Rising waters also hurt artifacts of our early history.

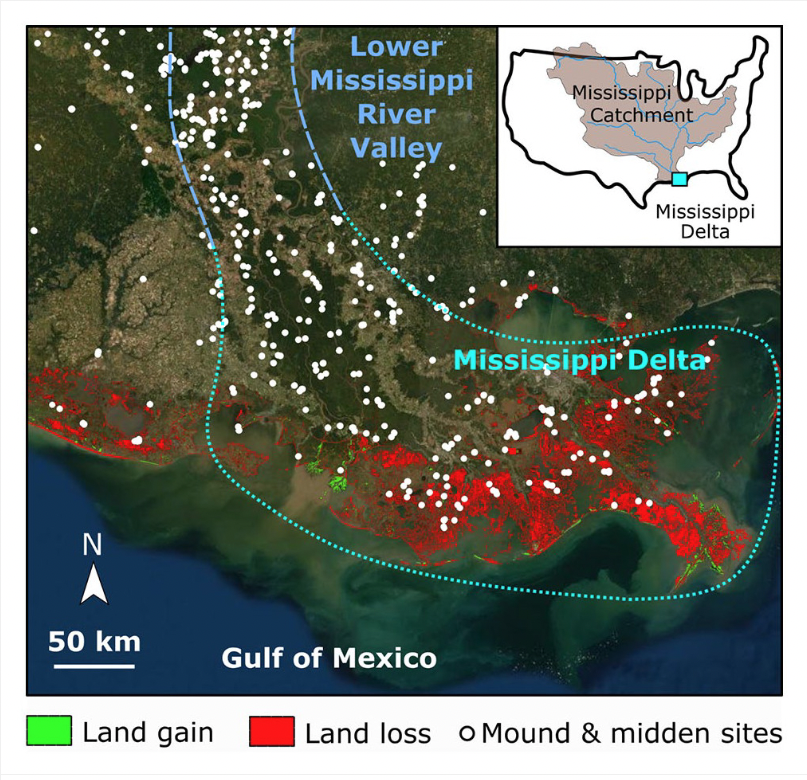

Louisiana scientists are sounding the alarm about hundreds of archeological sites that may soon be torn away by storms or swallowed up by rising seas. A new study from researchers at LSU and other universities calls for a large-scale effort to protect and study more than 1,000 ancient sites, some of which have sat along the Louisiana coast for more than 4,500 years but now face threats from climate change and rapid erosion. “You can see the destruction to some of these sites in real time,” said Matt Helmer, an LSU archeology professor and the study’s lead author. Of particular concern are many earthworks and mounds built by Native Americans around the same time the pyramids were erected in Egypt. Large mounds located near resource-rich waterways were often complex in their construction and supported settlements and villages with 500 or more residents. Some mounds served ceremonial purposes, while others had uses that still remain unclear.

nola.com

Courtesy of Matt Helmer, LSU

We are losing ancient mounds and villages every year.

Louisiana is losing an ancient mound or village site at a rate of two per year, according to Jayur Mehta, a Florida State University anthropologist and a co-author of the study, which was published in the journal Holocene. “These mound sites that are completely washing away in the span of a few decades are the first monuments that humans ever built in this landscape, and have so much left to reveal about Louisiana’s first peoples,” Mehta said. Louisiana is losing land at a rate of a football field every 100 minutes. The causes include erosion from oil and gas canals and deforestation, sea-level rise, land subsidence, hurricanes, and river levees, which prevent sediment from rebuilding coastal floodplains. Helmer said saving imperiled archeological sites requires a response on the scale of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, a federal jobs-creation program that put millions of people to work on public infrastructure, arts and education projects. In Louisiana, the WPA employed thousands of people on various archeological digs and historic documentation efforts. The excavations were sometimes clumsy or even destructive, but the scale of the work was unmatched, providing baselines for many archeological studies over the past 80 years. “Today we can do even better,” said Helmer, who also works as an archeologist with the Kisatchie National Forest. “We have new tools and technology to study the sites.” Satellite imagery, for instance, can reveal information that had once required picks and shovels.

The Tribes are not so sure of the interest as their mounds are holy.

But Native American tribes on Louisiana’s coast are wary of interest from archeologists. Many mounds are hallowed ground or contain human remains and artifacts that tribal members want to remain buried. “We feel they’re sacred,” said Theresa Dardar, a spokesperson for the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. “They were all built by hand and with the dirt carried in palmetto baskets. A lot of hard work went into them. We don’t need any outsiders fooling with them.” The tribe does, however, welcome efforts to protect the mounds. The Pointe-au-Chiens and other coastal tribes have worked with the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana to build artificial reefs near sites in Plaquemines and Terrebonne parishes. The report says such protection efforts need to be quickly scaled up. It notes that the Adams Bay Mound in southeast Louisiana, considered “ground zero of salvage archeology and preservation efforts,” has gone from completely intact and protected by a marsh to partially submerged within 25 years.

The ancients knew about the water and what it could do.

The Louisiana coast’s ancient cultures were savvy adapters to a landscape often in flux from storms, flooding and the Mississippi River, which regularly changed its course until it was constrained by levees. Potential lessons for living with today’s changing coast could disappear unless research and protection efforts are given a substantial boost, Helmer said. “We’ve only scratched the surface of what we can learn,” he said. “If we don’t invest now, all this knowledge will be lost.”

We need to learn history both for the knowledge we can gain but also to see what not to do in the future.