The Mississippi River Gulf Outlet was a wonderful thing until Katrina when is was a highway for water into the city.

Louisiana may finally be in line for federal money to repair widespread ecological damage from what state officials and activists have labeled a “hurricane highway” – the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet shipping channel, cursed by New Orleans residents after Hurricane Katrina. Congress looks set to approve legislation that would make clear the federal government is responsible for financing a plan to restore wetlands eroded by the now-closed “Mr. Go,” as it is often called. While the money would still need to be appropriated, settling the years-long dispute over who should pay is a major win for Louisiana officials. The provision is part of broader legislation authorizing water-related projects nationwide. A list of other Louisiana levee and flood protection projects is included. The U.S. House approved the legislation on Thursday; the Senate is expected to do so in the days ahead. The wording of the carefully negotiated legislation was not expected to change, said U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, R-Baton Rouge, who has worked closely on the issue in Congress. “Overall in terms of ecological productivity and buffer, this is an important project that needs to happen, and it is mitigating the adverse impacts of the federal project that was the MRGO,” said Graves, formerly the state’s point man on coastal restoration.

nola.com

Army Corps of Engineers

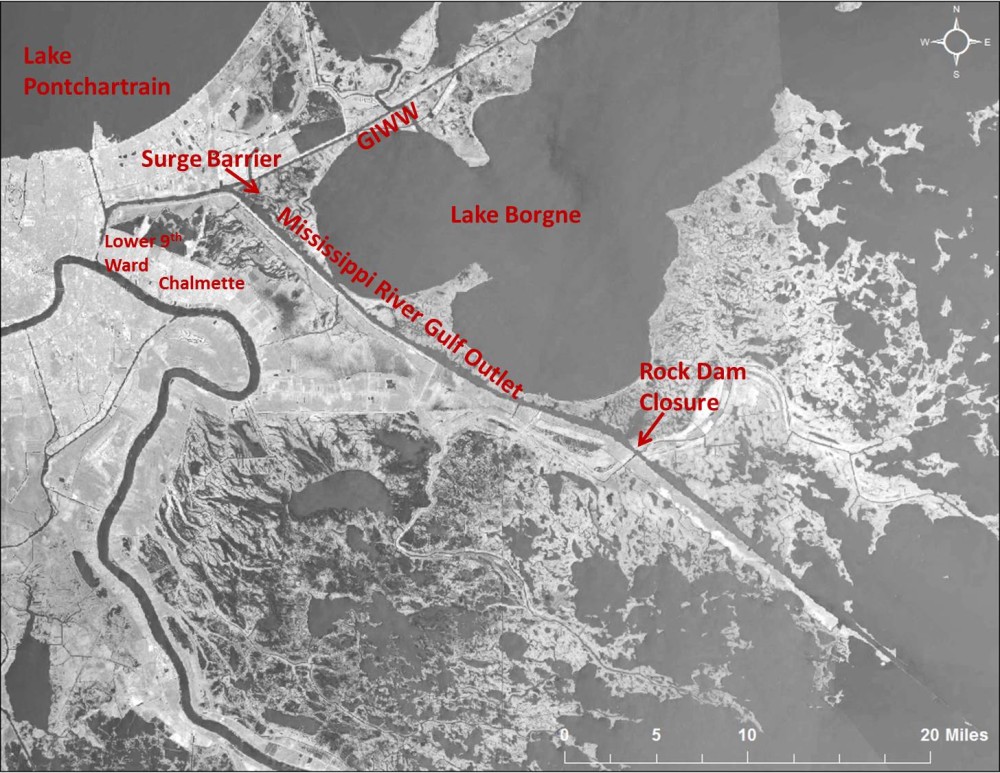

MRGO is a shipping canal to cut off the distance from the Gulf to New Orleans.

