The Administration just put in effect the need for a blowout preventer and will it be good or bad? Of course there is a variety of opinions.

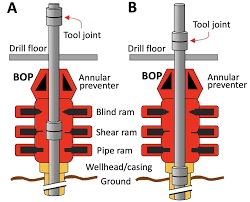

Few technical devices in oil and gas drilling may be as famous — or infamous — as the “blowout preventer.” As the name suggests, a blowout preventer is designed to seal off a well in an emergency so crude oil or natural gas doesn’t spew uncontrollably into the environment. The device gained notoriety in 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon rig’s blowout preventer failed to activate automatically during a leak, causing an explosion that killed 11 people and released millions of barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Years after the Deepwater Horizon tragedy, blowout preventers are back in the national spotlight. The Department of the Interior on Monday released a set of proposed changes to the federal regulations that dictate safety and technical standards for blowout preventers. The Biden administration’s intent is to reinvigorate the rules, which were partially rolled back in 2019 by Louisiana’s own Scott Angelle and the Trump administration. The recommended changes are fresh, so all interested parties are still taking stock of their potential impact. But battle lines are already being drawn, signaling the latest chapter in the high-stakes fight over the future of drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and beyond.

nola.com

Industry, of course, says they are not needed.

Oil and gas advocates say the regulations will be a burden on an industry that already operates under a sea of red tape for offshore platforms. Environmental justice groups, meanwhile, say the new rules are a good start but don’t do enough to address safety and oversight concerns. “I don’t think it’s going to stop the oil companies from drilling wells,” said Mike Moncla, president of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association. “It’s going to cost them more to get wells drilled and (will be) more burdensome.”

The rules go back to 2015, 5 years after Deepwater Horizon.

Nearly five years after the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the Obama administration in 2015 first proposed the “well control rule” to tighten safety standards for blowout preventers, among many other issues. The lengthy guidelines, which were officially adopted in 2016, helped to standardize technical requirements for blowout preventers and strengthen federal oversight and testing of those devices. In 2019, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement — led by Angelle, a former Louisiana lieutenant governor, Public Service Commissioner and Department of Natural Resources secretary — rolled back some of those rules, saying the requirements were too costly and too burdensome for oil and gas producers. BSEE, which falls under the Department of the Interior, oversees enforcement of the well control rule. At the time, BSEE said about 80% of the regulations were left intact. Changes included limiting the number of blowout preventer connection spots to reduce potential failure points and requiring an “array” of rams, or steel covers to cut off drill pipes to prevent releases, among other adjustments. The case was mired in technical motions when President Joe Biden took office in 2021, said Chris Eaton, a senior attorney for Earthjustice, one of the organizations that filed the suit. Biden administration officials asked the environmental groups to pause their litigation while the well control rule was being rewritten.

The new rules are under public comment now.

The new rules — which are under a public comment period until November — include requiring blowout preventers to match a well’s kick tolerance, or the maximum amount of oil and gas that can be circulated out of the well without damaging the surrounding geological formation. Should the Biden rules pass, operators will also be forced to submit failure data to BSEE instead of a third party and must start failure analyses within 90 days instead of 120, among other changes. Moncla, the LOGA leader, wasn’t critical of any one proposal in particular. However, he said the latest changes are another example of the Biden administration’s war on fossil fuels. He said the Deepwater Horizon explosion was the exception, not the norm. “There is no safer environment than an offshore rig platform. It is by far safer than working on land on a rig anywhere in the world,” Moncla said. “Everything is top-of-the-line equipment. It is state-of-the-art technology out there. It is one of the safest environments in the oil and gas industry.” Moncla said producers should still be able to “get anything they need” for the offshore rigs, but “it’s just going to be more costly to do so.”

Earth Justice does not have a position yet.

Eaton said Earthjustice doesn’t have an official stance yet on the proposed changes given their newness. But he called the proposal “a step in the right direction.” “The other thing that can be said is that it doesn’t bring it back to where it was in 2016,” he said. “It’s just simply not reinstating all of the provisions that were there.” Though he declined to speculate on why the Interior Department didn’t revive all of the killed rules, Eaton noted some key provisions that still haven’t been addressed. For example, the Biden rules don’t address testing frequency for blowout preventers, Eaton said. Under the 2016 regulations, operators had to test blowout preventers every 14 days. The 2019 changes widened that window to 21 days. “The less frequently you test something, there’s more time where you may miss some sort of component failure,” Eaton said.

Healthy Gulf and the National Ocean Industries Association also commented.

Raleigh Hoke, campaign director for Healthy Gulf, struck a more optimistic tone. He thought the Biden administration was trying to return the rules to their 2016 form. “It looks like these are bringing back some of those initial reforms, focusing on the blowout preventer systems and making sure they’re able to close at all times and that the operators of offshore facilities report failures directly to BSEE,” Hoke said. Erik Milito, president of the National Ocean Industries Association, which represents the offshore energy industry, pledged his organization would work with regulators on the changes. However, he said in a statement that the 2019 revisions addressed some technical problems and ambiguity with the 2016 rules. He added that any additional changes should follow a “similar tailored approach that does not result in unintended adverse safety consequences.”

After the public comment then the rules will come into effect.