Aren’t they cute? Put them in the wild and roaming free and the cuteness fades, fast.

They attacked Shakira in Barcelona. They’re “rampaging” in San Francisco. In November, they appeared in New Orleans East, tearing up yards and putting residents on edge. Proliferative, destructive, and seemingly irrepressible, feral hogs have rapidly become one of the most challenging invasive species on the planet. Once primarily a nuisance in rural areas, the “pig bomb,” as South Carolina-based feral hog expert Jack Mayer calls it, has arrived at the doorsteps of cities like New Orleans. “The urban incursion by wild pigs is kind of a global phenomenon right now,” Mayer says. “Hong Kong has a major problem, Rome, cities across the globe—in part because populations have grown to the point that they’ve expanded into developed areas.”

nola.com

There are a lot of them covering most of the state and a growing problem.

Approximately 900,000 feral hogs currently roam Louisiana, across all 64 parishes. They reach sexual maturity between 6 and 8 months of age and can produce up to two litters of as many as a dozen piglets a year—meaning the latest population figures are outdated almost as soon as they’re published. The Louisiana State University AgCenter estimates that feral hogs cause $76 million in agricultural damage annually in Louisiana, destroying everything from sugarcane to rice to corn, and their rooting behavior also damages levees. Known as “opportunistic omnivores,” they outcompete many native species for resources, prey on animals as large as baby deer, and even threaten alligators by destroying their nests and eating their eggs. They also can carry dozens of viral and bacterial diseases, many of which can infect humans and livestock. On top of all that, feral hogs are highly intelligent animals that will defend themselves if threatened. Local hog hunter John Schmidt, better known as Trapper John, puts it succinctly: “They’ll fight till their last breath.” If they’re not fighting, they’re hiding, and they’ve proven quite adept at eluding capture in the forests and swamps of Louisiana—in part, because they’ve had a nearly 500-year head start.

Blame the Spanish explorers as they brought them over. That was how long ago?

It began with an invasion of another kind, when in 1539 Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto brought soldiers, enslaved people, horses, and as many as 300 domestic hogs into the territories of various American Indian tribes in what is now the Southeastern United States. Historians generally agree that this was the first time pigs (domesticated or otherwise) appeared on the North American continent. Sus scrofa—the scientific name for all wild and domestic swine—helped sustain many European colonization efforts due to their ability to reproduce quickly and adapt to a wide range of environments. When de Soto died of an illness on the banks of the Mississippi River in either present-day Arkansas or Louisiana in 1542, his herd of pigs had already grown to 700, and along his 3,000-mile journey many of the animals had escaped or ended up in the possession of local tribes. Spanish colonists knew they had a pig problem long before de Soto’s ill-fated trek. The species had first been introduced to the Caribbean in 1493, when Christopher Columbus brought eight domestic swine to the island now known as Cuba. Columbus’s hogs quickly multiplied and were used to stock islands throughout the Spanish West Indies. Their ever-growing herds soon began terrorizing the islands, destroying maize and sugarcane crops, killing cattle, and even attacking people. Still, de Soto and many colonists after him took hogs from this stock with them on their voyages throughout the region.

The Spanish might have been first but also blame the French and English who came to settle.

The Spanish were joined in transporting hogs to North America in the coming centuries by English and French colonists, including René-Robert Cavalier, sieur de La Salle, and Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, who brought hogs to Biloxi in January 1699. Many of these hogs and their offspring went feral because owners typically allowed them to range freely without fencing. These wild populations found cover in the forests, at the edges of human habitation, and reproduced unchecked. By the 19th century, feral hog populations in the Southeastern US had become a well-established nuisance. The backyard pig once seen as a reliable source of food had evolved into something else: a mythical menace of the woods. Newspapers enhanced stories of close encounters on the home front with fantastical yarns of wild boar hunts carried out by European royalty. Those who could bag a boar with sizable “tushes”—slang for tusks—returned to a hero’s welcome. The Daily Picayune described one such homecoming on its front page on February 2, 1876, detailing the “splendid capture” of a 275-pound boar near Fort Macomb. Its brave captors, identified as H. Montreuil and A. E. Livaudais, proudly displayed the boar’s head at the Gem Saloon on Royal Street. The paper promised, “There are doubtless many more wild boars on the prairie, and further splendid sport is expected.”

