Formosan termites have infested the French Quarter for a while. They are declining.

There’s good news in the air for French Quarter residents as Mother’s Day approaches: Eleven years after the end of the experimental program to install termite-killing baits throughout the riverfront neighborhood, at least half of the area’s buildings still are being treated for Formosan termites — at homeowners’ expense — and their numbers seem to be dropping, according to the New Orleans Mosquito, Termite and Rodent Control Board. And although a similar comprehensive treatment program for the state-owned Jackson Barracks National Guard compound has been in effect for only eight years, Formosan termite intensity seems to be dropping in that area, too, said Carrie Cottone, assistant director of the New Orleans pest control agency. However, termites from nearby neighborhoods that are not part of the treatment program are continuing to be found in Jackson Barracks. “We have observed the swarming termites have actually decreased in the French Quarter over time,” Cottone said during a recent interview. “That was the exact opposite of what we had expected, which sometimes in science happens that way.”

The US Department of Agriculture was involved.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Southern Regional Research Center kicked off “Operation Full Stop,” a $5 million-a-year experiment to see if treating every building in a neighborhood with the newest termiticides could halt what seemed to be an effort by the invasive Formosan subterranean termite to eat every wood structure in the Vieux Carre. In 2011, a decision by Congress to end “earmarks,” line items introduced into agency budgets by individual members of Congress to finance pet projects, and an earlier brush with an economic recession, brought a halt to the federal agency’s payments of between $750 and $1,000 a year to building owners for termite treatments in the neighborhood. The Full Stop program included homes and businesses between Esplanade Avenue and Bienville Street, and North Rampart Street and the Mississippi River, about three-fourths of the Quarter’s buildings. The program also treated buildings and open spaces in a triangular area along the river, including the Public Belt Railroad, the French Market and the U.S. Mint. Formosan termites were accidentally brought back from southern China to the New Orleans area at the end of World War II, stowaways in wood shipping crates used to return military equipment to Navy facilities then along the river in Algiers, and National Guard facilities on the lakefront near the University of New Orleans. Alates, the winged, reproductive caste of the insects, crawl out of their nests between April and July to fly about 300 feet and meet up with another alate to attempt to create a new colony. In the New Orleans area, the biggest swarms of alates have historically occurred on the same weekend as Mother’s Day, which this year is on May 14.

The termites are particular when the swarm.

The termites leave their nests at dusk when the temperature goes above 80 degrees, humidity reaches 90% or greater, and winds are calm. In the wild, they use the moon as a cue to fly away from the nest; in New Orleans and other communities, they also fly to streetlights and porch lights, and to lighted windows. The alates lose their wings when they hit the ground and then search out a partner. A pair can create a new nest in as little as five years, both by burrowing in the ground, or by finding a moist spot in wood in a building above ground. Unlike the native subterranean termite that formerly was the most common in Louisiana, as long as they have a source of moisture, they don’t need a connection to the ground. The use of termite baits in the Quarter — pieces of wood treated with a termiticide and installed beneath metal caps found on the sidewalks in front of buildings — have proved to be successful in reducing the termite’s damage, which at one time was estimated to total as much as $300 million a year in the New Orleans region. Worker termites search out the wood baits and bring them back to their nests, where they are fed to — and kill — the queen, which can take several months to be successful.

How do you determine that the swarms are less.

Mark Janowiecki, a research entomologist with the board, has been trying to find out why the Quarter’s termite populations are continuing to drop by testing the genetic history of alates caught on sticky traps. What he’s found is that the vast majority of them can be matched to about six family nests, a good indicator that the continued treatment of the Quarter is limiting the sources of new termites that could create new nests. Similar testing at Jackson Barracks has found alates matched to 20 or more different colonies. “We have all the buildings under control there, another areawide control program,” Janowiecki said. “But despite eliminating the termite colonies in the Jackson Barracks buildings, we still had a lot of swarmers and they’re from a lot of different colonies. “We think that is because the Jackson Barracks is a long and narrow area, so there’s a lot of alate flow coming in from the areas around it,” he said. The good news for the Quarter, Cottone said, is that at least half of property owners have agreed to pay for continued treatments. “Which is fantastic,” she said. “People really do take this seriously, and I applaud them for keeping up with those termite contracts so long after the Full Stop program,” she said.

