Every state near us has a limit in pogy’s, or menhaden, catch. We don’t and so we are taking them by the boatload.

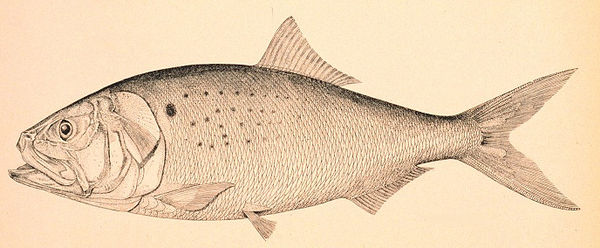

Along a chain of islands stretching from Venice to Grand Isle, a silvery swarm rises from the depths and flashes in the eye of a passing pelican. When the bird splashes down, scooping a mouthful of dollar-bill-sized fish, a feeding frenzy breaks out. Gangs of dolphins charge in, as do larger fish and dozens of other seabirds, all vying for a taste of a stinky, oily fish known as menhaden. The dolphins are smart enough to flee when the Gulf of Mexico’s apex predator arrives, first with a fish-spotting airplane and then a 174-foot-long “mothership” bearing two smaller boats that slide from a ramp and begin to encircle the scrum of sea life in a long black net. Steering his boat around the net, Venice-based fishing guide Michael “Red” Frenette gives a play-by-play of an industrial fishing process he says is harming his business and Louisiana’s fragile coastal ecosystem. Pound for pound, menhaden, also called pogy and fatback, is by far the state’s largest fishery. Yet few Louisianans have heard of it, and fewer still know how it’s fished. Frenette has witnessed the process dozens of times, and it still makes him furious. “They want the little fish, but they’re taking everything,” he says as the fishing crew cinches their purse seine net from the bottom and then tighten its top. Frenette points out a saltwater catfish and several burly redfish struggling amid the compressing mass of menhaden. He’s seen panicked dolphins tangled in the nets; today he spots a pelican. The bird dangles by its beak, wings flailing, as a winch lifts the net out of the water. A crewman yanks the creature free just before its head is crushed in the machine.

nola.com

Once the fish are on boad efficency takes over.

The fish are sucked via a vacuum into the mothership’s million fish-capacity hold. It’s a fast, efficient process, but for Frenette, it’s the marine equivalent of a clearcut or a strip mine. “But that’s what this state’s all about,” he said. “If it’s oil or it’s fish, we allow companies to take, take, take.” There’s growing concern that all this taking, focused on the shallow waters within a mile or two of the shore, is weakening the food web on which much of the Atlantic ecosystem relies. “They’ve been described as the most important fish in the sea,” Skyler Sagarese, a research scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said of the humble menhaden. “They’re important because of their economic value, but also because almost every predator — marine mammals, birds, sea turtles and (bigger) fish — eats them.” If there’s a fish you like to eat, chances are it likes to eat menhaden. As for direct human consumption, Frenette wouldn’t advise it. “They’re nasty,” he said. “They’re pretty much all oil.”

Gringing them up though, makes then useful for many uses including some we use

And bones. But that combination makes them great for grinding up for a variety of industrial uses. Much of the menhaden catch becomes fertilizer, pet food and livestock feed. Menhaden’s been used in lipstick, linoleum, paint and machinery lubricant, but the industry’s recent growth has been in the human health and nutrition market. Rich in omega-3 fatty acids, menhaden is pressed into pills and slipped into a range of foods — granola bars, pasta sauce, margarine — all of which can then advertise the bankable nutrient. The industrial-scale menhaden fishing allowed by Louisiana isn’t welcome in other Gulf states. Florida and Alabama have banned it entirely. Mississippi won’t allow it within a mile of its shores. Texas has half-mile and one-mile buffers and a strict catch limit that have effectively killed the industry in the western Gulf. The menhaden industry once ranged along much of the East Coast, but only Virginia allows it now, albeit with ever-tightening catch limits and harsh penalties when the industry breaks the rules. But in Louisiana, the industry has free rein. The state has dozens of rules for its other commercial fisheries, but menhaden ships can fish where they want and take as much as they want. The state leaves it up to the industry to report their catch numbers, both for menhaden and other species unintentionally snagged as bycatch. Even by the industry’s own estimates, the unrestricted haul is immense. About a billion pounds of menhaden are caught in Louisiana waters each year, making it by far the biggest fishery in the state and the Gulf by weight. Taken together, Louisiana’s better-known catches — shrimp, crab, oysters and crawfish — don’t amount to half as much.