Pig, hog and now boar? Which are they?

“Boar” is the technical term for all adult male swine, but it began carrying a notable distinction as hunting feral hogs for sport became more popular in the U.S. The animals hunted by European royals were likely actual Eurasian wild boar—the progenitor of all domestic and feral hogs. Though it’s the same species, the Eurasian boar bears notable physical differences from its descendants. Pure Eurasian boars tend to have darker and coarser fur, longer legs, larger heads, and, importantly, bigger tushes—er, tusks. “If you have a choice between shooting something that looks like a scrawny Hampshire boar or a Eurasian wild boar,” Mayer says, “you’re gonna want the Eurasian wild boar.” Despite the casual use of “wild boar” in media accounts of hog hunts in the United States in the latter half of the 19th century, the first documented introduction of pure Eurasian wild boar in the country didn’t occur until 1890, when millionaire Austin Corbin imported 13 boar from Germany to his private reserve in New Hampshire. Thus began a wave of wealthy white men importing Eurasian wild boar onto their vast estates: Edward H. Litchfield in New York in 1902, George Gordon Moore in North Carolina in 1912 and in California in 1924, Leroy G. Denman Sr. in Texas in 1919, and more. These wealthy hunters, ironically, became the feral hog’s best friend, popularizing a sport that relied upon healthy populations. Meanwhile, their boars—as they are wont to do—got out. And multiplied.

With no enclosures and brought over to be hunted, they became feral and were probably better and harder targets. Better for hunting.

Free from their enclosures, these Eurasian boar met members of the established S. scrofa population in the US and, being almost genetically identical, began producing hybrids that over time picked up the best traits of their ancestors and spread like wildfire. “Hybrids get this two-part coat where they can survive in the snow and can live on the equator,” says Buddy Goatcher, a wildlife biologist with more than four decades of experience trapping and hunting wild hogs in Louisiana and elsewhere. “They’re super survivors.”

Finally realized as being a pest, changes were made.

To help fight back against suddenly booming feral hog populations in the early 20th century, Eastern and Southern states passed livestock fencing laws that in many areas ended free-ranging practices that dated to the early colonial eras. A 2014 federal report co-authored by Goatcher noted that “during the Great Depression (approximately 1930–40) and following decades, wild pigs were almost eradicated, except in those wards, parishes, and counties where government officials and local statutes protected pig free-range practices.” By the early 1960s, there were only 7,500 feral hogs in Louisiana—less than one-hundredth of today’s total—largely contained to areas with longstanding free-range populations, such as in the vicinities of Catahoula Lake and the Pearl River.

The hogs fought back!

Despite these initiatives, feral swine found a way to bounce back, with some help. The Eurasian wild boar still enchanted wealthy sportsmen, and Leroy Denman’s Powderhorn Ranch on the Texas Gulf Coast had plenty of them—too many, it turned out. Dennis Good, an avid outdoorsman from Belle Chasse, recalls in the early 1970s being invited to hunt boar that had escaped from Powderhorn onto his friend’s 10,000-acre ranch in Victoria, Texas. Good got more than a hunt: the friend offered to load up a cattle trailer and send Eurasian wild boar back to a pen Good had set up in Chalmette. Good, now 80 years old, says he intended to transfer the boar to another friend’s private property in Mississippi, “but the majority of them escaped through the fence, and thus populated Verret, and the levee, and New Orleans East.” “That’s how the Russian boar stock got over here,” Good says. “I hate to say it, but it was me.” Though there has been significant interbreeding with feral hog populations at this point, experts agree that the approximately 17 Eurasian wild boar Good brought into Chalmette in 1973 account for essentially all the Eurasian wild boar and related hybrids in Louisiana today, most of which can be found in the marshes east of New Orleans East.

There are specific characteristics of these boars but Chalmette was not the only source.

