Hurricane Ida did far more than hit us. Wetlands were hit badly and their recovery is slow. No insurance claim from them!

Hurricane Ida might be responsible for the loss of 106 square miles of wetlands, an area only slighter larger than Baton Rouge, with most of the loss occurring in the Barataria Basin south of New Orleans, the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority was told Wednesday. “It’s incredibly significant,” Brady Couvillion, a geographer with the U.S. Geological Survey, said of the preliminary estimate. “This is probably the most impactful storm we’ve seen since Hurricane Katrina, and it’s definitely the most impactful event for the Barataria Basin in recorded history.” But Couvillion cautioned the final loss total is likely to shrink, as wetlands reestablish themselves over the next year or so. “We saw this with Katrina,” he said of the 2005 storm, which was blamed for turning more than 200 square miles of wetlands into open water along Louisiana’s coast. “We saw this with Rita, Gustav, Ike. These initial numbers are often inflated, as they have some ephemeral effects in them, and as we continue to observe things, these numbers will go down.”

nola.com

THis appears to be a usual occurrence but not one that we can afford.

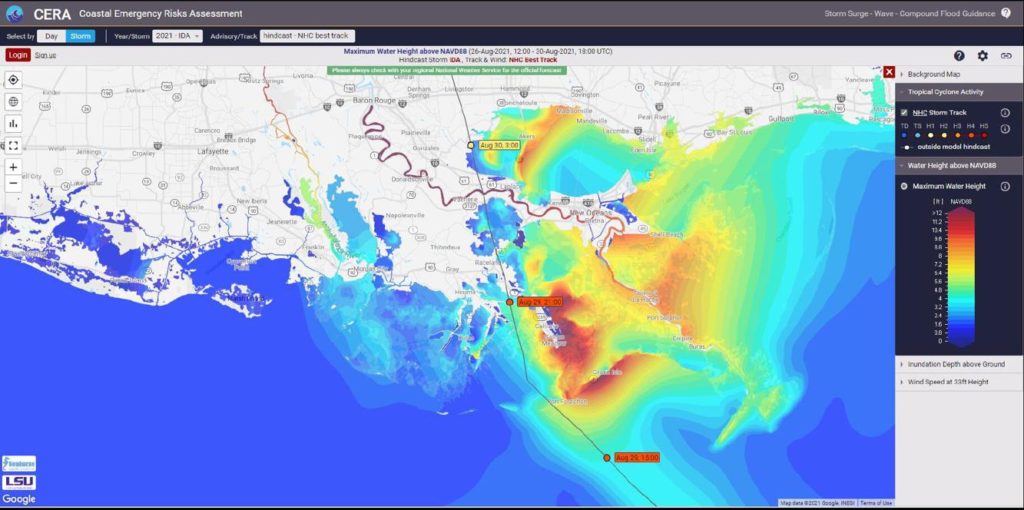

Still, Wednesday’s estimate, the first to put a number on the size of wetlands lost to Ida, underscores the increasing vulnerability of southeast Louisiana at a time when climate change is causing more intense storms. The estimates include the loss of flotant, a type of wetland grasses that grows in a mat on the water’s surface and is connected to water bottoms by long roots. But they don’t include aquatic plants that simply grow on the surface of the water. Couvillion said another part of the estimate totals that is likely to change are areas where some flotant, other vegetation or mud redirected by Ida shows up as new land. Plant life that is moved into areas of open water, often called wrack, is likely to disappear as it decomposes. He said scientists must wait weeks, months or longer to assure that high water levels caused by the storm or other issues aren’t obscuring how much land and wetlands were actually lost. As an example, he showed a satellite photo of an area of wetlands and flotant just south of Lake Salvador. It looked as if it had turned to open water on Aug. 30, the day after Category 4 Ida made landfall at Port Fourchon, packing sustained winds of 140 mph and pushing a storm surge in excess of 12 feet into portions of the Barataria Basin. “There were some early reports showing this image of complete doom and gloom for all of the Barataria Basin,” he said. “But that’s an important aspect of how we study wetlands. We can’t look at one particular day. We knew that a lot of this was just ephemeral flooding. “Instead we gave it some time and we collected more imagery, and unfortunately when we started looking at imagery that was removed from the event, we did find a lot of persistent wetland loss, Couvillon said. He used before and after photos of that same area, with the later photo from Sept. 24, almost a month after the storm, as an example.

