The Governor formed a climate change committee and they are releasing their suggestions and the first hits industry. In Louisiana 62% of our emissions come from industry, the most, by far, of all the states.

Louisiana industries could be charged major new taxes or fees based on their annual emissions of greenhouse gases, and be required to convince a panel of state agencies that they will comply with new emission reductions before getting permits for new or expanded facilities. Those are two of the major proposals included in a list of ways the state hopes to achieve “industrial decarbonization” — the removal of carbon dioxide and gases like methane and nitrogen oxide from emissions by heavy industry — as part of Gov. John Bel Edwards’ plan to reach “net zero” state carbon emissions by 2050. Reining in Louisiana’s large industrial sector will be perhaps the most important part of the plan: Industry was responsible for 62% of the 217 million tons of greenhouse gases released statewide in 2018, according to LSU professor David Dismukes.

nola.com

Union of Concerned Scientists

The Task Force has there work cut out. Coming up with the options was work but now selling them to industry will be real work.

The strategies being reviewed by Edwards’ Climate Initiatives Task Force are aimed at getting industrial facilities to do one of two things: reduce their existing carbon emissions to zero by changing their manufacturing processes, or capture and permanently store them so they don’t enter the atmosphere, or both. The task force expects the effort to be a double-edged sword for the state’s industrial sector, posing both financial risks and opportunities for the companies and their employees — and to the state’s economy — over the next 30 years as the U.S. seeks to avoid the worst effects of climate change. “We’ll need federal assistance equivalent to the effort to get a man on the moon,” Flozell Daniels, president of the Foundation for Louisiana and a member of the task force, said Friday. “It’s important to first recognize that we’re at a level of crisis that requires an extraordinary response.” Daniels said any federal subsidy would have to be designed to support the present level of employment while also meeting the carbon goals.

www.ussuca.org

The Governor is concerned about the effects of climate change, he is alone in the south east with this worry. He recognizes that with our outsized effect from industry they have to be changed the most.