This freedom to catch as much as you want may be changing s the legislature is considering a bill to regulate the industry.

A bill winding its way through the Legislature aims to put the first substantial restrictions on the industry. House Bill 1033 would cap the menhaden catch in Louisiana waters at 573 million pounds per year — a substantial reduction from the more than 1 billion pounds caught in recent years. And only 20% of that catch could be taken within a mile of the coast — an area considered the sweet spot for catching menhaden, but also for the redfish and trout targeted by recreational fishers. The bill would also require menhaden vessels to file daily reports on catch amounts and locations, creating a level of accountability that the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Joseph Orgeron, R-Larose, says has been sorely lacking. “Every other fishery has more checks and balances,” Orgeron said. “We have none of that for menhaden. It’s an all-encompassing, indiscriminate catch.” Orgeron’s last attempt at regulating the industry would have created buffers similar to Mississippi and Texas. It died when it reached the Senate last year. He said the same challenges loom for this year’s bill: “Strong lobbies, big companies.”

With spotter planes and word of mouth it is hard to keep a big catch secret.

Word spread quickly about the big catch Frenette witnessed near Scofield Island on a recent afternoon. Within an hour, another spotter plane and four more ships chugged into view and began deploying net boats. Once full, the ships head to the docks at the Daybrook Fisheries processing plant in Empire, a small south Plaquemines Parish community that’s been hit so many times by storms that little remains but a church and the plant’s sprawling pipes, stacks and steel-clad warehouses. Owned by Oceana Group of South Africa, Daybrook is one of two foreign-owned companies that make up Louisiana’s entire commercial menhaden fishery, valued at $80 million annually. Omega Protein, owned by Cooke Seafood of Canada, owns the state’s other plant, south of Abbeville on the Vermilion River. While the Empire plant is plenty busy, processing 40% of the annual Gulf menhaden catch, Daybrook warned that Orgeron’s bill could force it to shut down. With a catch limit, “I go out of business; the factory goes out of business,” Francois Kuttel, Daybrook’s fleet manager, told lawmakers last month. “It’s as simple as that.” Supporters say the loss of the plant’s 300 full-time jobs would cripple south Plaquemines’ already struggling economy. Storms and erosion have decimated the parish’s once-thriving citrus industry and the oil industry has been pulling up stakes, most recently the Phillips 66 Alliance refinery, which laid off 470 people earlier this year. “Lord knows we cannot lose this factory,” John Helmers, the parish’s coastal resources director, said of the menhaden plant. “It is one of our last lifelines.”

This law will impact communities all along the coast.

State Sen. Bob Hensgens, R-Abbeville, also worries about putting limits on one of the largest employers in Vermillion Parish. The Omega plant provides about 270 jobs and bolsters several local businesses, he said. A recent report commissioned by the industry estimated the menhaden fishery supports 1,425 jobs in Louisiana and Mississippi and pays $13.7 million in business taxes each year. Underscoring the fishery’s dependence on nearshore catches, the report notes that two-thirds of its value derives from state waters, which extend 3 miles from the coast. But the industry’s economic benefits have come at a price. Plaquemines health officials and environmental groups have been raising alarms about the Daybrook plant for decades. Daybrook’s own safety and environmental manager filed a lawsuit in March alleging that the plant willfully spews large amounts of fish waste and chemicals into the Mississippi River and other nearby waterways and has resisted taking basic precautions to avoid spills. Daybrook has not responded to several requests for comment. Omega’s Abbeville plant has been the source of odor complaints from towns more than 20 miles away. Among its environmental violations was a $1 million fine in 2017 for twice dumping large volumes of polluted water into the Vermilion River.

The industry has paid fines and has a perfect enemy that is costing them the money.

Omega’s Abbeville plant has been the source of odor complaints from towns more than 20 miles away. Among its environmental violations was a $1 million fine in 2017 for twice dumping large volumes of polluted water into the Vermilion River. In 2019, Omega agreed to pay $1 million to resolve allegations that the company obtained a government loan by falsely certifying compliance with clean water laws. Omega spokesman Ben Landry said a poor judgment by individuals were to blame for some of the company’s more high-profile run-ins with regulators. “We bit the bullet as far as (fines),” he said. “We’re a much cleaner operation, I promise you that.”

The sport fishing industry says this is a good bill.