(LSU AgCEnter)

Termite activity is high and is moving northward.

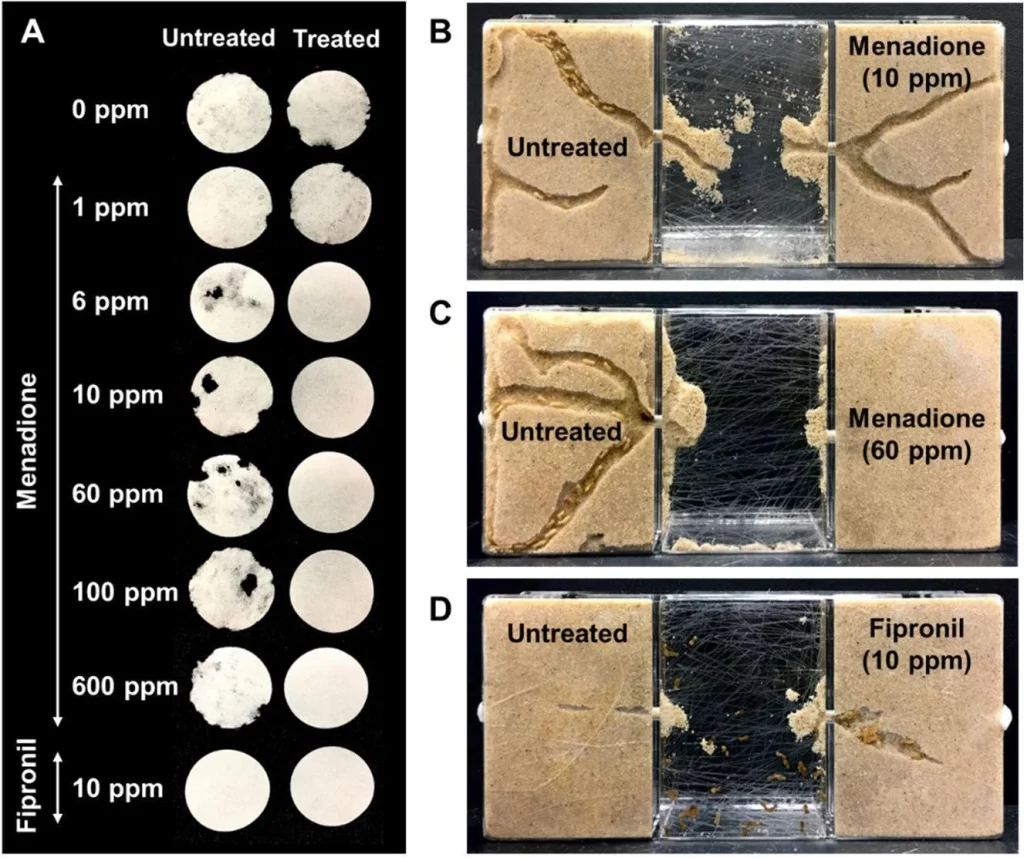

Termite activity still remains higher in other areas and is continuing to expand northward across the state. The Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry’s director of structural pest control said this week that pest control operators have actually reported treating for Formosan termites in every parish of the state. The operators are required to file a record of every building they treat and the insect for which they’re treating. LSU entomology researcher Qian “Karen” Sun has been focusing her work on the potential development of a new termiticide using synthetic vitamin K3, also known as menadione. In a 2021 scientific paper, Sun and fellow LSU researchers Roger Laine, Paul Castillo and Kieu Ngo outlined how the new chemical had many of the termite-killing properties of fipronil, a popular termiticide that does a good job of killing termites but also has been linked to the worldwide damage to honeybees, including “colony collapse disorder,” in which bees lose the ability to communicate. Based on the study results, Sun and Laine believe that menadione would not be a worthwhile replacement for liquid termiticides used to treat buildings, and are now looking at whether the chemical can instead be used as a treatment for wood used in building construction.

Get rid of them al!