This map shows the estimated height of storm surge caused by Hurricane Ida.

LSU COASTAL EMERGENCY RISKS ASSESSMENT ILLUSTRATION

By then the amount of open water was coming into view and not a picture that was appealing.

By then, it was clear that large areas south of Lake Salvador, east of Delta Farms and Clovelly Farms and west of Little Lake, had turned into open water. The chair of the coastal authority, Chip Kline, said the location of those lost wetlands are significant, as they served as a buffer for the Larose to Golden Meadow hurricane levee. Couvillion said he expects a more accurate estimate of the Ida losses in the results of his agency’s update of Louisiana’s coastal land loss, which will be published in early 2022. But even then, future adjustments are likely as more wetlands regain their footing, following next spring’s natural growout. He said the updated report was supposed to have been released this fall but was delayed to capture Ida’s effects. The report also will address similar land loss that occurred in the aftermath of hurricanes Laura and Delta in 2020 in western Louisiana, he said.

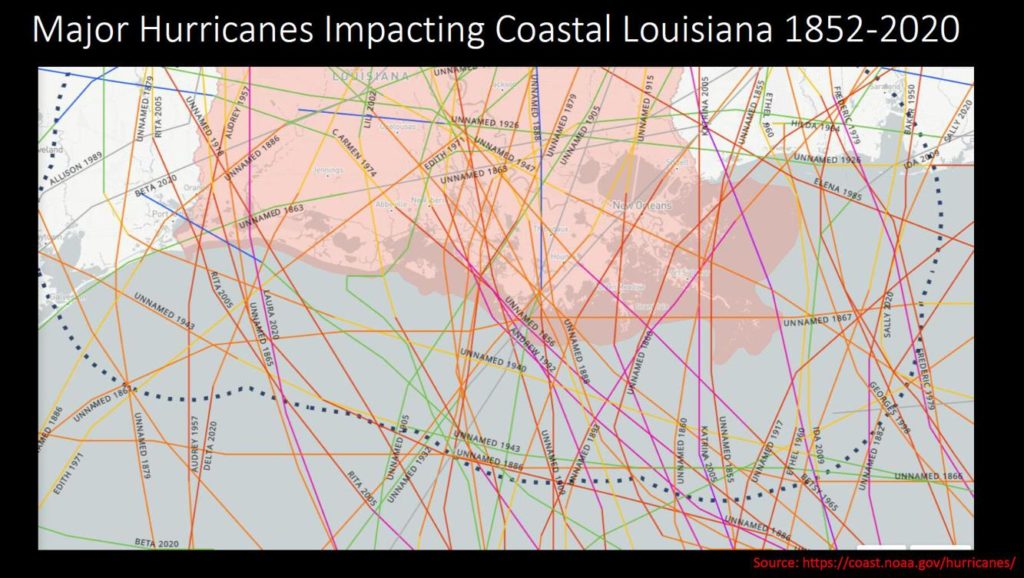

NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION ILLUSTRATION

.Linking hurricanes to land loss is a new idea and not one that the past showed.

Couvillion said there is little past research linking major hurricanes and land loss. Most past studies focused on other known issues, such as subsidence, loss of sediment caused by the Mississippi River levee system and the construction of canals and navigation channels for oil and gas and commerce. The coast has lost more than 1,900 square miles of land and wetlands since 1930, he said. But more recent studies, like the Geological Survey’s review of wetland losses associated with Katrina in 2005, have indicated storms are a significant player. As a result, he said, Ida’s damage comes as no surprise.

The only thing that is certain is that we will have more and stronger hurricanes causing more damage.