Sports fishing advocates, which strongly support Orgeron’s bill, argue their industry offers more to the economy while doing less harm to the environment. The business of outfitting and guiding anglers supports at least 5,300 jobs in Louisiana and pumps about $339 million into the state, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Commerce. “People spend a lot of money to do recreational fishing in Louisiana,” said Chris Macaluso, marine fisheries director for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “They’re shocked when they see this large-scale industry taking place in some of the best places in the world to catch an iconic species — redfish.” Menhaden ships sometimes beat out sport anglers at catching redfish, even though they’re not trying to. “Guys are fed up seeing the aftermath of those menhaden ships, with sometimes 50 redfish dead in the surf or washed up on the beaches,” Macaluso said. Omega, which does not publicly disclose its fishing data, says it keeps bycatch below 5% of their total catch. But when the industry is hauling in a billion pounds of fish from Louisiana waters, the fraction of bycatch could amount to 50 million pounds of other species. That’s 15 times larger than the state’s combined commercial catch of tuna, mackerel, and snapper. Several fish species, including speckled trout, amberjack and grouper, have suffered population declines in the Gulf, but other factors, including anglers themselves, may be to blame, Landry said. “You can’t put everything on this fishery,” he said.

A hearing is desaired but the fear is that emotion will be displayed not facts.

As chair of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, Hensgens will decide when or if the bill will have a hearing, a critical step before it goes to the full Senate. While he wants the bill to be heard, perhaps later this month, he said the debate has been too “driven by emotion.” “Sometimes we see a pogy boat and then we can’t catch any fish,” he said. “Are the boats taking the fish? That could be happening, but we need the data to tell us that.” Scientists agree that good data on Gulf menhaden is sorely lacking, but there’s no doubt that menhaden are a uniquely important species. Menhaden tend to congregate near estuaries, where they gobble up vast quantities of plankton, which can improve water quality and may help beat back the algal blooms at the root of the Connecticut-sized low-oxygen “dead zone” that has long plagued the Gulf. Menhaden turn those drifting particles into billions of calorie-packed, bite-sized bodies that transfer an immense amount of energy up the food chain. “They’re our equivalent of eating two Big Macs,” said Kelly Robinson, a marine scientist with the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Over fishing is not a concern but the fish that depend on them for food may be the ones who suffer.

There’s little concern about menhaden being overfished. Even when their populations are sharply depleted, the fast-breeding fish is quick to recover, but the bigger animals that eat menhaden may go hungry, say sport fishing groups. There’s disagreement on whether there’s enough data to support the idea that menhaden are filling the bellies of other Gulf species. When scientists have looked at the stomach contents of redfish, red snapper and other Gulf predator fish, they’ve found relatively few menhaden. Based on this data, Robinson believes reducing the catch by half would offer some benefit to other species, but not enough to justify the economic impacts. However, Sagarese, the NOAA scientist, notes that most Gulf fish stomach studies were conducted during years of especially large-scale menhaden fishing. Fish might not have appeared to be eating much menhaden because the industry was already netting so much of it. “We are definitely underestimating the consumption of menhaden,” she said.

There are other areas of the country that have gone through this effort before so they ccan be an example of wht to do and what the effects are.

Chesapeake Bay has a longer history with the menhaden industry and a richer pool of data showing menhaden’s immense value to other species, said Chris Moore, an ecosystem scientist with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. But if you want to know what fish are eating, you don’t have to rely on scientists like him. Just ask the people catching fish, he said. Chesapeake anglers sounded the alarm when they started reeling in emaciated bass that weren’t finding enough menhaden to eat. “Anglers are out on the water seeing this everyday,” Moore said. “They can help your legislature understand what’s happening in your ecosystem.” Other Gulf states turned anglers’ concerns into regulations that sharply curtailed the menhaden industry. Texas decided more than a decade ago to pass catch limits and other restrictions that sent its menhaden industry packing. “This is a big issue, and it’s going to spread here,” Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Director Larry McKinney said in 2008. “Why don’t we just stop that now?” In 2016, Jackson County joined Mississippi’s two other coastal counties in prohibiting menhaden fishing within a mile of the mainland. “I support your business,” a county commissioner told Omega representatives at a meeting. “But let’s move it out and conserve our resources so people in the future can fish too.” Macaluso is embarrassed Louisiana is trailing other Gulf states in putting conservation ahead of the menhaden industry. “We’re years and years behind,” he said. “Other states are showing a lot more concern by taking an approach that considers not just one industry, but the whole ecosystem. We have a lot of catching up to do here in Louisiana.”

Limits sound reasonable and the industry can’t expect to be rein free. It is time regulations were imposed.