and preserve Louisiana’s eroding coastline.” The Corps decision also was praised by the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, an organization whose members include representatives of businesses, environmental groups and residents of coastal communities. “It would be impossible to overstate the importance of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, so this is a huge moment for our entire state,” said Kim Reyher, the coalition’s executive director. “Finally, we are about to use the most important tool available to us: the mighty Mississippi.”

More congratulations came in but also some comments by those opposed.

CRCL was joined in praising the decision by other members of the Restore the Mississippi River Delta coalition, which actually conducted research into the diversion’s operation in support of the state in the early stages of the project’s consideration. “We know this decision does not come lightly—some of the best and brightest minds have contributed to its progress for decades, analyzing it from every angle. We are grateful to those who worked so diligently for so long to reach this landmark decision,” said Simone Maloz, campaign drector for the coalition. A key opponent of the project, Capt. George Ricks, president of the Save Louisiana Coalition, warned that a number of opponents, including fishers who fear their livelihoods — oyster farming and shrimp harvesting — could be destroyed by the freshwater delivered into Barataria Bay by the diversion. “Our stance has always been that this project is not good for Louisiana, especially for our tourism, our seafood industry, our communities,” Ricks, a charter boat captain, said. He pointed out that at least one potential candidate for governor, Lt. Gov. Billy Nungesser, has already called for the project to be killed.

(Army Corps of Engineers)

There is a real expectation that this decision will be taken to court.

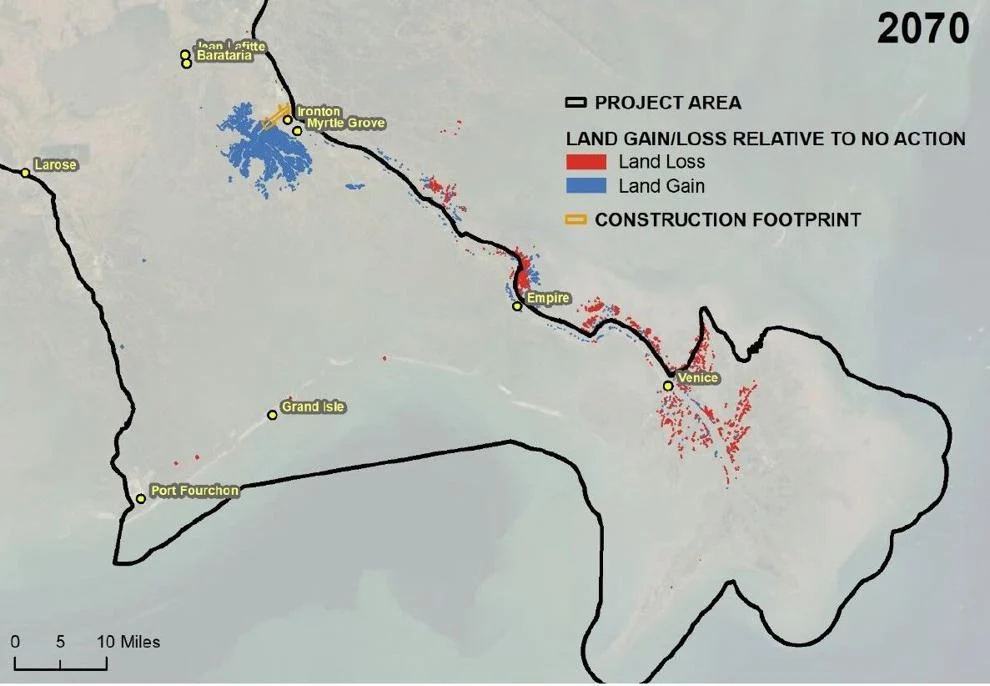

Ricks said he expects some of the opponents to challenge the Corps permits in federal court, once they have reviewed the permit restrictions placed on the state by the Corps. Any lawsuit likely would also target the diversion’s expected effects on four families of bottlenose dolphins that now call the bay their home, totaling about 2,000 individual dolphins. A final environmental impact statement on the diversion, released in April, concluded the project will provide significant future storm surge flooding reductions for New Orleans area west bank residents by creating nearly 21 square miles of new land through 2070. The statement, however, also made clear that the concerns of fishers, and of those worried about dolphins, are mostly accurate. The statement also warned that some communities in lower Plaquemines Parish will be at greater risk of high water levels when the diversion is operating.

The state has set aside money for mitigation efforts.

The state already has committed to spending $360 million on mitigation efforts aimed at both fishers and residents in danger of higher water levels as part of the project’s costs. Part of that money will increase funds available for responding to dolphin illnesses and deaths, though biologists who study Gulf Coast dolphins say there’s little the state can do to get dolphins to stay out of their home territories, where they’ll remain in danger. Mitigation efforts will include capturing endangered pallid sturgeon that move into the diversion when it’s opened and relocating them to the river. But the Corps record of decision points out that the state expects 97% of the four dolphin groups in the basin to be killed within the first year or so of its operation, and points out that the Marine Mammal Commission has said there’s no indication in the state’s mitigation plan for dolphins that guarantees a solution for that problem.