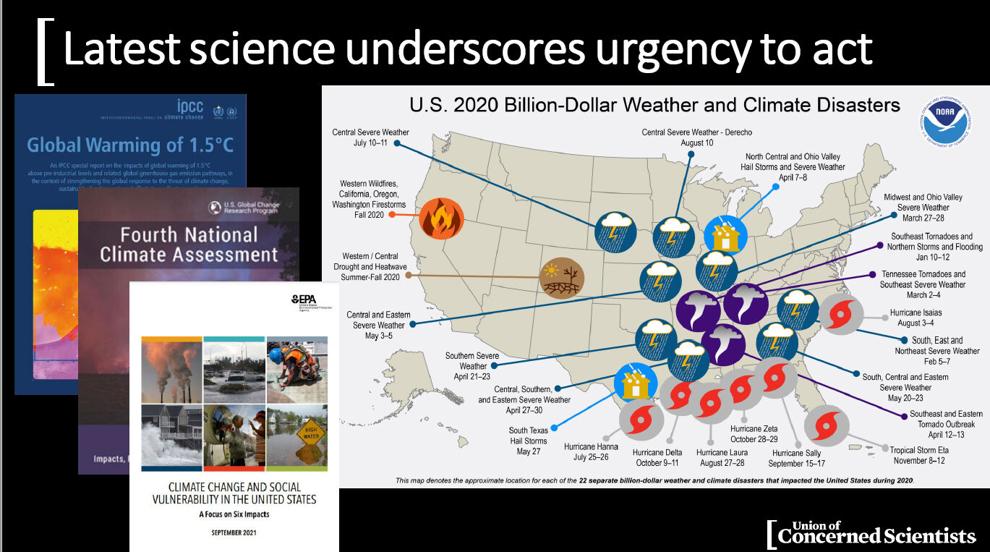

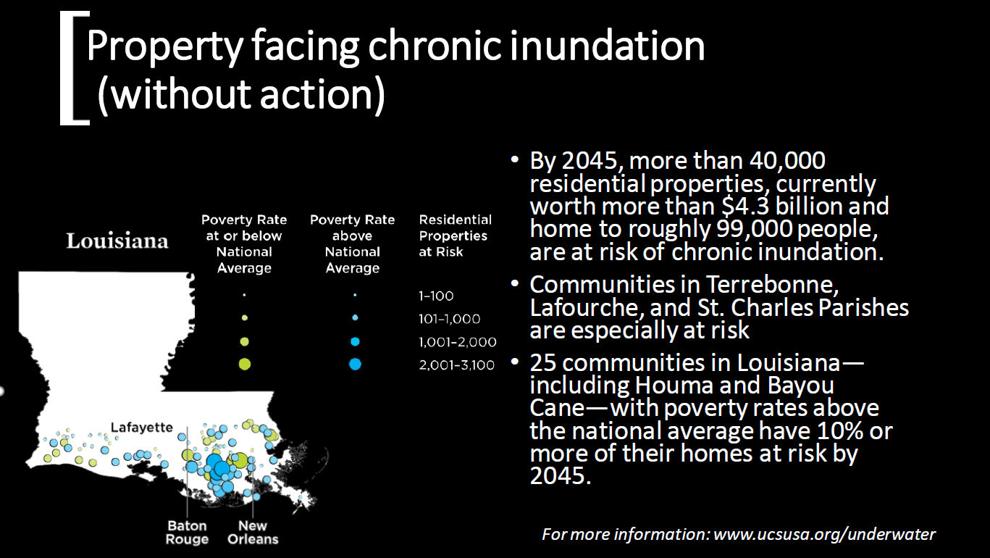

Edwards has said the state’s challenges include the threat of global-warming-fueled sea level rise destroying another 2,000 square miles of coastal wetlands; the increasing threat of damage from hurricanes and other weather events fueled by global warming; a variety of increased health risks from heat-related diseases; and the disruptions to the state’s economy that are likely to follow national efforts to reduce emissions that will result in switches from oil and gas produced in the state to non-carbon energy sources. Those threats were outlined Friday for the task force by Rachel Cleetus, director of the Union of Concerned Scientists climate and energy program. She pointed to the billions of dollars of damage caused by the 2020 and 2021 hurricanes and the 2016 Baton Rouge area rainfall flooding event, and her own organization’s recent report concluding that more than 40,000 residential properties in the state — worth more than $4.3 billion — will be at risk of chronic flooding by 2045. All of those can be linked to the multiple effects of global warming, she said.

www.ssir.org

This will not be a easy fix. It will involve more than just industry.

