The first two hurricanes are being tracked already. One is in the Atlantic and no threat to us the other is in the Gulf and looking at maybe the

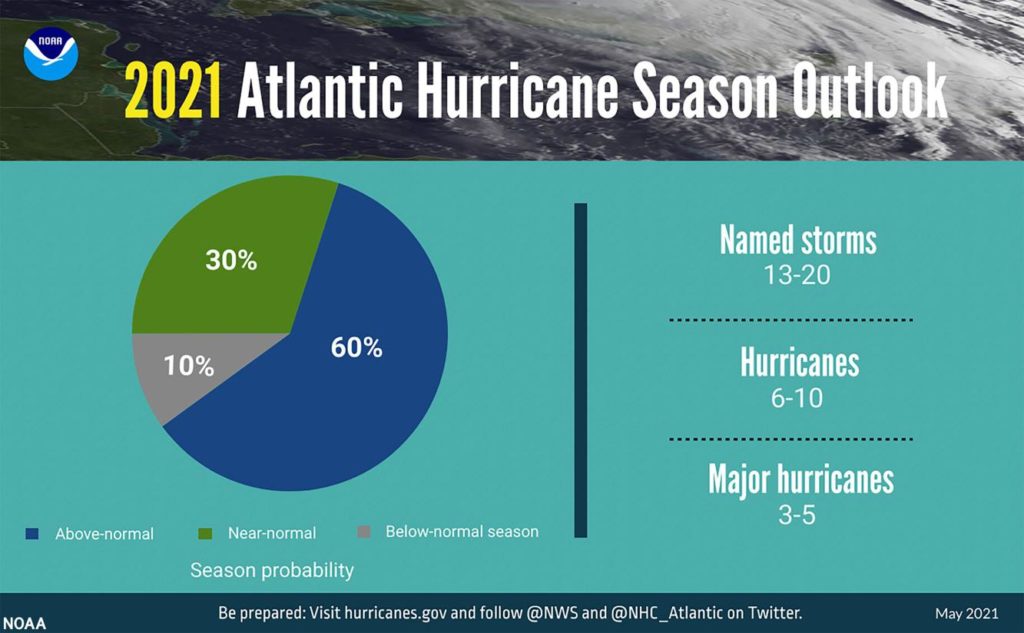

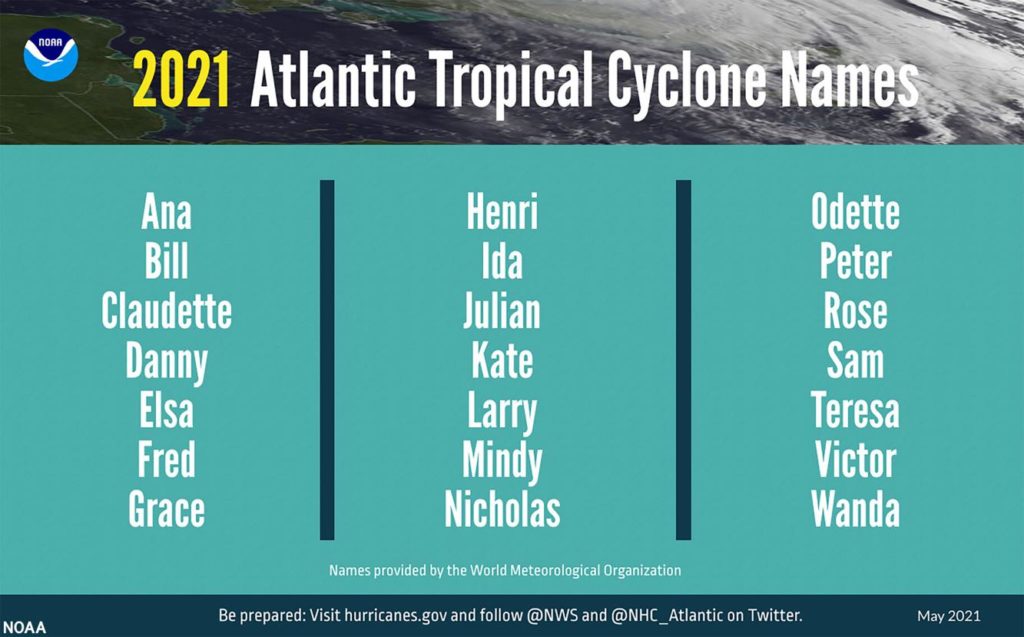

Lake Charles area, again. What to expect? 13-20 named storms (at least that is the alphabet) with 6-10 being hurricanes and 3-5 being major ones.

Matthew Rosencrans, lead seasonal forecaster for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said there’s a 60% chance of a more-active-than-normal season, a 30% chance of a near-normal season and only a 10% chance of a below-normal season. If accurate, this will be a record-setting sixth consecutive year with an above normal number of tropical events, even after the agency raised its averages for storms in a normal season. And it follows the record-breaking 2020 season of with 30 named storms, with 13 of those making landfall in the United States – including six hurricanes. The previous record was in 2005, which saw 28 named storms, including hurricanes Katrina and Rita striking Louisiana. The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 through Nov. 30.

nola.com

This season also includes the present eastern Pacific El Nino-La Nina neutral warm water conditions which will have cooler La Nina conditions in the late summer. THis means less storm shear conditions.

“Predicted warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds and an enhanced west African monsoon will likely be factors in this year’s overall activity,” he said. Rosencrans said the effects of human-caused global warming might also play a small role in formation and intensity of 2021 storms. Climate effects have resulted in more rainfall during individual storms and increases in intensity that have recently resulted in more storms reaching Category 4 and 5 strength.

Climate effects also mean more will begin and start further north making the East Coast and mid-East Coast and up more in danger.

