This is a picture of a salt water marsh. They are expanding in our state and reducing the fresh water marshes.

It’s no secret that Louisiana’s crucially important saltwater and freshwater wetlands have long been fading away. But a new study shows things could get far worse. It’s no secret that Louisiana’s crucially important saltwater and freshwater wetlands have long been fading away. But a new study shows things could get far worse. The study focuses especially on the problem freshwater wetlands have in moving inland: They can’t take over areas that have been turned into levees or have been developed into elevated population centers, the study found. “Louisiana is the state with the highest potential for wetlands loss, the highest potential for wetland migration, and the highest potential for ecological loss and transformation due to migrating wetlands,” said Michael Osland, a research ecologist at the USGS Wetlands and Aquatic Research Center in Lafayette and lead author of the study published last week in the journal Science Advances.

nola.com

It is no consolation to know that we are not alone. Other coastal states are having the problem we just have it worse.

And Louisiana is not alone. All of the saltwater wetlands along the nation’s shorelines, like those that support commercial fisheries along the Louisiana Gulf Coast, are expected to migrate well inland by 2100 because of sea level rise. But the new study finds that two-thirds of that saltwater wetland migration will come at the expense of equally valuable freshwater wetlands, especially in Louisiana, Florida and North Carolina. The remaining third are likely to be at the expense of upland areas now used to grow crops, forests, pastures and grasslands, according to the study led by scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey. The more than 4,000 square miles of saltwater-dominated wetlands in Louisiana that are expected to migrate inland by 2100 are vital to the survival of coast-living wildlife and fisheries, but are also important in protecting coastal communities from storm surge, improving water quality, and providing recreational opportunities for the public, Osland said. “However, they’re also highly vulnerable to sea level rise, especially at the elevated rates that are expected under higher greenhouse gas emissions,” he said. To put that in perspective, the land area of New Orleans is only about 170 square miles, but its borders also include 181 square miles of water, including some of that at-risk freshwater wetlands.

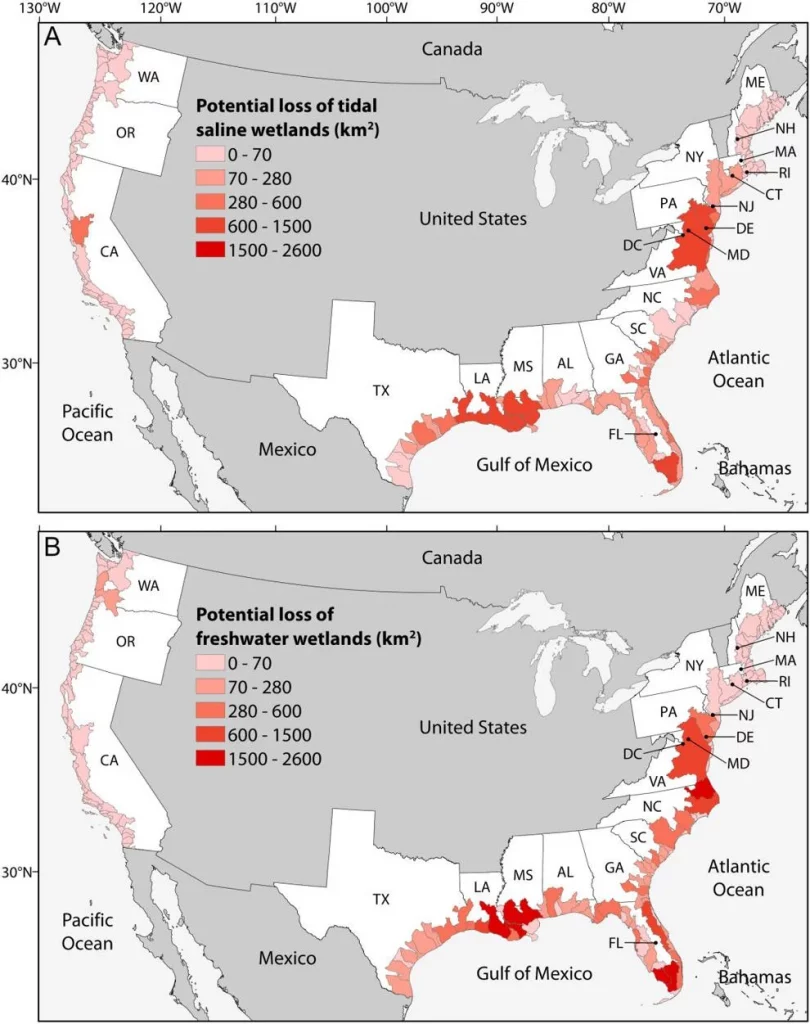

This map shows the areas where the greatest areas of saltwater and freshwater wetlands are expected to migrate inland by 2100 because of sea level rise. Researchers estimate as much as 4,025 square miles of saltwater wetlands will move inland in Louisiana, replacing large areas of freshwater wetlands and some upland crops and forests. Only about 150 square miles of freshwater wetlands will move inland.

