https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery

The history of the Mississippi is being uncovered on its use in the save economy.

he names on the marble memorial outside BASF’s administrative headquarters in Geismar only hint at the people who once lived in this part of the Mississippi River corridor: Baptiste, Old Ned, Massounda, and Harriet and infant. Catalogued in old mortgage papers as the chattel property they were considered in life, they are among the 300 enslaved people known only by their first names or a generic description who lived and worked on the plantation now home to BASF, one of Louisiana’s largest chemical complexes and a major employer in Ascension Parish. After an extensive archaeological, records and genealogical search that included reaching out to descendants, BASF officials said they found the graves of about two-thirds of Linwood Plantation’s slaves a few years ago.

nola.com

The years have not been kind to these unmarked graves.

The graves were under a gravel parking lot next to a long-known mound where the plantation owners’ graves were located and next to a large pipeline rack deep inside the production zone of the 2,600-acre complex on the Mississippi. Made public and memorialized in April 2022, the discovery is one of several river sites known or suspected of having slave graves that have emerged in the past decade, as the pressure to develop new agricultural sites for industry and reevaluations of existing operations’ land bumps up against Louisiana’s painful history of slavery.At the Bonnet Carré Spillway in the 1980s, at the Shell Oil refinery in Convent in the early 2010s or the site of a proposed Formosa Plastics complex in 2019, the rich earth along the Mississippi hasn’t forgotten its past.

Hydrogen is replacing sugar cane.

The latest example comes amid another fight over industrial growth in the river region between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. In October 2021, state officials announced that Air Products would be building a $4.5 billion blue hydrogen plant in the Darrow/Burnside area of Ascension Parish. The plant, however, has drawn fire, in part because it plans to pump 5.5 million tons of carbon dioxide per year under Lake Maurepas to cut its carbon emissions. Earthjustice, a San Francisco, California, environmental group that has been active in challenging Louisiana’s river region projects, announced earlier this month that Air Products was investigating the potential of slave graves on part of the former Orange Grove plantation. Drawing Earthjustice’s attention were emails obtained from the State Historic Preservation Office. Dated from late last fall, the emails indicate Air Products was investigating the possibility of graves outside an existing, 1-acre cemetery that had already been fenced off on its 377-acre property between River Road and La. 22. The company’s archaeologist had found stones scattered just north of the cemetery, which was likely for the plantation’s owners; he told the state archaeologist at the time the stones “resembled cemetery markers.” The stones were inside of and a few hundred feet outside of a 100-foot buffer a previous archaeological investigation in 2014 had recommended around the cemetery, emails and other documents provided by Earthjustice show.

Slaves were often buried near the owners.

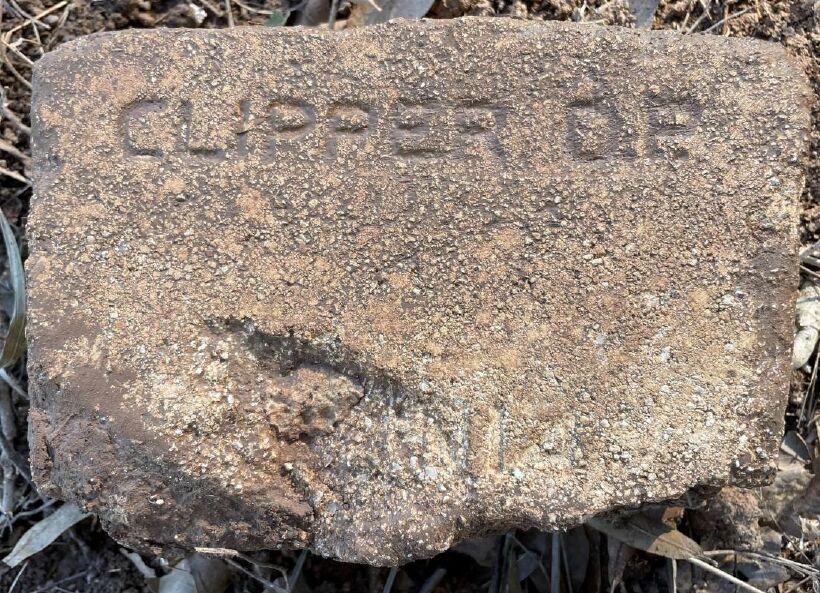

As at BASF, slaves were often buried near their owners, but Air Products officials said their archaeological investigation, which was done in cooperation with the State Historic Preservation Office and included the use of ground-penetrating radar, didn’t find graves in the buffer. “Out of respect for the cultural resources of Louisiana and in accordance with applicable law, Air Products conducted an extensive archaeological survey and historical research of the proposed project area and found no evidence of unmarked burials outside of the boundary of the Orange Grove Cemetery,” the company said in a statement. Air Products’ research has determined that the stones were high-temperature bricks probably used in kilns at the former Ormet alumina complex next door. The bricks were likely discarded in construction and later moved around when fields were plowed, the company says.