The 2020 season was especially damaging to Louisiana, which saw five named storms make landfall, including the one-two punch of Category 4 Laura and Category 2 Delta in Lake Charles, as well as Category 3 Zeta in the New Orleans area. This year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began using 1991-2020 as its 30-year period of record for tropical events in the Atlantic basin, which increased the historic averages to 14 named storms and 7 hurricanes. The average for major hurricanes remained unchanged at 3. The previous averages were 12 named storms and 6 hurricanes. In April, climatologists at Colorado State University forecast that the 2021 Atlantic season will have 17 named storms, including 8 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. That forecast also said there was a 44% chance of at least one major hurricane making landfall somewhere along the Gulf Coast from the Florida panhandle westward to Brownsville, Texas. The average for such a landfall over the past century is 30 percent.

There is not a prediction for Louisiana and National Hurricane Center Director Ken Graham advises Lake Charles, which was hit hard late year and just flooded, to take care.

“It’s about having as much of that work wrapped up as possible, and you also have to be ready to go,” said Graham, who ran the Slidell office of the National Weather Service before becoming the hurricane center director in 2018. “If we have another strong system and there’s calls for an evacuation by emergency management and local elected officials, you’re going to have to have that family plan in place and know where to go.” The message is the same for New Orleans area residents, who have not had to evacuate en masse since Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008, he said. “It’s about preparing every single year as if you’re going to be hit,” he said. “Because the stress level is intense when a storm is headed you’re way. You’re watching everything, listening, and it’s very stressful. But if you have all that in place and ready to go, the stress levels go way down.”

Michael Brennan, who oversees the hurricane specialists at National Hurricane Center, said Louisiana did pay attention last year with the number that hit us but we need to keep that up as Laura showed the damage that can occur.

