Code Red for humanity. Not what we wanted to hear but probably what we should hear because of our inaction and ignoring climate change.

The latest climate change warning, dubbed “code red for humanity,” contains especially troubling predictions for Louisiana. Combined with sinking land, the state’s lower third – everything between New Orleans and Lake Charles – will likely see the Gulf of Mexico rise by more than 1½ feet in the next three decades, the steepest increase in the United States. Directly on the Gulf Coast, it could be worse. At Grand Isle, the water level will rise almost 2 feet by 2050 compared to today’s heights, according to a NASA estimate combining subsidence and new sea level projections. And it won’t stop there. The global sea level will continue its alarming ascent for generations to come, says the latest report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC. It declares that all evidence shows climate change to be caused by human influence and that its effects are “unmistakable” today.

nola.com

Not a pretty picture but what is the option? We are seeing this now with the extreme weather we are seeing here and around the world. The Gulf Stream is slowing down, floods in Europe and the drought we are seeing in our country,

In addition to rising sea levels, Louisiana residents already are experiencing key effects of global warming, including more intense rains, stronger hurricanes striking the coast and higher temperatures, said Virginia Burkett, chief scientist for climate and land use change with the U.S. Geological Survey, who reviewed this latest IPCC report for the U.S. State Department. Burkett, who co-chairs of the science advisory committee of Gov. John Bel Edwards’ Climate Initiatives Task Force, said the new report warns that the level of environmental change from today to the end of this century depends on whether and how quickly the world halts greenhouse gas emissions. That’s particularly important in Louisiana, a state that produces an estimated 4% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and one in which industry plays a much bigger role than it does in the rest of the country. “The carbon emission reduction discussions under way in Louisiana are illustrative of the type and scale of the actions that are being discussed globally to reach a ‘net zero’ emissions target by 2050 that would avoid warming of greater than 1.5 to 2° Celsius,” Burkett said.

Net Zero. This means for me that I use less for a company they need offsets to have other use less and they offset what the company is doing. Some question that as a viable method.

That net zero goal means any carbon or carbon-equivalent emissions must be offset by reductions, or be removed from the atmosphere and permanently stored. “The latest IPCC report only confirms what we are experiencing here in Louisiana: hotter days, higher seas and more frequent and extreme weather events,” Edwards said. “The IPCC report further underscores the need for serious climate action aimed at avoiding more extreme impacts from a hotter planet.” Federal, state and local officials are working to counter the effects of climate change, with proposals to reduce carbon emissions, forestall flooding, improve construction planning and raise the height of hurricane protection levees. Whether it’s enough remains to be seen. But clearly the state’s 20 southernmost parishes, including Calcasieu, Lafayette, Orleans, Jefferson and St. Tammany, are under siege. Other parishes also will be affected by interior flooding from both hurricanes and more intense rains.

While we are not on the coast, we still we see more Category 3 and higher hurricanes.

In the coming years, Louisianans will experience more of what the IPCC and scientists such as Burkett and Linda Mearns, a lead author on the international report, call “compound extreme events:” a Category 3, 4 or 5 hurricane accompanied by extreme rainfall and higher temperatures amid a trend of rising seas. Such a combination would mean higher storm surge along the coast and greater chances of inland flooding in more populated areas, such as occurred in Houston during Hurricane Harvey. Evacuees and storm survivors would face hotter temperatures, similar to those that were blamed for killing residents in attics in the Lower 9th Ward after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. “Southern Louisiana could very well be subjected to these three extremes that could very well happen at the same time,” Mearns said. “The Gulf Coast area in general is really not in a great position in terms of climate change.”

