There is a proposed offshore wind farm to be off Lake Charles. Public comment is out and Louisiana is silent.

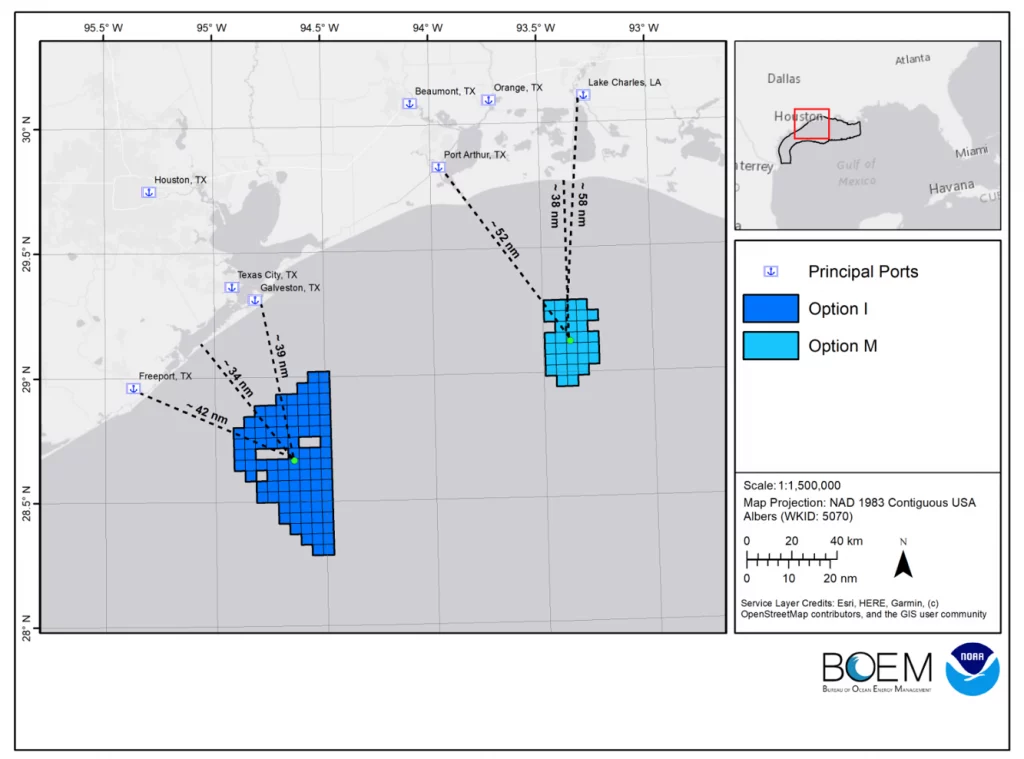

Federal regulators have heard little from Louisiana about a wind energy zone proposed in the Gulf of Mexico near Lake Charles, part of a push by President Joe Biden’s administration to generate 30 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2030. The U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has been asking the public to weigh in on the Gulf’s first two proposed wind energy zones: the 188,000-acre area south of Lake Charles and a 547,000-acre area near Galveston, Texas. The Lake Charles zone, which would be located about 38 miles from the coast, could generate power for almost 800,000 homes – about half the households in Louisiana – and spur engineering and construction jobs for a region hit hard by Hurricane Laura and other storms. The Galveston zone could produce enough power for 2.3 million homes, according to BOEM estimates.

nola.com

BOEM

The comment period has been extended to 02 September as only 60 comments have been submitted, most from Texas.

BOEM recently extended the comment period from late August to Sept. 2. As of Monday, BOEM had received 60 comments on the proposed zones. Most of the comments were from Texas groups and residents. The most common concerns were over the survival of migratory birds and ensuring that wind farms offer safe, good-paying jobs. The Houston Audubon Society urged BOEM to balance clean energy goals with the safety of the millions of birds that migrate across the Gulf each year. “We recognize the need to deliver renewable energy options as soon as possible, but doing so without sufficient data and analysis could result in a poorly designed project with unintentional but significant impacts to bird populations, the ecological services they provide, and the nature-based economy that they support in Texas,” the group wrote, estimating that about 4 million people participate in bird-watching in Texas each year. The state of Texas weighed in, urging BOEM to consider the health of birds and bats, as well as the creatures living on the seafloor, which could be affected by wind turbine transmission lines. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department stressed that the Gulf ecosystem is different than the waters off New England, where most offshore wind research and development in the U.S. has occurred. Several Texas residents asked BOEM to make sure offshore wind jobs benefit a wide cross-section of the state’s population. “What I care about most is jobs that create economic opportunities for historically-disadvantaged residents in my community,” a Houston resident wrote.

Where is Louisiana? Both economic and environmental concerns will be considered.

BOEM Director Amanda Lefton promised to closely consider economic and environmental concerns. She noted that the two zones are smaller than initially proposed to avoid potential impacts on commercial fishing, shipping, military activities and protected marine species. “We are committed to a transparent, inclusive and data-driven process that ensures all ocean users flourish in the Gulf,” Lefton said last month.

Louisiana seems to be focused on money.

Louisiana leaders have offered little input on the the proposed zones, appearing more focused on the money wind farms might generate than their potential impacts. The state’s congressional delegation is promoting bills that ensure that Louisiana gets a large cut of the money the federal government will collect from wind energy companies. While BOEM charges fees for offshore wind lease areas, there are currently no revenue-sharing provisions. A bill co-authored by Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., would change that. The Reinvesting In Shoreline Economies and Ecosystems Act aims to boost Louisiana’s share of offshore oil and gas revenue and channel a nearly 38% share of federal offshore wind fees and royalties to states with wind farms near their coasts. Last month, U.S. Reps. Steve Scalise, R-Jefferson, and Troy Carter, D-New Orleans, introduced similar legislation that would increase the share of wind and fossil fuel revenue to states to 50%. BOEM charges the offshore wind industry for lease areas but does not take a share of royalties, as it does for the oil and gas industry. That’s because offshore wind is still in the development phase in the U.S., with construction costs high and profits relatively low.

Courtesy of Gulf Island

Louisiana just passed a law that may deter offshore wind farms.

Louisiana recently passed a law requiring royalties from wind farms in state waters, a move that some industry groups say could steer wind developers away from Louisiana. Gov. John Bel Edwards has promoted offshore wind as a key strategy for reaching his “net zero” carbon emissions goal by 2050. His Climate Initiatives Task Force hopes to have enough offshore wind infrastructure in place to generate at least 5,000 megawatts by 2035. Louisiana business groups expect a flurry of economic activity once construction begins. Several companies rooted in the offshore oil and gas industry have already transitioned to servicing offshore wind farms. In January, the Clean Power Association predicted two wind farms in the Gulf would likely create as many as 17,500 jobs. BOEM will accept public comment on the two wind energy zones until Sept. 2. For information, visit boem.gov/renewable-energy/state-activities/gulf-mexico-activities.

Louisiana needs to get on the ball and support this and not just worry about money.