None of the republican representatives nor Senator Kennedy voted for the Infrastructure Bill that will help Louisiana. One of the ways the help is given is to Lake Pontchartrain.

The ecological health of the 5,000-square-mile Lake Pontchartrain Basin will be the focus of $53 million in grants in the federal infrastructure bill that President Joe Biden plans to sign Monday. About $10.5 million will be distributed annually over the next five years by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for a variety of programs aimed at improving water quality and restoring fish and wildlife habitat. That’s as much as 10 times what EPA annually provides for the basin. “To go from $1 million to $2 million a year to $10 million a year, that’s a lot of money,” said Kristi Trail, executive director of the Pontchartrain Conservancy, which is likely to receive a significant share of the money. “The amount is what we dreamed of 20 years ago,” said Trail’s predecessor, Carlton Dufrechou, who led the agency when it was called the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation. Dufrechou is now executive director of the Causeway Commission. The conservancy has been pushing for more financial support since its inception in 1989, and was instrumental in getting then-U.S. Sen. David Vitter, R-La., to sponsor legislation that created the EPA basin restoration program in 2000.

nola.com

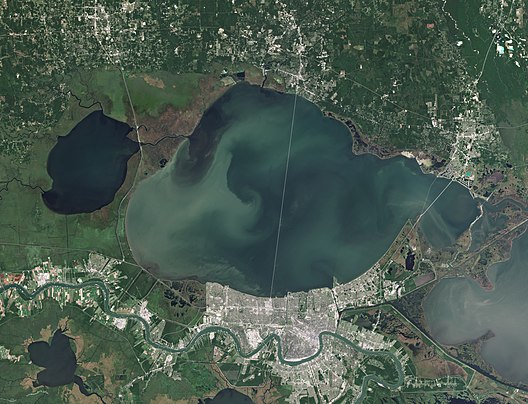

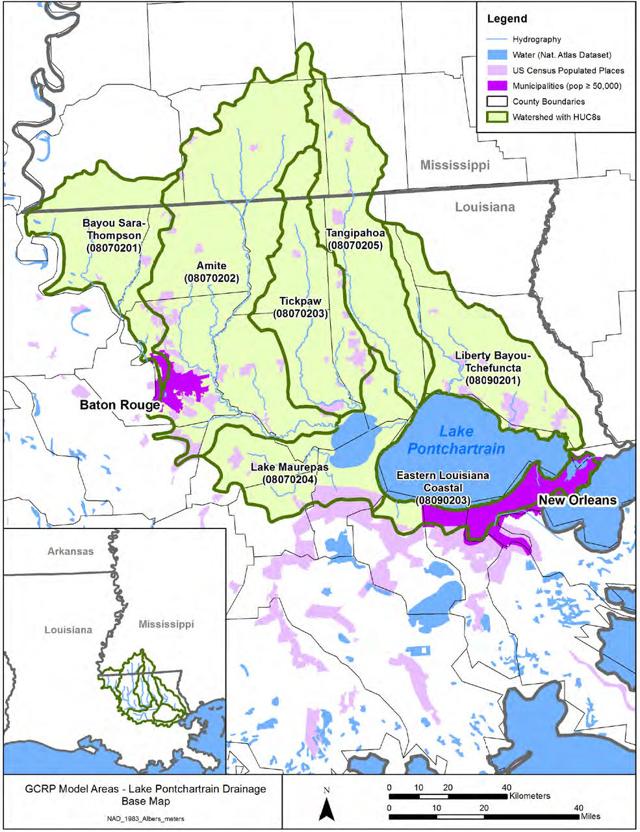

You can see all of the runoff that feeds the lake. It is a large area with farming and other activities that have pollution capabilities.

Most of the basin’s water quality problems result from “nonpoint source” pollution: Sewage-related runoff, from both human and wildlife sources, within the watersheds of five north shore and River Parishes streams and bayous and drainage water entering Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans, Jefferson Parish and other south shore communities. A 2020 inventory by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality found that only 27% of water areas in the basin was fully supportive of fish and wildlife propagation, meaning the rest was impaired for aquatic habitat, food, resting, reproduction, cover or travel corridors for fish and wildlife, and could pose contamination problems for fish caught and eaten by residents. The inventory found that only 51% of the area was fully supportive of primary contact recreation, which includes swimming, water skiing and underwater diving, in part because of the risk of ingesting contaminated water. However, 96% of the water courses were considered supportive of secondary contact recreation, which includes fishing or boating when regular, full-body contact with contaminated water is not likely. On the north shore and in the River Parishes, the key issues are contaminants from leaking pipes and equipment in community sewage collection and treatment systems, and improperly operated individual residential sewage treatment systems, modern versions of what used to be called septic tanks.

As noted, the basin covers a large part of the state.

The basin includes parts of 16 parishes from just south of Baton Rouge to the Mississippi state line. It encompasses lakes Pontchartrain, Maurepas and Borgne, and adjacent wetlands in New Orleans East and St. Bernard Parish. The EPA lake restoration program was first funded in 2002. It followed major efforts by New Orleans area environmental activists aimed at improving Lake Pontchartrain’s water quality, which resulted in the creation of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation in 1989. That same year, the state banned lake bottom dredging of Rangia clamshells, which were used in road building. The dredging made the water to too cloudy for submerged aquatic vegetation to grow and made the sediment so soft that baby clams sank into the muck and were smothered. The Pontchartrain Conservancy has used money from the EPA restoration program to support its weekly water monitoring program, and has used money from that and other EPA programs to target water improvement projects throughout the basin, including an early successful program of rebuilding manure waste ponds at north shore dairy cattle farms. Money from the program may also be used to support habitat restoration projects proposed under Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan for hurricane protection and restoration. Some of the money from the program was used to help restore marsh on the south shore at Bucktown.

The Maurepas Land Bridge will probably be a specific action of the bill’s money.

One possible target of the new infrastructure bill money is protecting the Maurepas land bridge at Manchac, which experienced significantly eroded during Hurricane Ida and is threatened by future sea level rise caused by global warming. “Just imagine if that land bridge wasn’t there and all that [Ida surge] water surged into Lake Maurepas, how much flooding communities even as far north as Baton Rouge would have seen,” Trail said. Another target could be a better understanding of the effects of Mississippi River freshwater funneled through the Bonnet Carre Spillway into the basin during high river periods. In some years, such as 2019, so much freshwater ran through Lake Pontchartrain into saltier Lake Borgne and the Mississippi Sound that it killed oysters, and nutrients in the water created algae blooms that forced closure of beaches on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The grant money will continue to be distributed by the University of New Orleans Research and Technology Foundation, which has been EPA’s conduit for the program since 2002. For individual projects, applicants must pay 25% of the cost. Grant requests will be reviewed for their potential effectiveness first by a committee of experts set up by the UNO Foundation and then by EPA. The projects are supposed to be in line with a comprehensive management plan for the lake, first written in 1989 and been updated every five years.

A bill to help the state and they voted no. But I bet they will take credit for it! Since Lake Pontchartrain is in Rep Scalise’s district he should have had a loud yes for the vote as on his website he lauds other construction in Houma and other sites.