(Tropical Tidbits)

This was to be another bad year for hurricanes but the forecast so far is not living up to it.

Sometimes forecasts don’t pan out. Other times they do — but what was predicted is delayed. Regardless of which is true this year, Atlantic tropical storm and hurricane activity, thus far, has been strangely quiet — especially given forecasts for a busy season. Observed activity is barely 15 percent of what’s normal up to this point. With little activity of immediate concern on the weather maps (the National Hurricane Center is tracking two disturbances with small chances to develop), it’s tough not to wonder what’s up. So far, atmospheric ingredients simply haven’t gelled. But they still could, as we’re just now entering the peak of the season, which spans late August through early October. And, as Hurricane Andrew demonstrated 30 years ago, it takes only one storm for a quiet season to become a catastrophe. This year’s silent spell comes five years to the day since the landfall of Category 4 Hurricane Harvey near Rockport, Tex., in 2017. The system then transitioned into a stagnant tropical rainstorm that delivered catastrophic flooding around Houston. Harvey was a prelude to a devastating September that brought Irma, Maria and a slew of other storms.

washingtonpost.com

This is unusual bit how rare is it?

A named storm hasn’t roamed the Atlantic since Colin dissipated on July 3, and even that storm was a marginal one. Since that storm grazed the Carolinas’ coasts, the Atlantic Ocean has been dormant. The dearth of named storms is rare, but it’s not unprecedented. According to Philip Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University, this marks the first time since 1982 that there hasn’t been a single named storm anywhere in the Atlantic between July 3 and the penultimate week of August. It’s happened five other times since 1950, making a quiet stretch this long leading up to peak season a roughly once-a-decade event. During that 1982 season, only six storms formed, and the United States never experienced a hurricane landfall. The season tied with 2013 for having the record fewest named storms in the satellite era. There’s a growing chance that August could draw to a close without any named storms. That hasn’t happened since 1997. Before that, you would have to go back to 1961 for a storm-free August. It also happened in 1941 and 1929.

What happened in those years?

The 1929 season did later feature a Category 3 that made landfall in the Florida Keys in late September with a 150-mph wind gust in Key Largo. In 1941, the first system didn’t form until Sept. 11, and only six wound up roaming the basin. A few did make landfall, including the Texas Hurricane of 1941, which swung ashore just east of Houston as a Category 3 with 125 mph on Sept. 23. A Category 2 also struck Florida in early October. The 1961 season awoke suddenly in September, with three Category 4 storms and a pair of Category 5s forming through the end of October. Among them was Carla, which was a large and intense Category 3 when it made landfall near Port O’Connor, Tex., on Sept. 11. In addition to wind and rain, it unleashed a slew of tornadoes, including a devastating F4 that killed eight people in Galveston.

What is happening to make it so quiet?

