Who lives closest to the major polluters in the state? Black communities and they pay the price.

Louisiana communities containing industrial plants and high percentages of Black residents experienced 7 to 21 times more toxic air emissions than similar locations with higher percentages of White residents, according to a new study by researchers with the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic. Those findings include the 184-mile stretch of the lower Mississippi River from just north of Baton Rouge to Plaquemines Parish that’s often referred to by environmentalists and some community residents as “cancer alley.” They include some parishes considered by the Environmental Protection Agency as having the highest risk of cancer in the nation due to air emissions. “Our study provides conclusive evidence that communities of color are disproportionately affected by industrial air pollution in Louisiana and that state environmental regulation is the driving force of this disparity,” concluded the study, which is being considered for publication in the scientific journal Environmental Challenges, but is still undergoing peer review.

nola.com

(Tulane Environmental Law Clinic)

The study is being released to the EPA to bolster their investigation of the state and the LDEQ.

The study’s lead author, Kimberly Terrell, a research scientist at the law clinic, said the study was being released now to allow its findings to be used by EPA in its ongoing civil rights investigation into permitting by the state Departments of Environmental Quality and Health. That investigation is expected to be completed in mid-December, she said. In October, EPA sent the two agencies a 56-page “letter of concern” summarizing the agency’s initial findings during the investigation of two civil-rights complaints filed in April by environmental and community groups and residents of St. James and St. John the Baptist parishes, some represented by the Tulane law clinic. EPA said the two state departments may be violating federal civil rights laws and regulations by allowing Black people to suffer disproportionate impacts from air pollution, including increased risk of cancer. One of the procedures the new study targets is the state’s decision not to be more restrictive in regulating industrial air emissions than EPA’s minimum emission standards. The result is that industries in Louisiana are not considered major pollution sources requiring installation of best available pollution control technologies unless they are emitting more than 100 tons of volatile organic compounds a year. Louisiana is joined in requiring that amount by Mississippi, New York and Texas, which have between 42% and 60% people of color in their populations.

Other states regulate better and they have more White residents, another example of racial bias.

But other states adopt a more protective 50-tons-per-year threshold, including New Hampshire, Maine and Massachusetts. Terrell pointed out those states have overwhelmingly majority-White populations, between 70 and 93%, which she says is another example of disparate impact: more aggressive regulations protecting larger White populations. DEQ spokesman Greg Langley said: “We have no comment on this Tulane study, which is undergoing peer review. We are in contact with EPA and are in discussions with them concerning resolution of any questions about LDEQ.” In an April letter to EPA responding to the environmental and community group civil rights complaints, DEQ Secretary Chuck Carr Brown argued that his agency was “an early pioneer in the environmental justice movement.” He pointed out that a 1994 report on environmental justice to the Legislature and subsequent investigations by the state and EPA found the agency had not acted improperly. He said the agency also has an internal environmental equity work group that meets regularly to discuss environmental justice and equity-related matters. Brown also said that the state’s air permitting regulatory program receives no funds from EPA. Language in the EPA regulation prohibiting discrimination says it can be enforced against “any program or activity receiving EPA assistance,” Brown argued, meaning it should not apply to the state. The state does accept EPA funds to help pay for other regulatory programs, including a recent grant to pay for new fence line monitoring of air emissions in several locations along the river and elsewhere.

That is legal speaking not moral speaking.

Brown pointed out in the letter that his department does not decide where industries are located; those decisions are made by the companies, landowners and local zoning administrators and city or parish councils. And he also cited those industries’ need for access to raw materials and land and water transportation as key reasons for their location decisions. The new study, however, concludes that despite equal access among industrial census tracts to those resources, the state’s regulatory system results in higher emissions for the tracts with larger percentages of Black residents. It looked at each census tract containing industries throughout the state, and determined that the difference in the level of emissions in Black communities was unrelated to either the infrastructure or labor supply needed for the industry. Similar access to river transportation, pipelines and railroads carrying raw materials to industrial sites, and access to industrial workers, were equally available in both census tracts with high levels of Black residents and high levels of White residents, the study found.

