This is Tokyo and are we this bad here?

The Environmental Protection Agency has announced that it will develop plans to reduce regional haze pollution in 15 states, including Louisiana, that missed a 2021 deadline to adopt their own. The federal haze pollution regulations are aimed at improving visibility in large regions that include national parks, forests and wilderness areas. Louisiana has been required to adopt plans for one in-state area: the Breton National Wildlife Refuge, a federal wilderness area that includes the Breton and Chandeleur islands 30 miles off the coasts of New Orleans and St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes. It must also do so for two out-of-state areas: the Caney Creek and Upper Buffalo wilderness areas in Arkansas.

nola.com

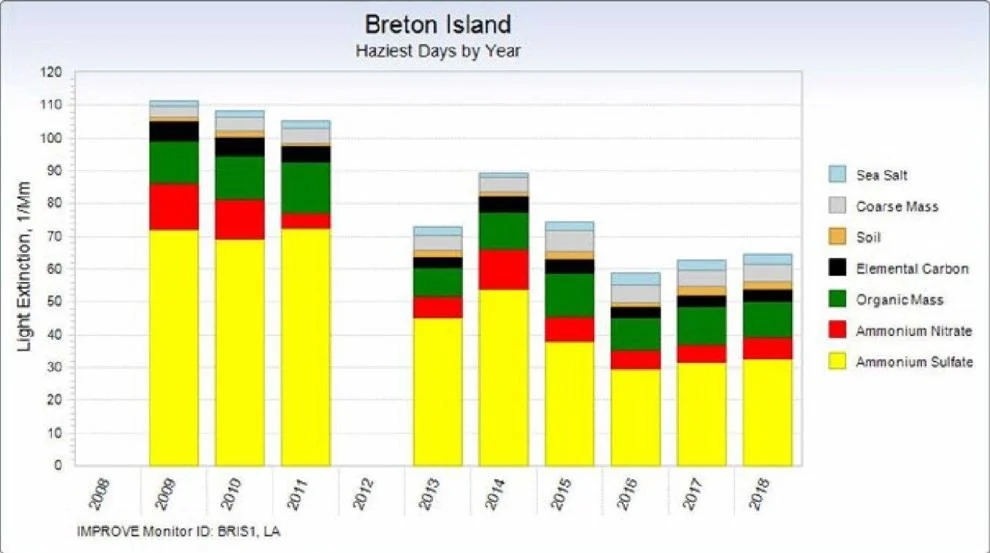

This graphic shows the change in haziest days per year at Breton Island National Wildlife Refuge, and the changes in the sources of chemicals or other materials that are causing the haze.

(Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality)

Louisiana started then stopped.

In July 2021, Louisiana halted work on its draft proposal for a haze reduction implementation plan after EPA objected to the state’s conclusion. It concluded that using the federal haze rule to further restrict the release of nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide from electric power plants, refineries and chemical plants in the state was unnecessary because other emission reduction regulations and actions were already adequately reducing the chemicals causing haze. While the haze rules are aimed at assuring pristine views in national parks, forests and wilderness areas, they also have targeted pollutants that pose health threats or odor complaints in a variety of locations. Indeed, the state Department of Environmental Quality pointed out that several of the facilities on the haze list have seen emission reductions ordered by federal and state actions under other provisions of either the federal Clean Air Act or state law. And a decision by CLECO to shut its Dolet Hills coal-fired power plant at the end of 2021 eliminated the sole facility in Louisiana that the state listed as posing a haze threat to the Upper Buffalo wilderness area in Arkansas.

There are pollution facilities through out the state.

Other facilities listed as potential sources of haze-causing chemicals that have seen nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emission reductions through enforcement of federal and state regulations include CLECO’s Big Cajun II coal-fired power plant in New Roads, and Entergy’s Roy S. Nelson and Nelson Industrial Steam plants in Lake Charles, and Ninemile Point in Westwego. In its plan, the state also pointed out that a number of refineries and chemical plants on its deferral list also have reduced emissions under a variety of other enforcement actions, including: Birla Carbon USA Inc., North Bend Plant, Centerville, Orion Engineered Carbons LLC, Franklin, Tokai Carbon CB LTD, Addis, Cabot Corp. carbon black facilities, Franklin and Ville Platte, Chalmette Refining LLC, Cornerstone Chemical Co., Jefferson Parish, Mosaic Fertilizer, Uncle Sam Plant, Convent, Oxbow Calcining, LLC, Baton Rouge, Phillips 66, Alliance, Rain CII in Chamette, Gramercy and Norco, Union Carbide Corp., St. Charles and Valero Refining, Meraux.

EPA acted after environmental groups challenged them about the reluctant states.

EPA’s action followed an April lawsuit by several national environmental organizations challenging the agency’s failure to require the states to complete plans that were originally supposed to be finished in 2018, but were delayed until July 31, 2021. In announcing it would write the state plans, EPA said that if a state submitted its own plan within two years, and the plan was approved by EPA, the state plan would suffice. The EPA notice said the agency would begin developing plans for each of the 15 states, while still allowing the states to develop their own plans. The result, that one or the other will produce a plan, “will promote greater protection for U.S. citizens, including minority, low-income, or indigenous populations, by ensuring that states meet their statutory obligation to develop and submit (state plans) consistent with visibility protection requirements.” The other states that failed to produce plans are Alabama, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia.

(EPA)

DEQ did submit a plan to public review but does not seem to have gone further.

DEQ originally submitted its draft plan to EPA and made it available for public comment on April 20, 2021. “Based upon the comments received, LDEQ is currently working on a revision and will resubmit in the future,” said Gregory Langley, a spokesman for the state agency. In its July 12, 2021 comment letter, EPA state planning and implementation branch chief Guy Donaldson said the state’s list of potential emissions sources should each have been analyzed to determine whether they needed additional control measures. While EPA’s rules “contemplates a scenario where a state concludes that no additional measures are necessary to make reasonable progress in the second implementation period, such a determination is acceptable only in rare instances, after a careful consideration of the relevant factors for its selected sources is completed,” his letter said. He recommended the state review analyses of their emissions that each facility submitted to the state “and determine what additional controls, if any, are necessary for reasonable progress.” But Donaldson also criticized the companies’ control analyses, saying several did not provide adequate information to support their estimates of how much additional controls would cost, a factor in determining whether the controls should be ordered installed. However, there have been no documents filed in DEQ’s public online database for the plan since a public comment was filed by CLECO in November 2021.

Most of the haze in the areas of minority and low-income residents.

Darryl Malek-Wiley, a representative of the Sierra Club, one of the organizations that sued EPA, pointed out that the EPA action fits with the agency’s public statements that it is attempting to address pollution problems in minority and low-income communities. “Air pollution that causes haze in our national parks originates from sources along Cancer Alley and Lake Charles, two places where big industry moved into near majority Black communities,” Malek-Wiley said. “EPA Administrator Regan saw these facilities and heard from these communities during his Journey to Justice (tour of communities). Enforcing environmental laws, and stepping in where states like Louisiana have failed to step up, is an important way for Administrator Regan to keep his commitment to these communities.”

Clean air is something we all deserve.