Those animals stand out for their Eurasian wild boar characteristics, but many other hunters participated in spreading feral hogs descended from domestic stock throughout the state in the ensuing decades, as they realized they could have the thrill of the hunt on their own private property without having to travel long distances or deal with public land regulations. “You took an animal that can reproduce exponentially and just planted the seeds like Johnny Appleseed across the state,” says Jim LaCour, state wildlife veterinarian for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. Louisiana allowed free-ranging domestic hogs in 14 parishes until 2010 and didn’t begin limiting the transportation of feral swine within the state until 2016. Even with tighter regulations today and looser restrictions on hunting, LaCour says that the state is routinely falling well short of harvest benchmarks needed to keep numbers in check. Hunters would need to eradicate roughly 75 percent of the population annually, but in recent years the harvest has routinely been below 40 percent. Last year, however, Louisiana hunters took out 625,000 hogs, a spike LaCour says might be a temporary and unusual consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. More people off or out of work might mean more time spent in the wilds hunting.

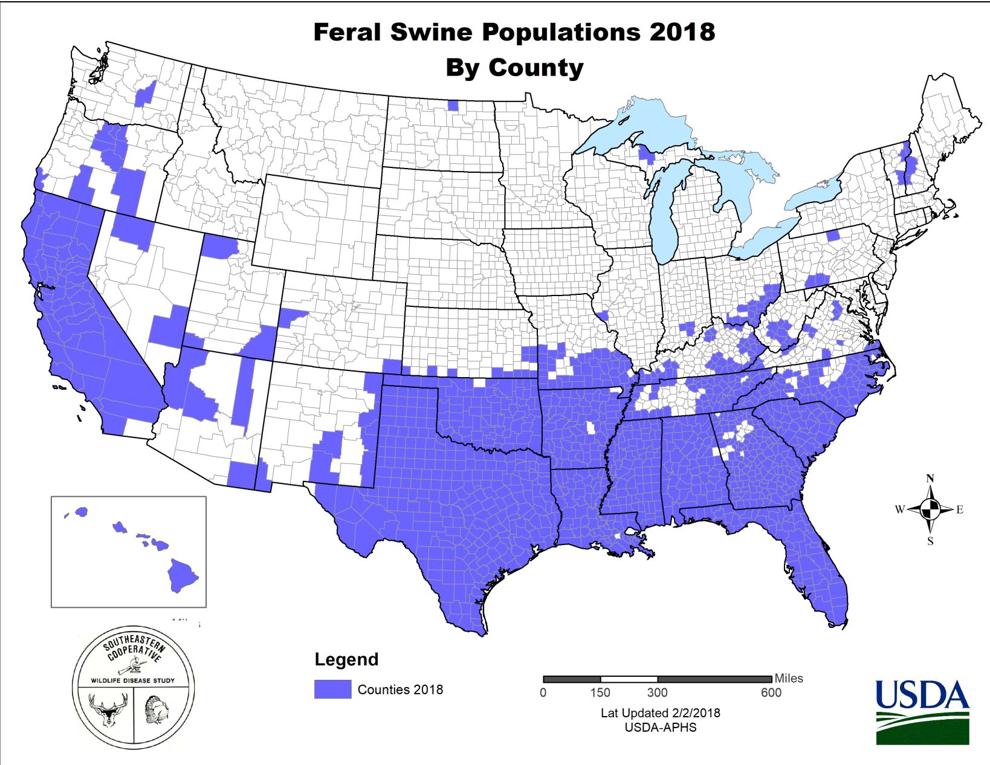

U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA

This is one case where gun restrictions hurt. There are exemptions in New Orle\eans East but not for hunting boars.

Mitigation is complicated for residents of New Orleans East because of a longstanding Orleans Parish law against discharging firearms. (The statute lists some areas of exception, largely in the marshes east of the city.) In November, WDSU’s Sherman Desselle reported on feral hogs tearing up yards in Oak Island, a neighborhood once envisioned as the first of many eastward expansions of New Orleans East, now isolated between the abandoned Six Flags and the swamp. After Desselle’s report came out, he says he received a number of calls from local officials and feral hog hunters trying to learn more about the problem in Oak Island. The next day, a hunter came out and gave a trap to the resident that reported the issue. “Situations like that remind us that unfortunately people can’t always rely on state and local officials to fix a problem,” Desselle says. “Sometimes the best help somebody can get is from a neighbor.”

I saw many shows were, in Europe, they hunted boars. None showed the problem we have here. This story is an excerpt from a post on The Historic New Orleans Collection’s First Draft blog. Visit hnoc.org/firstdraft to read more.