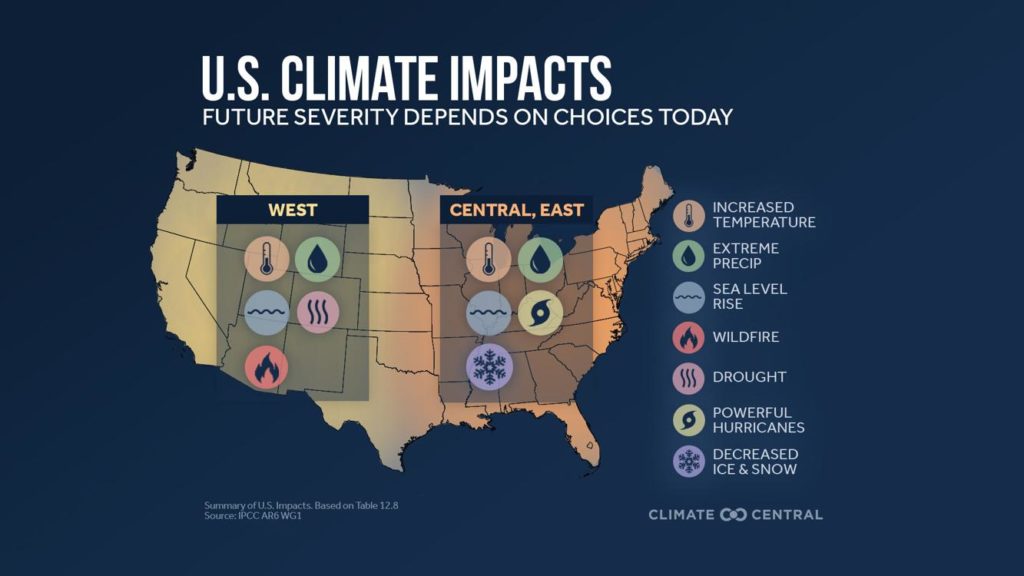

CLIMATE CENTRAL GRAPHIC

While we may not like the projections, they are well documented and researched.

Released Monday, and written by 234 scientists synthesizing information more than 14,000 research papers, the global climate assessment delivered more precise projections for a warmer world, using improved models and more on-the-ground observations of conditions attributed to climate change than were available for the panel’s previous report in 2013. Worst-case scenario: Louisiana could see the Gulf of Mexico rise more than 4½ feet if the world – and the state – continues a “business as usual” approach and make no carbon reductions. “It’s unavoidable that the sea level is going to rise for many centuries to come, and that’s going to create an escalating hazard for coastal communities,” said Robert Kopp, a lead author of the report and a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “But when we look at the second half of the century and beyond, how much sea level rise we get is increasingly sensitive to the emission choices we’re making.”

PHOTO FROM NASA

Our main problem is subsidence.

Burkett said sea level rise is more significant in Louisiana because of the underlying rates of subsidence, which is largely a consequence of the Mississippi River being leveed in the first half of the 20th century. “I’ve worked on this for 30 years, and that sinking of the delta has become less and less of an influence, compared to the main global rate of sea level rise,” Burkett said. Twenty years ago, that sinking made up 80% to 90% of the total, but now actual water rise has overtaken subsidence, she said.

CLIMATE CENTRAL GRAPHIC

Can we make the changes needed? The report doubts it. We have later too long for effective remediation.

The report casts doubt on the world’s ability to minimize global warming to an increase of 1.5° Celsius, or 2.7° degrees Fahrenheit, when compared to temperatures between 1850 and 1900. But the 2015 Paris Agreement’s primary goal of limiting the increase to well below 2° Celsius remains within reach. Kopp stressed that any reduction in greenhouse gases entering the air will help prevent the report’s gravest projections should the heated planet reach a catastrophic tipping point. “Under the most extreme future emissions, we can’t rule out that the ice sheets could shrink so rapidly we could have about 7 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century and about 16 feet by 2150,” he said. “Whereas if we can limit warming to well below 2° Celsius, we’re still going to get to 7 feet eventually, but it’s going to take many centuries, which would be a far more manageable outcome.”

CLIMATE CENTRAL GRAPHIC

For us it means that we have far more land loss.

In Louisiana, a 7-foot rise in water levels, when combined with subsidence, would likely result in the loss of another 2,250 to 4,150 square miles of coastal wetland, the amount predicted by state officials in Louisiana’s 2017 coastal Master Plan for a worst-case global warming scenario, Burkett said. Restoration projects in the 50-year plan are forecast to reduce that land loss by between 802 and 1,159 square miles. Significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions will also stave off 6 inches of global, or eustatic, sea level rise by the end of the century and limit warming, said Kopp, echoing the report’s findings. In Louisiana, it could prevent almost 1 foot of sea rise by 2100. “To stabilize the climate and to slow the rate of sea level rise, we need to get greenhouse gas emissions to net zero. And to meet the goals laid out in the Paris Agreement, we need to start getting there immediately and rapidly, reaching net zero globally before the middle of the century,” Kopp said.

Five levels of change were noted and the sad part is that the lower two still require more than we can do.

The IPCC report reviewed five future scenarios forecasting 2,000 years out with various levels of greenhouse gas emissions. The two scenarios with the lowest level of change will require strong climate policies to mitigate the effect of more greenhouse gases entering the atmosphere, Mearns said, and that won’t be easy. To date, much of the human influence on climate has resulted from burning fossil fuels and deforestation. “They, quite frankly, will require a lot of effort very, very soon. Like now,” she said. “Even waiting something like 10 years is really waiting too long.” At the state level, Edwards’ task force is reviewing more than 170 proposals for reducing, or capturing and permanently storing, carbon emissions to reach net zero by 2050. A final version of that plan is expected by early 2022.

As we have so much of our greenhouse gasses come from industry the changes have to come from the oil and gas industry.

