After every event, there is what the military calls a “hot wash”. The response is looked at that evaluated and the though of want to do in future events are discussed. We are starting tosee that with Ida.

Two years ago, Mayor LaToya Cantrell said New Orleans would need to move more nimbly to evacuate before the next major hurricane, after Hurricane Michael blew onto the Florida Panhandle more quickly and more intensely than expected. Michael, a Category 5 monster, left 16 people dead and $25 billion in damage. But in the wake of Hurricane Ida – which also intensified faster than projected – storm experts question how much New Orleans and neighboring parishes can do to outrun a Mother Nature that may be getting fiercer. “If it’s taking us longer to prepare to evacuate than the storms are giving us, what can we do differently? That’s a key question now,” said Craig Fugate, who oversaw FEMA under President Barack Obama. Fugate and other experts are asking the question because officials at the National Hurricane Center are projecting more intense storms in the future, with many people blaming global warming.

nola.com

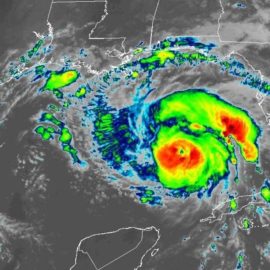

Ida was named and then shortly became a Cat 4. That is too fast for normal reporting requirements.

Ida hit the coast of Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane on Sunday, just three days after becoming a named storm. It developed and moved so quickly that National Hurricane Center officials issued dire warnings later than they would prefer. The biggest question Cantrell then faced was whether to order a mandatory evacuation and ask state officials to implement a contraflow plan, where inbound lanes on highways and interstates are reversed to get people out faster. She decided not to do so. That appears to have been a wise decision, said Brian Wolshon, an LSU civil engineering professor who has helped devise dozens of evacuation plans, including those in Louisiana. “If we look at the fundamental reason why evacuations are used, it’s to save lives,” Wolshon said. “It’s not to make lives comfortable. It is, pure and simple, a life-and-death issue. Did anybody die because they couldn’t evacuate? If the answer is no, you can make the case that it was the right decision.” He added, however, “for some people not having electricity following the storm or access to clean water and food can be a life-and-death condition. Thus, when people are evaluating their decision they must also assess their personal level of threat and they need to consider that in their planning and preparation.”

Even now, a week later, all the reporting is not in. It will be complicated as was the death due to the storm or the power loss?

Gov. John Bel Edwards has said it’s too early to know how many lives Ida cost, but the number appears to be small, compared to past disasters. Just three have been recorded thus far in Louisiana. Ida swamped the New York City region Wednesday night, causing at least eight deaths. The loss of power in New Orleans, however, has left tens of thousands of people in sweltering homes with no fresh fruit, meat or vegetables in their refrigerator. Many of them now want out of the city. Health complications from the heat are a peril, especially for the frail. Wolshon said New Orleans’ existing evacuation plan “is pretty damn good, although it’s not perfect.” He noted that federal, state and local officials carry out simulations together to test their evacuation plans.

Evacuations we can do but this one had multiple evacuates, one for the hurricane and the other as the power loos continued.

New Orleans and surrounding parishes have extremely detailed and complicated plans to move residents out of harm’s way in advance of a major hurricane. “You make assumptions about how many people will leave and how quickly they’ll get on the road and how long the evacuation will take. The evacuation decisions work backward from there. That’s the framework,” said Jay Baker, a retired Florida State professor of geography who has helped devise evacuation plans for years. “The problem is there’s uncertainty – where the storm is going to hit and how bad it will be when it hits.” For a time, Ida appeared headed toward Baton Rouge. But then it jogged east, leaving damaged and waterlogged houses and businesses across a swath of parishes, hitting Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Charles and St. John parishes especially hard. “The unknowns become known only after the fact,” Wolshon said. He and the others emphasize that hurricane evacuations require considerable time to implement.

Evacuations progress from the closest to the storm to the farthest.

The evacuations begin with the coastal parishes, to give residents time there to get out. Metro New Orleans residents are supposed to leave later to avoid clogging the major roadways. New Orleans has an added complication because the city is home to tens of thousands of poor residents without cars. So state mandatory evacuation plans call for RTA buses to pick up evacuees throughout the city and take them to the Smoothie King Center, where they would board 750 private tour buses that would ferry them out of the city. But the city needs at least 72 hours of advance notice to order the buses and organize the other parts of its evacuation plan. “With the window we had, we didn’t have enough time,” said Mike Steele, communications director for the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, which was created after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita devastated south Louisiana in 2005. The National Hurricane Center issued its hurricane watch just 54 hours before Ida made landfall, and its more serious hurricane warning only 30 hours beforehand. “This was a rapidly intensifying storm,” Fugate said.

We like a slow moving storm with a definite path and dies not deviate from the projections. That is not nature, especially in these days of climate change.

New Orleans’ system is designed for a slow-moving storm, such as Hurricane Gustav in 2008. That storm marked the last time New Orleans implemented the contraflow system, Steele said. Gustav, which had appeared headed for the city, wound up making landfall near Cocodrie in Terrebonne Parish. Steele pointed out that contraflow requires the coordination and cooperation of numerous parish governments and neighboring states. Because contraflow involves blocking exits along the way, to force people to travel long distances as they flee, it also requires law enforcement along the route, the repositioning of barricades and the placement of fuel trucks for cars that need gas. “It’s basically a Hail Mary to get people away from the coast if they haven’t left already,” Steele said. He added that state officials will begin meeting in several months to study what went right and wrong with advance plans for Ida. “We absolutely learn lessons from every event,” Steele said. “We never get everything 100% right.”

So true! And it looks like unpredictability will be the watch word for the future.

If hurricanes become more unpredictable, Baker said disaster planners could start requiring evacuations earlier to avoid being surprised. “But then you could have the ‘cry wolf syndrome,’” he said, where a miss one time might make people reluctant to heed warnings to leave next time. Something like that happened in 2004’s Hurricane Ivan, which left thousands of New Orleanians stuck in interminable traffic for a storm that wound up well to the east. Some analysts said that contributed to some people not evacuating in advance of Hurricane Katrina, which drowned New Orleans and left more than 1,800 people dead. Nonetheless, Baker believes that people in most cases still will evacuate the next time if they think the coming hurricane poses grave peril. “The main reason people don’t evacuate is because they don’t think they need to,” he said. Fugate said if hurricanes are indeed becoming more intense, officials may need to modify plans that call for people to get completely out of the hurricane zone. Officials, he said, may need just to send people to areas where they will be safe from harm.

That means we are the deciding point. The city recommends and we react. My wife says never again so we are more likely to evacuate the next time. We are probably not the only ones as this was a double whammy as the power loss was worse than the storm.