(Science Advances) Science Advances

The study used the higher end of the projected sea rise.

The study used an intermediate to high estimate of sea level rise developed in 2018 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, equivalent to a 4.9-foot average rise worldwide by 2100, to estimate wetlands migrations in 166 estuaries along the U.S. coastline. Coastal saltwater wetlands do have the potential to adapt to rising sea levels by growing at rates fast enough to outpace the rising water. In Louisiana, however, more than in other U.S. coastal locations, natural sinking of the land on which wetlands are growing and erosion caused by human activities, hurricanes and other weather events add to the threat of wetlands turning to open water. The study estimated the combination of climate-caused sea level rise and subsidence will result in an average 8.5-foot rise in water heights in Louisiana by 2100. But Louisiana’s coastal zone also includes hundreds of square miles of freshwater wetlands that will themselves be killed by salt water moving inland because of sea level rise, with some of that loss replaced by the inland expansion of saltwater-tolerant wetland grasses.

(Photo by Michael Osland, U.S. Geological Survey) Michael Osland, U.S. Geological Survey

This is a wake up call, but we have as history of ignoring them.

“It means there’s going to be a net loss of coastal wetlands,” said John Day Jr., an emeritus professor of coastal sciences who has studied Louisiana’s wetlands for more than 50 years and is a co-author of the study. “We knew that. But it means the landward migration is not going to replace our existing coastal marshes.” And Day said the study is a wake-up call that the impacts of climate change need to be considered as part of the state’s strategy for both restoring and protecting wetlands as well as those who live in the coastal zone, which amounts to more than half of Louisiana’s population. “We have clearly entered the new era of climate change,” he said, and wetlands migration driven by sea level rise is just one factor. Coastal Louisiana is also impacted by increased Mississippi and Atchafalaya river discharges driven by more rain and intensifying hurricanes, both linked to global warming. “If Hurricane Harvey had parked itself over New Orleans, the city would have filled with water,” he said, referring to the 60 inches of rain over five days that the hurricane dumped on the Houston area in 2017.

We have known of the growth for years but not about the loss of fresh water marshes.

Past reviews of wetland migration along the nation’s shorelines have resulted in mostly positive conclusions about their ability to expand inland. The new report, however, makes clear that most of that expansion comes at the expense of freshwater wetlands. That’s because as freshwater plants attempt to also move inland away from saltier water, they run into brick walls, often literally with Louisiana’s extensive hurricane levee system, but also because of other human development. “Two-thirds of that potential inland migration across the country is at the expense of these valuable freshwater wetlands,” Osland said.

We have the potential for the growth of the salt marshes.

The researchers found that in Louisiana, there is the potential for 2,766 square miles of saltwater wetlands to move into freshwater wetland areas. Another 1,259 square miles of saltwater wetlands could migrate into upland areas, possibly including rice paddies, crawfish ponds and sugar cane fields, and forested swamps. But the researchers concluded there was only room for upland expansion of about 150 square miles of freshwater wetlands into uplands. Florida’s wetland migration limitations are not much better, the researchers found. They expect 2,865 square miles of mostly saltwater mangrove forests to move inland into freshwater wetlands, including in the Everglades, with another 571 square miles of saline wetlands relocating into what are today uplands. Only 167 square miles of Florida’s existing freshwater wetlands will be able to relocate into uplands. Similar migration issues will be seen in Texas, Mississippi and Alabama on the Gulf Coast, while Mid-Atlantic states like North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Maryland seem to have greater areas for freshwater wetland retreat.

(Science Advances) Science Advances

We need to keep the temperature rise to a minimum but our current track is not to meet the minimum but exceed it.

The study also raises serious concerns about the consequences of not keeping worldwide temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, which could result in global water heights of as much as 8.2 feet. In Louisiana, with subsidence, the water heights could be as much as 10 feet above present levels. That worst-case sea level rise scenario would result in saltwater intrusion causing the collapse of thousands of miles of existing saltwater and freshwater wetlands, again exacerbated by human-caused barriers to their migration inland. “The risk of catastrophic, landscape-scale wetland loss is especially high along the Gulf of Mexico and south Atlantic coasts, with hot spots in the Mississippi River Delta, Everglades, Albemarle-Pamlico, and Chesapeake Bay estuaries. The five states with the highest potential for wetland loss are Louisiana (29%), Florida (25%), North Carolina (10%), Texas (8%), and South Carolina (7%), which collectively account for 79% of the total potential wetland loss,” the study said.

Between one political party and the Supreme Court we are blindly heading to oblivion and will be seeing more heat, more rain and more storms. And less water in the west. When will we wake up? When it is too late?