One-fifth of our census tracts have industry.

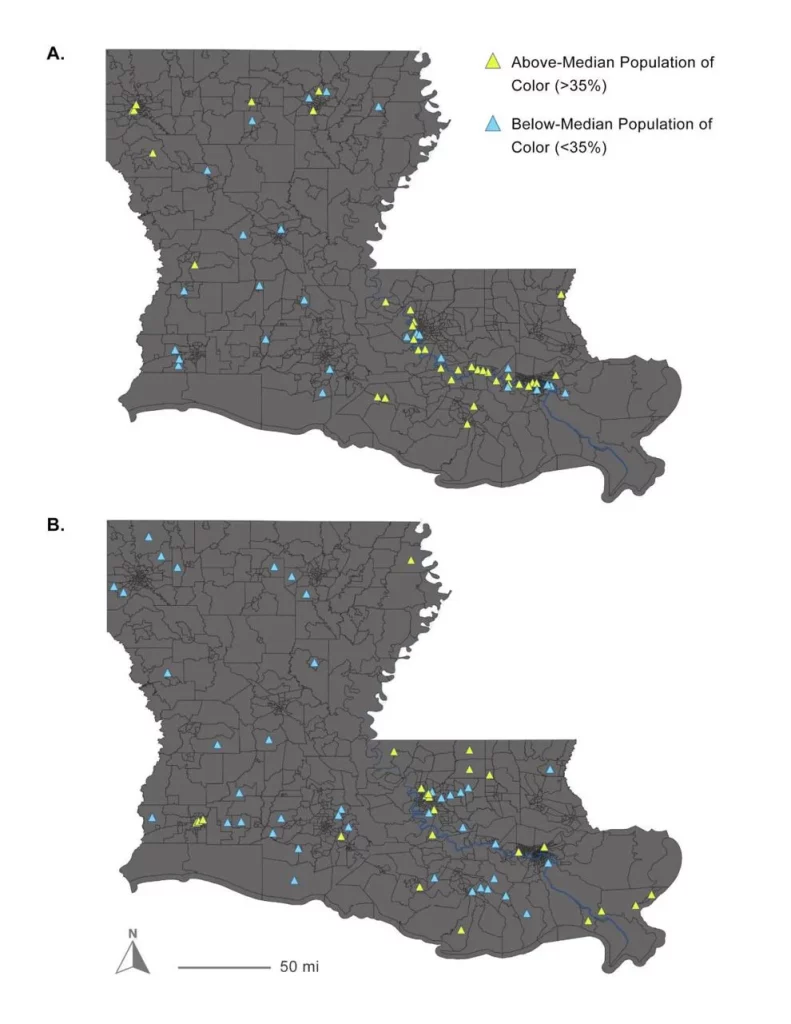

The study also found that at least one industrial facility was located in 22% of the state’s census tracts, and those tracts were more likely to contain an industrial facility if they were intersected by a railway or petrochemical pipeline, bordered the lower Mississippi River, or had relatively high proportions of their workforce, greater than 10%, employed in manufacturing. The percentage of residents of people of color residing in industrial census tracts was either similar to or lower than the statewide average of about 42 percent, except for those with railways, which had a slightly higher percentage. Eight clusters of industrial census tracts represented nearly two-thirds of tracts with industry, including the lower, middle and upper industrial corridors along the Mississippi River, Denham Springs, Lafayette, Vermilion Bay, Sterlington and Lake Charles. The river’s industrial corridor was defined as 184.1 river miles from the Big Cajun II Power Plant in Pointe Coupee Parish to the north to the Chevron Oronite Co. LLC Oak Point plant in Plaquemines Parish. “LDEQ’s own pollution inventory reveals a racial disparity that can’t be explained by industrial infrastructure,” said study co-author Gianna St. Julien, also an environmental researcher with the law clinic. “The root cause is clear – discriminatory permitting that targets overburdened communities of color for new and expanding industry.”

Why does this not surprise me? It is everywhere.