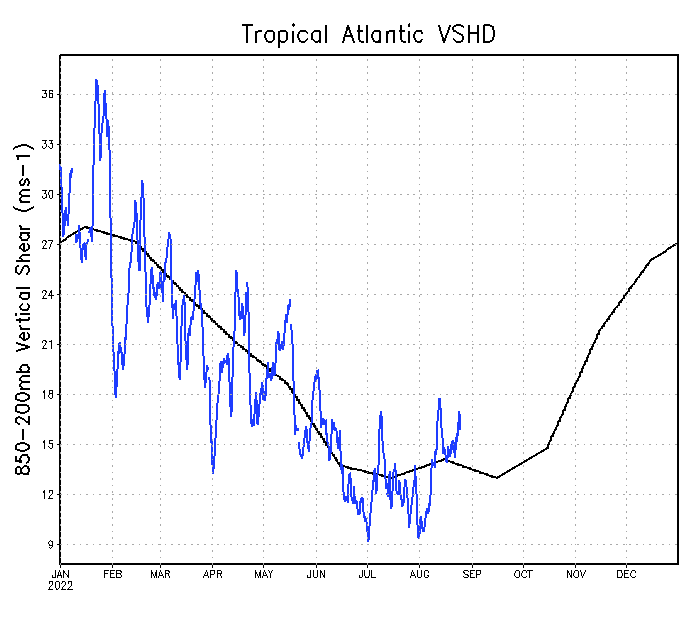

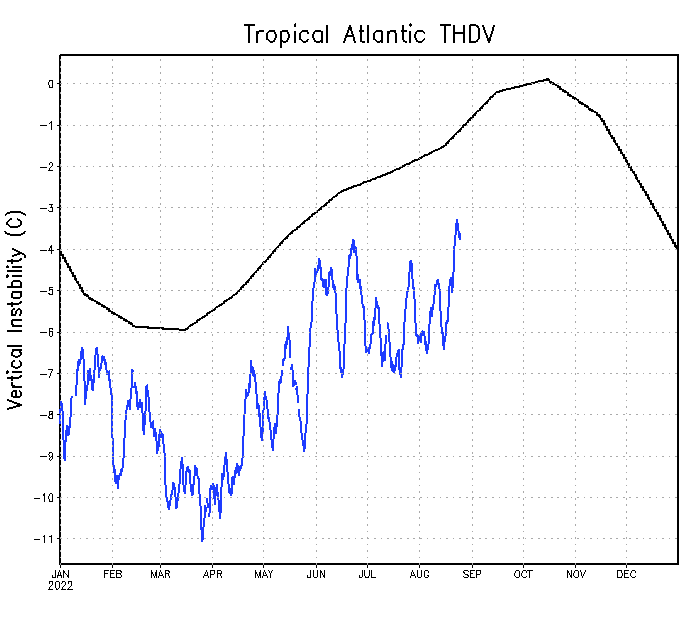

Atmospheric scientists have hunches, but it’s not obvious why the Atlantic is in a lengthy slumber. Ironically, the eastern Pacific Ocean, which was expected to be quieter than the Atlantic, has been active. It has already burned through the first 10 names on the Hurricane Center’s naming list. Seven of the storms have reached hurricane status. Usually when one basin is busy, the other is quiet. But Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, writes that the Pacific probably isn’t to blame. “If there was a tremendous amount of intense hurricane action going on in the eastern Pacific, there could be,” he explained, as that might result in sinking air that could quell hurricane activity in the Atlantic. “But that’s not the case.” He noted that the Pacific is only 13 percent ahead of where it should be in terms of ACE, or Accumulated Cyclone Energy — a measure of how much energy from warm waters tropical storms and hurricanes convert into expend on winds. The western Pacific, he explained, is 71 percent below average. “Averaging across those three major tropical cyclone basins in the northern hemisphere, 2022′s ACE is roughly 55 percent of the average value,” he wrote in an email. So what’s the deal? There are two main factors that are needed to brew a hurricane: light high-altitude winds, and instability; or the warm, humid air needed to fuel a storm. While the winds haven’t been particularly favorable for storm formation, they also haven’t been abnormally hostile. In fact, all season, the amount of shear, or the change in wind speed and direction with altitude, has been pretty close to average. Shear can tear apart a fledgling storm and can even disrupt one that is mature. In the chart below, the blue line represents this year’s shear, and the black line shows the average. As shown by the black line, there’s ordinarily a drop-off in shear during mid- to late summer. In many years that drop-off in shear encourages storm formation, but that hasn’t happened in 2022. This year’s lack of storms may be tied to a lack of instability. There just hasn’t been much to support the growth of thunderstorm clusters, which are the seeds of hurricanes.

(NOAA)

A chart of instability over the tropical Atlantic. Note the extent to which it’s running well below average.

(NOAA)

We can thank Africa for this pause.

That’s likely the result of intrusions of warm Saharan air wafting over the Atlantic and drying things out at the mid-levels. That also caps the lower atmosphere and prevents parcels of air from rising. It’s worth noting that we don’t know what the rest of the season will bring, but some models hint at an uptick in storminess come September. The forecasts for a busy season could still be right. About 80 percent of storm activity typically occurs from late August onward. The oceans are heating up and are still primed for storminess. It probably won’t stay this quiet forever.

So what we do is wait and let the days pass.