Provided by Air Products

There were graves, but where?

Chip McGimsey, the state archaeologist, visited the site in December and said he didn’t believe, based on his experience, that the stones would turn out to be grave markers. He noted old maps don’t indicate another old cemetery or clump of trees that might suggest a cemetery at Orange Grove, though one might be expected. In a state that had one of the highest concentrations of slaves in the nation in 1860, the river region had among highest concentrations in Louisiana. Large, labor-intensive farms like ones growing sugar cane demanded significant slave workforces, experts say. Ascension Parish had unusually large slave workforces, according to the 2003 book “American Slavery.” Half of all slaves in Ascension lived on plantations with 175 slaves or more. Citing federal census tallies, Earthjustice noted that the owner of Orange Grove, John Burnside, had 753 slaves in 1860, the largest of any in the parish at the time. “There’s just almost an automatic that some of the slaves and/or the young children are going to die during the time the plantation is in operation,” McGimsey said, “and there will be a cemetery somewhere, but those never made it into the records.” Corinne Van Dalen, a senior attorney with Earthjustice, said Air Products has a moral obligation to do a gold standard investigation that goes beyond the boundaries of the existing cemetery. “So the question that remains is where is the cemetery for those who were enslaved on Air Products’ site,” she said. “The company has not answered that question.” McGimsey said Air Products has looked at least at one other part of the site where a suspected and potentially historically significant sugar mill may have been located. Air Products says it is finalizing a report of its investigation for the State Historic Preservation Office, and its construction plans will honor the 100-foot cemetery buffer, disputing claims to the contrary.

You need to reach out to the public and the Decedents Project.

In a statement, Earthjustice also faulted Air Products for not notifying the public about its investigation of its property or reaching out to the descendant community. The Formosa Plastics complex in St. James Parish, which remains tied up in legal and regulatory challenges, drew similar criticism after advocates learned more about the company’s research into cemeteries on that property. A small part of the site has been marked off, though the company says it isn’t sure who is buried there. McGimsey said Air Products likely won’t be obligated by law to notify the public until it seeks a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers wetlands permit. Corps officials said none has been sought so far. Citing the ongoing issue in the river region he represents, Congressman Troy Carter, D-New Orleans, asked the U.S. departments of Environmental Protection and Interior last month to require industries seeking permits certify that sites don’t have the graves of the formerly enslaved. Carter said he wants to develop a process to ensure cemeteries are found and memorialized and suggested that Air Products and other companies facing pushback to engage the public and even find an outside party check their findings. “Because having public confidence is very important, having neighborhood buy-in is very important and making sure that we’re demonstrating that these companies are willing to be good neighbors,” he said.

This was not quick and simple research.

Complicating the research process, dead bodies buried 150 to 200 years ago in Louisiana’s climate and soils don’t often survive but can be marked by the underground discoloration of the earth, nails left from old coffins and other artifacts. The public and descendant community can lend insight into where grave sites might be to narrow down the search. Kathe Hambrick, founder of the River Road African American Museum and of a burial grounds coalition, played an important role in researching burial sites at BASF and at Shell in Convent and said she has identified other cemeteries in the region. Shell began investigating its property near Convent as it eyed plans for an expansion. BASF officials say they stumbled into its discoveries after initially setting out simply to improve the maintenance of the burial mound, later discovered to a Houmas Indian site more than 1,000 years old. They soon reached out to Hambrick and consultants associated with her to check their findings, to reach out descendants, and to develop better understanding of the property’s history, company officials said. “We brought them in at the end of 2020 once we sort of made our discoveries,” said Blythe Bellows Lamonica, BASF’s spokeswoman.

Sometimes the residents don’t respond.

Hambrick said she has been reaching out to the various owners of Orange Grove for 25 years and hasn’t been able to get a response. Today, burials sites at both the Shell and BASF plants have been marked and have memorials honoring the dead. BASF’s memorial is away from the graves outside the production zone and includes the Sankofa, a West African symbol usually depicting either a stylized heart shape or a bird with its head facing backward and holding an egg in its mouth. Hambrick recommended the memorial use the symbol, which emphasizes the need to learn from the past and comes from a part of Africa from which many Louisiana slaves were taken.

We need to earn our history, the good and bad.