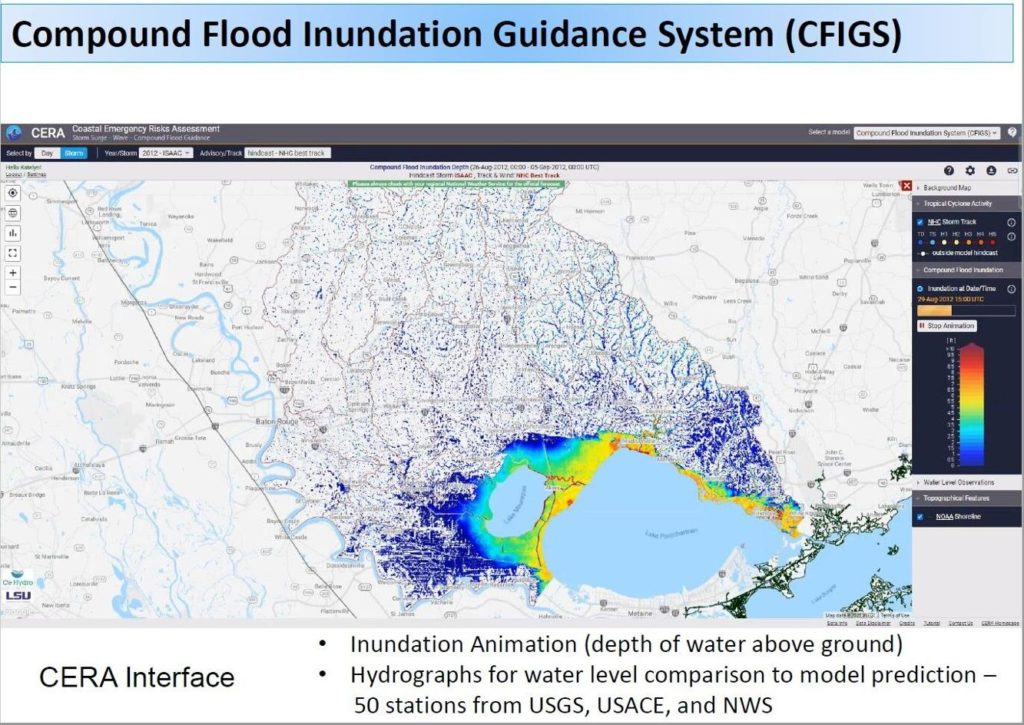

“We’re having fewer direct fatalities from the surge and the wind, but we lost 16 people to carbon monoxide poisoning after the storm,” he said, with other deaths resulting from cardiovascular stress, heat and accidents. “People are left in a very vulnerable situation after a significant storm like that in an area where they may not have access to medical care or emergency services or water or power, and that could be deadly,” Brennan said. “Those indirect deaths disproportionately affect the older population, 60 and over, and that’s something we need to focus on. Graham said improvements in the hurricane’s center’s storm surge forecast modeling could result in surge warnings being issued 60 hours in advance of landfall for some storms this year, instead of 48 hours as in the past few years. The model has been improved to understand the large size of a hurricane and its effects on surge heights and direction, such as occurred with Hurricane Isaac in Louisiana in 2012. “It wasn’t very strong, as far as intensity, but it was large and moving slow, and in some areas, it created 14 feet of storm surge, though barely a Category 1,” Graham said.

He said the extended hours of warning will be used only for storms with tracks are not jumping around from forecast to forecast.

The state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, Louisiana State University and the University of North Carolina have also added a new forecasting tool to those used by emergency managers and levee officials in determining water threats in the New Orleans region. It’s designed to detect flooding effects of the type that LaPlace experienced during Isaac. The tool is a computer model that combines rainfall, storm surge and wave information in lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain to produce color-coded maps showing above-ground level water heights in areas surrounding the lakes. Conventional surge models, such as the one the hurricane center uses, do not take into account rainfall, which often results in higher water levels along streams and portions of lakes with timing different from surge effects.

This new model will be used both for evacuations and to determine when flood gates should be closed and pumping to start. There is also work between the parties to determine what surge does as it moves up the Mississippi when the river is low. This year the river will be above 10 feet so these low conditions will not be a problem.

In short, we need to remain attentive and pay attention to the warnings we receive.