Hurricane Katrina was the beginning. Multiple breaches of the flood protection system flooded the city. I am sure someone said “never again” and that is where we are now.

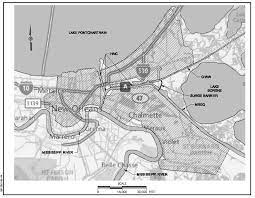

After Hurricane Katrina and the 54 breaches that inundated the New Orleans area, the federal government set out to remake southeast Louisiana’s flood protection. Work was finally completed on the $12 billion network of levees, gates and floodwalls this year, and the Army Corps of Engineers handed over the entire system to the state, with local levee authorities now overseeing their upkeep. Work on related drainage projects amounting to $2.5 billion is ongoing. It’s an engineering marvel that includes the world’s largest pumping station and a “Great Wall of Louisiana” to protect New Orleans from storm surge. It is essentially a fortress with a 133-mile perimeter around the metro area, not including 70 miles of internal risk reduction structures. It provides protection for five parishes: Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard, Plaquemines and St. Charles.

nola.com

While it is vastly improved, it is not impregnable. We can still get wet.

But while its designers say it is a vastly improved system compared to what existed during Katrina, they also readily admit that it by no means provides total protection from storms. Here’s what you need to know on the vast flood protection network with the alphabet soup name: HSDRRS, or Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System.

Will it protect us from all hurricanes?

Absolutely not. The system is high enough to protect against surge from 100-year storms, or those with a 1% chance of occurring in any year. A better way of understanding such an event’s risk is that it has a 26% chance of occurring in the lifetime of a 30-year mortgage. In a time of rising seas and intensifying hurricanes linked to climate change, it will almost surely be overtopped one day. Residents should still have an evacuation plan for when it is needed. That said, according to the Corps, the levees and floodwalls are designed in a manner intended to prevent their catastrophic failure even when they are overtopped, through the use of armoring and other features. So while water may enter parts of the city from levee overtopping and cause damage, it can in theory be pumped out if internal drainage features are operable. The major breaches, flooding of pump stations and loss of power during Katrina made that impossible, eventually flooding 80% of the city and resulting in one of the worst tragedies in American history.

The Great Wall of Louisiana? What is it composed of?

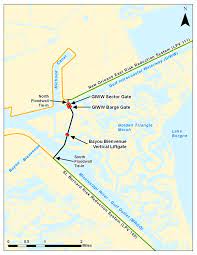

A key issue in designing the new system was protecting against devastating storm surge being pushed toward the city from the Gulf. A major part of the solution is the Lake Borgne Surge Barrier. It is what its nickname suggests: a giant wall cutting across the triangle where two shipping channels, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet, meet east of the city. The now-closed MRGO (or “Mr. Go,” as it’s known to locals) was blamed for helping funnel storm surge into the city during Katrina. The wall stretches 1.8 miles and stands up to 26 feet above sea level. It includes a floating barge gate and a sector gate at the Intracoastal, both 150-feet-wide, as well as a 56-foot-wide vertical lift gate at Bayou Bienvenue. However, the huge wall is lower than the floodwalls it connects to in St. Bernard and New Orleans, which are 30 to 32 feet above sea level. The barrier is designed to allow some surge water to overtop it and be stored in the Central Wetlands Unit along parts of Chalmette, Arabi and the Lower 9th Ward, where a lower interior levee keeps it from moving into populated areas.

Are there other key elements in the system?

The list is long, but here are some highlights: The West Closure Complex is located near the confluence of the Harvey and Algiers canals on the Intracoastal Waterway. The pumping station at the complex is the biggest in the world, able to pump enough water into upper Barataria Bay to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in only 4 seconds. It also includes a floodgate, floodwalls and other flood control structures, Seabrook Floodgate Complex helps protect New Orleans from storm surge arriving through Lake Pontchartrain, Combined pump stations and floodgates at the ends of the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue and London Avenue drainage canals in New Orleans allow rain and floodwater to be pumped into Lake Pontchartrain, while blocking surge, A network of connected armored levees and floodwalls on both the east and west banks and The entire project is designed to work together as a system.

This sounds good but has it been tested or is the first hurricane the test?

Sort of. Hurricane Ida roared ashore last summer as a Category 4 storm and one of the most powerful to ever make landfall in Louisiana. The system held up well, officials say. But it also turned out that Ida wasn’t the sternest of tests. A slight shift in path could have posed a far greater threat. Parts of the east bank system survived a greater surge test during Hurricane Gustav in 2008, well before the system was completed.

What is left to do as we enter another hurricane season?

Congress is considering proposals to study boosting the system to 200-year-storm level. One important aspect of upkeep in the years ahead will be lifting the levees when they fall below 100-year-storm level due to subsidence and sea level rise. The Corps has proposed a $3 billion, 50-year plan to do that. The state has been seeking funding to extend protection beyond where it exists now. That would include the Upper Barataria flood protection project for portions of seven parishes: Ascension, Assumption, Jefferson, Lafourche, St. Charles, St. James and St. John the Baptist. The West Shore Lake Pontchartrain levee, including parts of St. Charles and St. John, is under construction. The 92-mile-long Morganza-to-the-Gulf project, designed to protect Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes, remains under construction.

It is built and has been tested, but not as a complete system. So the first major storm will be the first real test.