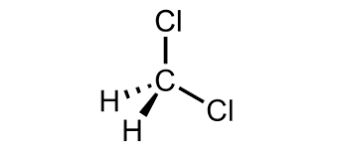

Paint strippers is were you. probably encountered methylene chloride.

The Biden administration is proposing a widespread ban on a toxic chemical used in paint strippers that has been linked to dozens of accidental deaths, the first of several long-awaited moves planned for this year to bolster the country’s chemical-safety rules. The Environmental Protection Agency said Thursday its plan would ban methylene chloride for all consumer use and most industrial and commercial uses. EPA officials say that would go much further than past efforts, though it falls short of a total ban some health groups have called for in the past. The last rule on methylene chloride — approved under the Trump administration in 2019 — had banned only consumer paint remover uses, giving wide exceptions elsewhere. This new proposal would allow only limited use in industrial manufacturing and processing, especially the production of other chemicals.

washingtonp[ost.com

Bathrooms are the usual space for this chemical.

Methylene chloride is a solvent often used to refinish bathtubs and other surfaces, and to make pharmaceuticals and refrigerants. Short-term exposure can cause dizziness, headaches and harm the central nervous system, and long-term exposure can be toxic to the liver and cause cancer. The EPA says it is especially risky to home renovators, even trained workers in protective gear. Despite such risks, the chemical’s use has continued because of its popularity with the military and,also, its use in newer coolants developed to replace some types of hydrofluorocarbons, among the most potent contributors to climate change. The EPA proposal would give leniency for methylene chloride’s continued use by the Defense Department — among other federal agencies — and makers of more climate-friendly coolants, the agency said. The agency has been under pressure to issue new rules like this under Congress’s 2016 overhaul of the Toxic Substances Control Act. This is only the EPA’s second proposal in the eight years since. Lobbyists and agency officials have said to expect four to seven more this year, plus a potentially completed rule banning one of the last actively used forms of asbestos, the only other proposal EPA has issued under the law. “The science on methylene chloride is clear, exposure can lead to severe health impacts and even death, a reality for far too many families who have lost loved ones due to acute poisoning,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said in a statement. “This historic proposed ban demonstrates significant progress in our work to implement new chemical safety protections and take long-overdue actions to better protect public health.”

Safety advocates say thanks but we need to do more.

Many safety advocates lauded the agency for making progress but also said it should do more. The environmental law firm Earthjustice, which helped lead a lawsuit over the Trump administration’s rules, said it will push the agency to produce a final rule with narrower exemptions and work to make them as short-lived as possible. “This proposal is a win for public health, and a tribute to the workers, families, and other advocates,” Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz, a senior attorney with the group, said in a statement. “But exemptions in the rule would allow certain uses of methylene chloride to continue for a decade or more, leaving workers, service members, and communities at risk.” But the agency is also getting some support from safety advocates who had expressed disappointment with the more lenient rule. Wendy Hartley, whose 21-year-old son, Kevin, died in 2017 while refinishing a bathtub — even after being trained in how to apply the paint stripper — lauded the proposal in a statement provided to the EPA. “No mother should have to face that,” Hartley said of her son’s death. “The EPA is proposing to ban its use as a commercial bathtub stripper once and for all, and I urge the agency to quickly finalize the rule and make sure no other mother has to go through what I did.”

Home renovation is where most of the deaths have occurred.

Since 1980, the EPA said, at least 85 people died from acute exposure to methylene chloride. Most of them were workers in home renovation. That has made the solvent a top target for regulators. It was among the first 10 chemicals designated for evaluation under the 2016 law — the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act. The EPA proposed an outright ban on Jan. 19, 2017, the day before President Barack Obama left office, saying it posed “unreasonable risks” to human health. But the agency in 2019 retreated from that decision under pressure from the Pentagon, proposing to allow commercial operators to keep using the chemical so long as they are trained. For uses still allowed under the new proposal, the EPA would apply “strict exposure limits,” the agency said. It would allow limited uses of methylene chloride by the Defense Department, NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration with strict controls, the agency said, because their “highly sophisticated environments” can reduce worker exposure and minimize their risks. Data provided by those government agencies and companies gave EPA officials confidence that they can protect workers, Michal Freedhoff, head of the EPA’s chemical safety and pollution prevention, said in a call with reporters. “Every single time, when we allowed either an exemption from a ban or continued use of a particular application of methylene chloride, it was accompanied by [an] extremely strong safety protection program,” she said. “We did trust that a large, sophisticated chemical company would be able to implement the engineering, monitoring and [protective gear] requirements that our rule requires.”

A ban should be in junction with a safety program.

The American Chemistry Council, which represents chemical manufacturers, said the rule could overlap with other existing federal safety regulations. It also noted an EPA estimate that the proposal would block what now amounts to more than half of the country’s annual use of methylene chloride, which it said would be a challenge, given the agency’s timeline. “That scale of reduction in production, that rapidly, could have substantial supply chain impacts if manufacturers have contractual obligations they need to follow through on or if manufacturers decide to cease production entirely,” the group said in a statement. It added there could be ripple effects, including on “pharmaceutical supply chains and the specific safety-critical, corrosion-sensitive critical uses identified by EPA.” The proposed phase-down for consumer uses and most industrial and commercial uses would be fully implemented in 15 months,the EPA said. That would come after the rule is completed — a process that usually takes several months. The next step for the agency is to publish the proposal in the federal register, opening it to 60 days of public comment.

There are more regulations coming up.

The agency has five more proposals to come soon, Freedhoff said. That includes the likely next up, perchloroethylene, a solvent used for cleaning and degreasing, and carbon tetrachloride, another solvent that is commonly used to produce other chemicals such as refrigerants. Those proposals are more likely to be similar to the partial ban proposed for methylene chloride than the full ban proposed for white asbestos, Freedhoff said.

It has to work to be that powerful! I haven’t stripped much but when I had it was in an open area.