The EPA holds a hearing and both sides got to talk. one is rosy on carbon capture and the other is wary.

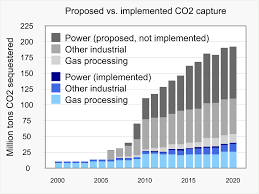

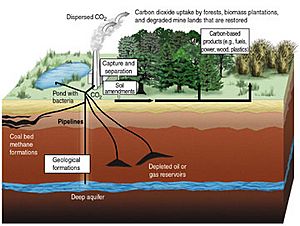

Louisiana’s ability to regulate carbon capture injection wells went before the court of public opinion Wednesday as proponents and critics of the burgeoning industry sparred at the first day of a three-day public comment marathon on the state’s bid to wrest control of the wells from the federal government. At a lengthy public hearing at the LaSalle Building in downtown Baton Rouge, critics took aim at the state Department of Natural Resources’ ability to oversee the wells safely and efficiently, while industry advocates said shifting control to Louisiana will lead to an economic and environmental boon for the state. At the center of the debate is DNR’s request to gain “primacy,” or direct regulatory control, of Class VI wells, which are used to inject carbon dioxide into deep underground rock formations. The wells are a key piece of carbon capture, an increasingly popular method to curb carbon dioxide emissions amid global efforts to fight climate change. The Environmental Protection Agency oversees the vast majority of permitting for Class VI wells. Wyoming and North Dakota are the only states that directly regulate the wells.

nola.com

State primacy speeds up the process.

Louisiana first applied for primacy in 2021 in an effort to speed up carbon capture well reviews. The EPA announced in April it would take public comments on the request through July 3, though the agency has said the state’s formal application has met the technical requirements for approval. DNR spokesman Patrick Courreges said state officials are hopeful the EPA could rule on the primacy application by the end of the year. Gov. John Bel Edwards and industry advocates have championed carbon capture as an economic driver and a greenhouse gas restrictor. However, critics have questioned the technology’s effectiveness and safety. Pushback against a proposed well in Livingston Parish led to a slew of bills attempting to curb carbon capture, though most of those bills failed amid industry pushback. Gov. John Bel Edwards and industry advocates have championed carbon capture as an economic driver and a greenhouse gas restrictor. However, critics have questioned the technology’s effectiveness and safety. Pushback against a proposed well in Livingston Parish led to a slew of bills attempting to curb carbon capture, though most of those bills failed amid industry pushback. Jockeying began before Wednesday’s hearing started. Industry supporters camped out under a tent near the LaSalle Building to preach the benefits of carbon capture, while environmental justice groups held a media session at a coffee shop a block away. More than 17,800 public comments have been submitted online, and the agenda for Wednesday’s session listed more than 100 potential speakers. However, about 30 people stepped up to the microphone. Additional sessions are slated for Thursday and Friday.

Does carbon capture lock us into fossil fuels?

Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, said carbon capture is an attempt by industry to “push us back and lock us into the continued burning of dirty energy.” Wright expressed fears over possible groundwater contamination and accidental leaks when carbon dioxide is transported. She said DNR’s request failed to consider the disproportionate impact of industry on minority, indigenous and poor communities. “Who wants a future that repeats the past of leaking and broken-down oil and gas wells that are abandoned by companies?” Wright said. Tommy Faucheux, president of the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, said primacy would let the state “quickly and safely” implement the latest carbon capture technologies. He argued the U.S. has safely operated carbon capture for more than 50 years. “Louisiana knows its geology best and should be empowered to make decisions for its energy future,” he said. Faucheux said carbon capture is a viable pathway to the state’s net zero emissions goals, as well as a driver of good jobs. He said Louisiana is years ahead of other states for carbon capture investments. “We are seeing opportunities for hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of jobs to come to this state as a result,” he said.

The comments continued.

Logan Burke, executive director of the Alliance for Affordable Energy, called the regulatory transfer a “threat to our future and safety,” in part because of the anticipated speed with which the state could approve new wells. Burke said the EPA has only permitted two Class VI wells nationwide. Meanwhile, North Dakota has already permitted five. “Industry is waiting for the famously under-resourced and permissive DNR to have the authority to hand out permits,” she said. Courreges acknowledged DNR had issues with oversight decades ago. However, he said the agency has made strides in recent years, particularly under Edwards. DNR is also planning to hire 70 new staffers dedicated solely to Class VI well regulation, Courreges said. Primacy would make Louisiana a leader in energy innovation, said Marc Ehrhardt, executive director of the Grow Louisiana Coalition, an energy industry advocacy organization. He argued the state’s industrial sector has reduced its air emissions by 75% in the last three decades while increasing production. “We can make deliberate, positive change safely now if Louisiana can decide its own future when it comes to Class VI wells,” Ehrhardt said.

Environmental groups against industry, as usual.

Darryl Malek-Wiley, a senior field representative for the Sierra Club, argued the EPA needs to restart its review of DNR’s primacy application because of House Bill 571, legislation signed by Edwards that outlines the Class VI well process in Louisiana. “The whole process needs to be reset,” Malek-Wiley said. Mark Miller, a board member of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association and president of Merlin Oil and Gas Inc. in Lafayette, said primacy would help relieve the EPA’s administrative burden without completely removing the agency’s oversight. “We believe primacy and carbon capture make good sense for Louisiana,” Miller said. Outside of industry lobbyists, some residents voiced support for Louisiana’s primacy effort. Steven Braud, owner of 4B Plastics in Baton Rouge, said carbon capture could help boost crude oil production, which in turn would help his business and the state. “You have a chance to positively impact the state and generations to come,” Braud told EPA officials. Others spoke against it. Justin Solet, a member of the United Houma Nation tribe, said carbon capture projects in south Louisiana could lead to coastal and wetland damage that could lead to a “forced mass exodus” of residents. “The Gulf is not a sacrifice zone to be used by industry,” Solet said.