The Irish Channel has fumes, noxious fumes, and not from garbage! That, at least would be a clear source and more easily fixed.

Justin Vittitow and his wife knew the blue and purple house on Magazine Street in New Orleans’ Irish Channel was a fixer-upper when they bought it 11 years ago. They’ve invested thousands of dollars in it, whittling away at a laundry list of improvements. For most of that time, air quality wasn’t a problem. It wasn’t until 2019, almost two years after his daughter’s birth, that odors began to waft toward his house and others in the neighborhood, bringing burning eyes and nostrils and causing headaches. “This is supposed to be our forever home that we renovate until our old age,” said Vittitow, a musician. But the periodic invasion of what he describes as the smell of burning tar or asphalt has put that future in question. Over the past two years, about 150 households have registered more than 850 complaints with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, which identified as a possible source a bulk liquid storage and transport complex known as BWC Harvey, across the Mississippi River in Harvey. About 7,000 people live within a 1-mile radius of the complex, and there are four other similar facilities in close proximity.

nola.com

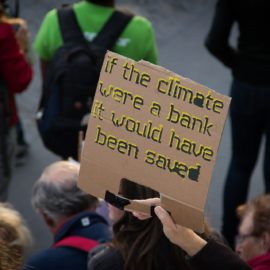

Homeowners have linked up with others and appealed to the EPA.

Vittitow and several other Irish Channel and Harvey residents banded together in the Jefferson, Orleans, Irish Channel Neighbors for Clean Air coalition to fight pollution they fear could be harming their health. They released a report alleging permit discrepancies and calling on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to scrutinize the process. On Thursday, the New Orleans City Council unanimously backed those calls with a resolution asking Gov. John Bel Edwards and the EPA to compel the state environmental agency to suspend BWC Harvey’s pollution permit for review. “We don’t know if it’s toxic, but one thing we do know that it is certainly noxious. That in itself is something that people should not have to deal with,” said council member Jay Banks, whose district includes the Irish Channel and who co-sponsored the resolution with Kristin Gisleson Palmer. “You pay taxes, you can’t be in your own house – there’s a problem with that. So, we’ve got to get this figured out as to where exactly it’s coming from and have them take whatever steps is necessary to stop it from happening.”

BWC Harvey lies just across the river from the Irish Channel and on the river in Harvey so it impacts both depending on the wind.

BWC Harvey, formerly known as Blackwater Midstream, hosts 53 storage tanks on site. An expansion permitted in 2019 added 12 tanks capable of storing 34 million gallons of material. The terminal has operated since 2015, storing and exporting products such as asphalt, distillates, caustic soda and different types of oils. Headquartered in Houston, the company’s leadership has maintained that it isn’t responsible for the fumes, but the company installed an odor-control system in response to the complaints. While the control system captures much of the stink, residents say it still allows emissions to escape. Instead of tar, Vittitow said, sometimes an unnatural smell similar to dryer sheets fills the air. “The odor control does not work. We know it doesn’t work because we’re still getting hit by this, and even if it did work, it is just another thing to placate us because actually does not make these chemicals any less dangerous,” he said. “It just hides them. It’s a masking, not an elimination.”

The BWC General manager maintains that all the facts are not being brought to bear and is not happy with the City Council.

At Thursday’s City Council meeting, Adam Smith, BWC Terminals’ senior vice president of operations, said he was disappointed with the resolution, adding that “none of the facts are being considered.” “We agree with accountability and regulation and we readily accept it, but we also believe that standards of accountability should apply to those who make allegations that are not validated by science,” he said. Greg Langley, a spokesman for the state environmental department, said agency staff have never experienced the same odor reported by the complaints. The agency also hasn’t recorded harmful levels of pollutants with handheld monitors, finding no violations by BWC Terminals. The agency has installed a new real-time air monitor on Tchoupitoulas Street to measure some pollutants, including volatile organic compounds. It is also in talks with City Hall about establishing a temporary air monitoring site in the area, according to a recent report.

Can you monitor a smell? Will a smell turn up on a monitor or will there have to be some sort of pollute in the air?

That monitor will not measure for a group of chemicals that most concern the residents: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs. There are 16 PAHs designated as high-priority pollutants by the EPA, and several are known or probable carcinogens and can cause other health issues. Langley said the state agency plans to test for those contaminants, but the method requires samples to be sent to a laboratory for testing, preventing the agency from providing real-time results. “We are committed and will continue to respond to complaints from the area,” Langley said.

It is hard not to have some offensive smell or unneeded pollutants when storage of toxins is placed in a residential area across the river from one. This is the problem with many of the ecological problem we have in this State as well as in others.