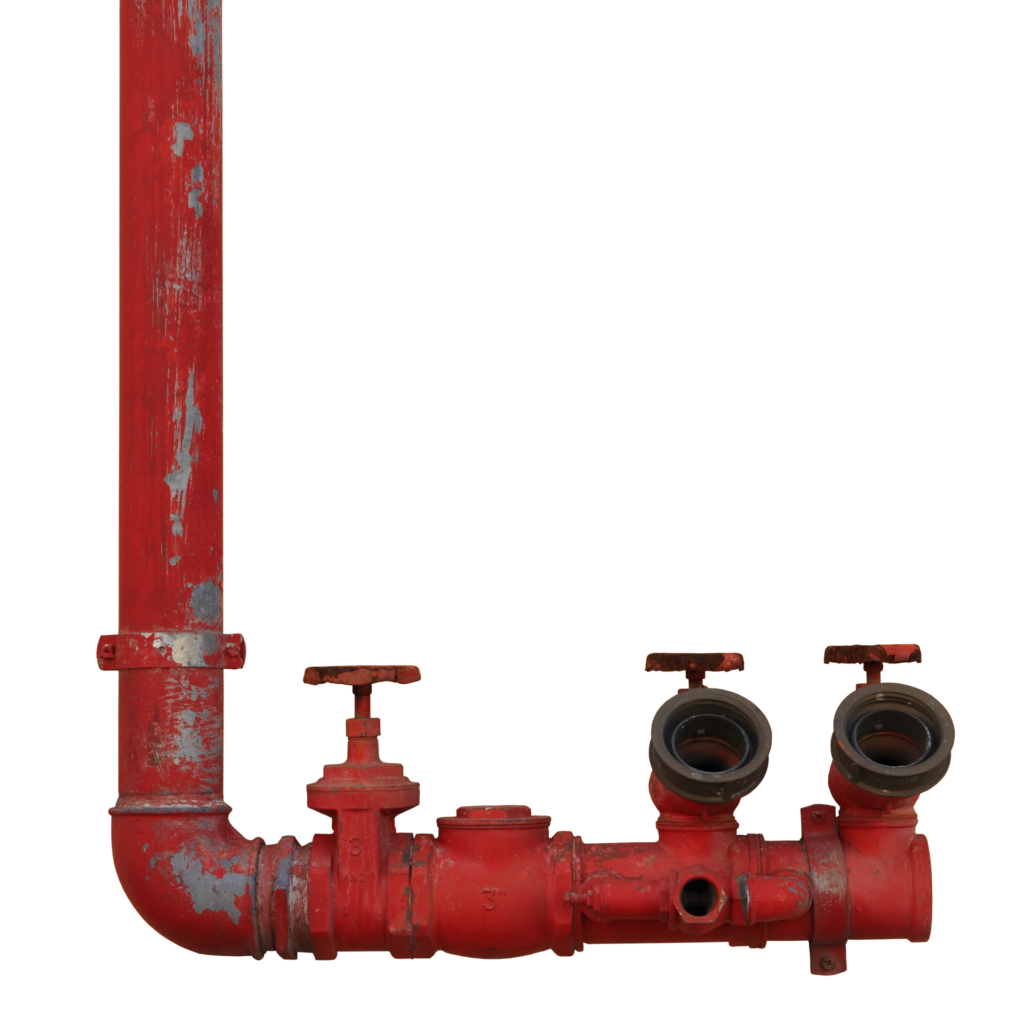

Jackson, Mississippi lost water because they did not keep up with repairs to the water systems. Are we in threat of the same?

In Mississippi’s capital city, 150,000 residents are without drinkable running water and will be for the foreseeable future after floodwaters from a swollen Pearl River caused an already struggling water plant to fail. In Louisiana, officials are looking across the state line at the crisis in Jackson with worry, and some are warning that without potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in maintenance and upgrades, water systems here could face similar problems. “There’s so many water systems so fragile right now,” said state Sen. Fred Mills, R-New Iberia. “You wonder about the life spans of their generators, their motors, their infrastructure.”

nola.com

We worry more about the pumps for flooding but how many times have we had low pressure warnings?