Much of the reductions must come from either petrochemical plants or oil refineries, which were responsible for about 65% of the state’s carbon emissions in 2018, according to a recent emissions inventory by David Dismukes, executive director of LSU’s Center for Energy Studies. In that year, the state emitted about 217 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, equivalent to about 4% of the U.S. total, his study says. Louisiana state and local officials said this week they are taking steps to address the effects of climate change. Ghassan Korban, executive director of the New Orleans Sewerage & Water Board, warned that the city is among the world’s most vulnerable to climate change. The intense rains of which the IPCC report warns have already stressed the New Orleans’ 100-year-old pipe-and-canal drainage system. “While we are proud to operate one of the largest stormwater pumping systems in the world, this system isn’t enough to mitigate flooding from the increasingly intense and more frequent storms we’re seeing today and are likely to continue to see in the future,” Korban said. “Adapting our city to capture stormwater where it falls, to relieve the pressure on our drainage system, is the only way we can maintain our quality of life in the face of these massive challenges.”

The city also is concerned and taking some steps.

Ramsey Green, chief resilience officer and deputy chief administrative officer for Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s administration, agreed. “It’s jarring. It’s unmistakable what’s happening. It almost feels like nowhere is safe,” Green said. “It reminds me a little bit of during the BP oil spill, me screaming at my television, saying ‘Cap it! Cap it! Cap it!’“ “The people who can cap [global warming] are all of us as a global society,” he said. New Orleans has dedicated $300 million to projects to hold rainfall, instead of simply directing runoff into the pipes and canals, he said. “It takes billions of dollars to upgrade pipes, to upgrade pumps,” Green said, “but it takes millions of dollars – low millions of dollars – to turn parks into bioswales and sponges to keep water from the low-lying parts of our city.” One such project will find ways to hold as much as 52 million gallons of stormwater in different parts of City Park, to offer some relief for the drainage system, he said.

As residents there are things we can do as well.

Individual residents can help by making similar, smaller efforts in their own front and back yards. “I’m sort of practicing what I preach,” Green said. “I’m finishing a project at my own home right now, holding at least a couple thousand gallons on my own property because it makes it beautiful, and it’s better for the city.” The Louisiana Watershed Initiative, created in part to address the number of more intense rains across the state, is investing in technological improvements that will eventually help planners adapt to flood risk, said Pat Forbes, executive director of the state Office of Community Development. One project is developing a combined water flow model for the coastal zone, to tie together the results of existing river flow models and the models being used by the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to predict storm surge effects.

To gain historical data the city is working with the federal government.

The state also is working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to update that agency’s atlas of intense rainfall events. “The data in the current atlas are over 10 years old,” he said. “We are providing them with additional rain gauge data.” The result will eventually be used by state Department of Transportation and Development contractors who are developing new river flooding models to help predict when and where future intense rain flooding will occur. Such data will be useful if the state takes Burkett’s advice to apply the IPCC’s new findings to all of the state’s infrastructure. “And not just the levees on the coast, but also the size of culverts and the base elevation of highways and bridges access the state,” she said.

The Corps of Engineers is also a player in this mix. We see them with the levee work that is going on.

Keeping the state’s existing and future levee systems elevated in the face of subsidence and rising seas will likely be a task for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A hint of its strategy is contained in its recent reports on the proposed $1.7 billion, 50-year east bank and West Bank hurricane levee elevation plan. “As long as the levee lifts are frequent and include some overbuild and are based on the latest available surge hazard data, the project should be able to maintain” its ability to withstand topping by a flooding event, including hurricane storm surges, that have a 1% chance of occurring in any year, the east bank report said. Keeping up with the increased sea level rise will require maintenance and money, said Corps spokesman Ricky Boyett. “Nevertheless, with long-term maintenance and the necessary funding, we can adapt designs and elevations to account for any change in actual or projected relative sea level rise rates,” he said. Chris Humphreys, engineering director for the east bank levee authority, said the Corps levee lift project reports do include good news: Concrete structures such as the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier and the West Closure Complex were built to anticipate 30 years of sea level rise and subsidence, so there will be at least some time to adapt to more rapid sea rises. Green also pointed to provisions in the $1.2 billion infrastructure bill that the U.S. Senate approved Tuesday. They could be used by private industry to come up with innovative methods of reducing carbon or adapting to climate change. “If we can shoot Jeff Bezos to ‘barely space’ for 10 minutes that costs billions of dollars, what can we do that costs billions of dollars to create a for-profit mechanism for reducing the impacts our lifestyle have?” he said.

So there are option and they include all players from federal agencies to us, the residents. Something needs to be done but do we have the will to do so? In our divided government half say there is no need the other have says there sure is.