The money is from the Deepwater oil spill and that money is beginning to run out.

The diversion, to be paid for with money from funds provided by BP to mitigate natural resource damage caused by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, includes a two-mile-long concrete channel that would be built at mile marker 61 near Myrtle Grove. Gates on the river would be opened when water flows just upstream go above 450,000 cubic feet per second, with a top flow through the structure of 75,000 cfs. The gates could be open for as much as half of the year during high river years, with a flow of 5,000 cfs keeping the exit area free of blockages. The structure is designed to capture the greatest amount of sediment-carrying water moving along that part of the river, with the sediment expected to drop out in open water areas in the bay to slowly form land. Some of the sediment also will flow farther south and west and land on existing wetlands or wetlands recently built by the state using sediment pumped by pipeline directly from the river’s bottom. Nutrients in the river’s water also are expected to help nourish the existing and new wetlands.

There may be some loss of land.

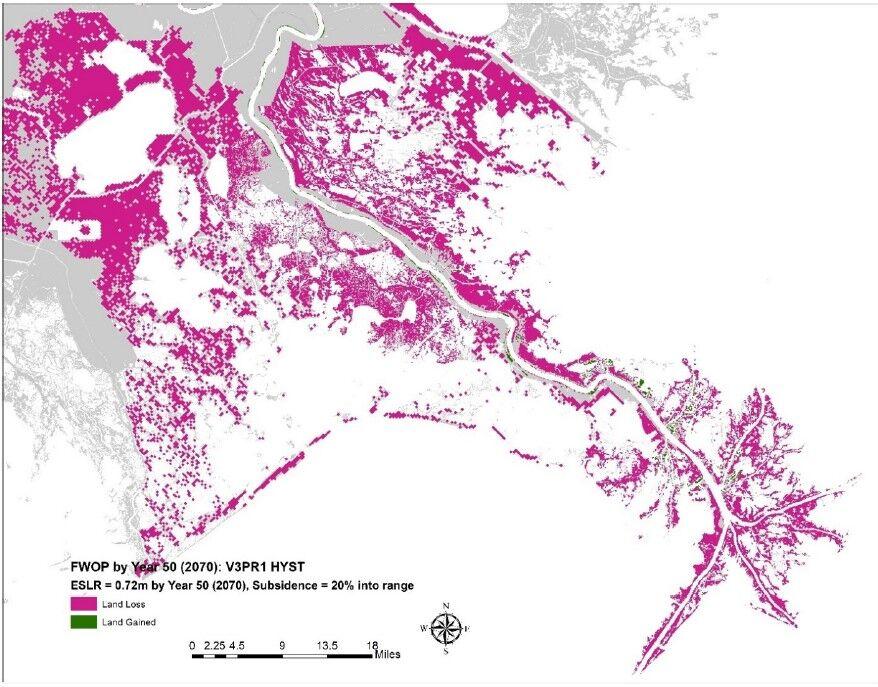

In addition to the effects on fisheries, dolphins and potential flood risks, the diverted sediment will likely cause a reduction in the size of wetlands in the birdfoot delta at the river’s mouth, with as much as 4.7 square miles lost by 2070. Officials also point out that even with the diversion and the new pipeline-fed wetlands projects being built by the state, the total amount of land in the Barataria Basin is expected to continue to rapidly drop by 2070 because of climate-induced sea level rise. But in 2070, the land created by the diversion will represent 25 percent of all wetlands left in the basin. Mitigation projects planned for areas that could be affected by water rises of as much as 1.1 feet – including Happy Jack, Lake Hermitage, Suzie Bayou, Woodpark and Grand Bayou – will include raising of roads and access points, docks and piers, sewage system improvements and some voluntary buyouts. The Myrtle Grove community will also see construction of a new community bulkhead.

Mitigation efforts will try to offset the loss of wildlife and jobs associated with them.

Mitigation aimed at fishers, including shoreside facilities, include gear improvements, refrigeration equipment and assistance in buying larger boats. Assistance for oyster growers includes expanded funding for alternative elevated oyster culture projects, new public seed grounds, and improving existing public and private oyster grounds and finding new oyster growing areas. The authority has estimated the diversion will create 12,000 direct and indirect jobs in southeast Louisiana, mostly in Plaquemines, St. Bernard, Jefferson and Orleans parishes, and will also result in $1 billion in increased sales and $650 million in additional household earnings.

I have found over life that good projects seldom totally live up to expectations but likewise bad projects never are as bad as feared. I offer that to those who oppose.