Many water systems around Louisiana are aging. In 2017, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimated that roughly half of the more than 1,200 water systems in the state had infrastructure that is more than 50 years old. No water system is immune: problems have afflicted some of the state’s biggest cities, including Shreveport, and some of its smallest municipalities, like St. Joseph. For many utilities, their customer base has shrunk or become accustomed to years of low water rates that haven’t kept pace with costs. Maintenance and upgrades have been deferred, meaning many of the pipes, pumps and filtration systems are decades old. New equipment is expensive, and rural communities often lack enough residents or the will to pay for it. In addition, increasingly severe storms and floods heighten the danger for older systems. Efforts are underway to address the needs.

One idea is to grade the water systems so we can see which are worst.

During the 2021 legislative session, Mills authored a bill that will see all of Louisiana’s 1,200 water systems that serve the public get a letter grade from the Louisiana Department of Health. The grades will be based on a number of factors, including water quality, infrastructure, customer satisfaction and finances. The first grades will be issued next year. “I thought the letter grade would get the public up to speed,” Mills said. But a letter grade won’t pay to repair old pipes, pumps, towers or filtration systems. The costs associated with doing that can be daunting, especially for smaller systems that lack a broad customer base.

The Jackson problem was not an overnight one but was built up over the years.

Jackson officials have acknowledged in recent days that the crisis there has been long in coming. Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba has blamed decades of deferred maintenance for the problems, and he said it could cost hundreds of millions to fix the city’s water system. Others have disputed that figure, and the crisis has generated political finger pointing from Lumumba, a Democrat, and Republican state leaders. The result of the crisis is that schools and businesses have been forced to close and the city is under federal and statewide emergency declaration. Officials have scrambled to truck in millions of gallons of water per day to meet residents’ basic needs. Even before the plant failed, the city had been under a month-long boil advisory due to concerns over the quality of the city’s water.

This might have opened up some eyes in the State.

Louisiana officials, including Mills, have begun encouraging many of the smaller systems to consider consolidation. Combining multiple smaller systems into a larger ones can spread out costs, reduce pressure to find certified staff and allow new infrastructure to be used most efficiently. “The money to support a larger group of people is going to be more sustainable,” LDH Engineer Blake Fogleman told a group gathered in Jennings to discuss rural issues last week . The law that will begin to require grading will also require water systems to submit rate studies to see if the rates they are charging bring in enough revenue, Fogleman added. “You need to prove to us that you can continue to operate,” Fogleman said. The sticks also come with carrots. The legislature this year earmarked $450 million in the budget for water and sewer system improvements and more could be on the way, Fogleman said. But he estimated are that the state’s systems need $7 billion in upgrades over the next 20 years. Fogleman called this year’s funding a “down payment” that will allow state officials to work with systems that most need upgrading. “We are starting to get out ahead of the water quality,” he said. “We are finally allowed to start looking ahead of that final curve.”

We have had a taste of this problem on a much smaller scale. But the fix was costly.

Some Louisianans got a taste of what a water crisis could be like in 2017, when the state was forced to take over the 700-customer water system in St. Joseph in Tensas Parish due to elevated levels of lead in the water. Then, the state spent nearly $10 million to replace the infrastructure, or about $19,000 per resident. There have been problems in other places as well. In St. Tammany Parish, residents served by the Cross Gates water system have complained about poor water quality that they say has led to skin rashes and other health problems. On Wednesday, the City of Shreveport issued a system-wide boil advisory after drone footage revealed there were holes in the tops of some elevated storage tanks. Around New Orleans, the maligned Sewerage & Water Board has had recurrent problems with infrastructure, though an infusion of funding in recent years has allowed leaders to make improvements and begin adding backup power systems. And Jefferson Parish struggled to get water service up and running after Ida downed so many trees that hundreds or thousands of water lines were punctured.

As a country we have neglected the infrastructure which is why the Infrastructure bill was passed.

Christopher Dalbom, a Tulane Law professor and Assistant Director at the Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy, said failing to upgrade infrastructure has had disastrous consequences in other places. Dalbom noted that poor infrastructure in Flint, Michigan allowed tens of thousands of people to be exposed to lead from the pipes that carried water. “The best thing that people in Louisiana can do … is invest in the infrastructure,” Dalbom said.

We do need to act as so many water systems are old. Yet, raising rates will upset people especially if the agency is not held in respect.