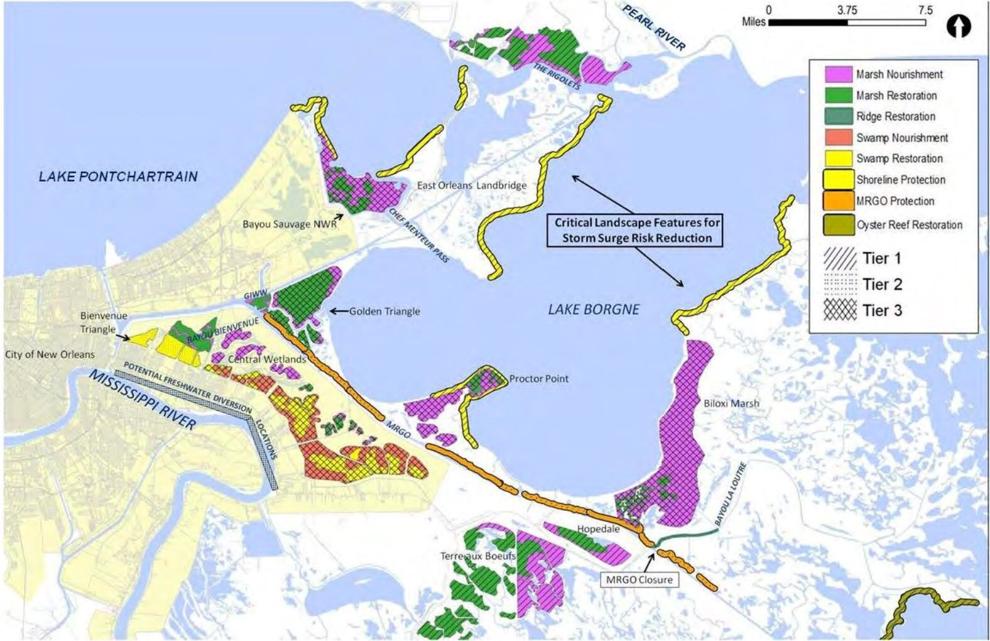

The 76-mile shipping channel, built as a shortcut from the Gulf to the doorstep of New Orleans, was labeled a “hurricane highway” by many Louisiana officials who said it funneled storm surge into New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, contributing to the levee failures that allowed the city to be inundated. The Army Corps of Engineers has downplayed the channel’s role during Katrina but, regardless, its long-term effects run much deeper. Over the decades since it fully opened in 1968, the channel has helped erode vast areas of marsh and wetlands, damaging the New Orleans area’s natural storm buffer and altering the ecosystem. Saltwater intrusion through the MRGO, which was not used as heavily as was intended by the shipping industry, has helped destroy cypress and tupelo swamp that once bordered the city. While the channel was closed in 2009 with the construction of a rock dam at Bayou La Loutre, near Hopedale, it’s been disputed who should pay for the damage it left behind, and just where those funds should come from. The Pontchartrain Conservancy, part of the MRGO Must Go Coalition of environmental, community and social justice groups, says the channel impacted more than a million acres of coastal habitat.

The Corps had a plan to rebuild some of the land but the funding dispute held up the work.

The Corps has set out a plan to restore and protect around 57,000 acres of wetlands and coastal habitat. Though that plan was estimated a decade ago to cost $3 billion, the figure is likely much higher. The payment dispute has held up plans. The Corps sought to stick to its usual formula for splitting up costs: the federal government would cover 65% while the state would cover 35%. But the state argued that previous legislation makes clear that the full cost should be borne by the federal government. A lawsuit filed by the state was ruled “premature” by a federal appeals court in 2016. The new legislation “marks a crucial milestone for addressing the disastrous legacy of the MRGO,” said Amanda Moore, director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Gulf program and coordinator of the MRGO Must Go Coalition. “More than 17 years after Hurricane Katrina, Congress has clarified its original intent – to fully and federally fund implementation of the MRGO ecosystem restoration plan.”

Just because it is approved does not mean the funding is there.

It is unclear when money for the project could be approved. It would likely come as part of a larger appropriations measure approved by Congress. Corps of Engineers spokesman Ricky Boyett said he could not comment on pending legislation, but noted that the Corps would follow the law as set out by Congress. In the meantime, the state has pursued aspects of the work, amounting to around $500 million. That includes marsh creation in various areas, such as around the new Lake Borgne Surge Barrier, the wall that’s part of the post-Katrina hurricane protection system to block storm surge.

A perfect case of the law of unintended consequences or no good thing goes unpunished.