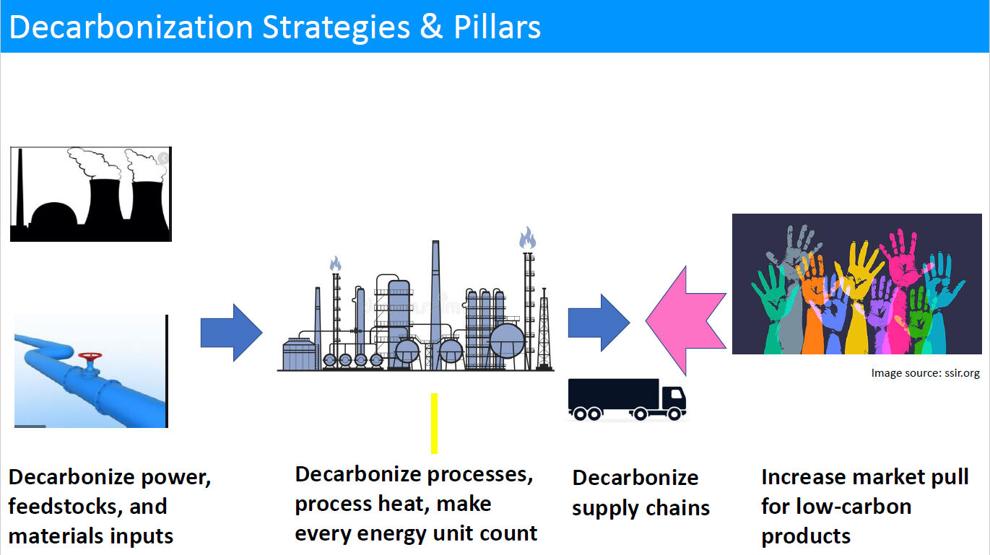

Ed Rightor, director of the Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s industrial program, told the task force that decarbonizing industry will require identifying how carbon is used in the manufacturing process, including as feedstocks, as heat sources, in chemically changing materials into products, and in operating all of the equipment necessary for daily operations. That review extends to how both raw materials and products are moved in the marketplace, and into efforts to entice the public to buy low-carbon products. In Louisiana, a small number of major emitters are responsible for an outsized share of the problem, according to Dismukes. In 2018, the top 20 carbon emitters were responsible for more than a quarter of the state’s emissions. Overall, Louisiana’s carbon emissions — industrial and otherwise — represented about 4.5% of the U.S. total that year. After industry, transportation — including trucks and vessels used by industry — is the next biggest emitter of carbon, representing 20% of the state’s 2018 emissions. That’s followed by the generation of electricity, mostly by utilities, at 13%, with some of that electricity also used by industry. According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, up to 15% of industry’s emissions could be cut through better energy management. Other steps likely will require major financial investments, including shifting from carbon-based fuels to low- or no-carbon electricity, the use of low-carbon fuels or of “distributed energy resources” — smaller, often modular sources of electricity including wind, solar or noncarbon fuel cells. In Louisiana, numerous industries, including oil refining and petrochemical and metals manufacturing, involve high-temperature processes that rely on high-carbon fuels, including coal, oil and natural gas.

Obviously Carbon is the major factor and there are a variety of reasons it is produced.

For some that use carbon fuels to create heat, electrification may be a substitute, with the source of electricity being itself a no- or low-carbon resource. Others may end up looking to “low-carbon” fuels, such as biofuels made from renewable resources, or no-carbon fuels like hydrogen. Decarbonization is likely to require industries to restructure their operations, as many facilities did after the 1987 establishment of the Toxics Release Inventory, which for the first time required industry to identify hazardous releases. In Louisiana, petrochemical facilities and refineries invested billions into new ways to reduce emissions. The carbon reduction efforts, if approved, will likely have the same multibillion-dollar redesign effect for existing facilities. They have already spurred the development of new technologies aimed at reducing, reusing or capturing carbon emissions, or the manufacture of new products that can store them. An example: Nucor Steel’s Sedalia, Missouri, manufacturing facility, which substituted wind-derived energy for natural gas in its manufacturing process. In Louisiana, Nucor’s iron manufacturing facility uses natural gas and is one of the state’s largest carbon dioxide emitters.

Photo from Ørsted

Cap and trade. This proposal has been talked about for many years and now it may be what is used here.

The tax and fee proposals being considered by the task force have been kicked around in various forms in Congress for years. One form, called “cap and trade,” would have federal or state governments set annual caps on the amount of total allowable emissions. Those emitting more than allowed under their permits would pay — or trade — for emissions reductions accomplished by other facilities, with releases being reduced each year until the state reaches its zero goal. Cap-and-trade programs for sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions that produce acid rain have been successfully used nationally since 1990, and are credited with reducing damage to Appalachian forests. A direct tax on emissions — called “carbon pricing” — would have the same goal, with the cost passed on to customers, but with the revenue redistributed by either the federal government or states. Some tax plans would allow part of the revenue to be returned to industries to pay for carbon reduction or sequestration projects, while others would distribute the money to low- and moderate-income residents to offset increased prices on products.

(Google Earth) Google Earth

Industry seems to be on board for this way of fighting climate change.

Both the Louisiana Chemical Association and ExxonMobil recommended carbon pricing be included among the state’s strategies. “Putting a price on carbon helps to incorporate climate risks into the cost of doing business,” said Tokesha Collins-Wright, vice president for environmental affairs with the chemical association, which represents most of the state’s larger manufacturing facilities. “Carbon pricing gives an economic signal and allows emitters to decide whether to continue their activities and pay for them or to reduce their emissions by seeking technologies and products that generate less of it. In this way, the market is operating as an efficient means to cut emissions, helping foster a shift to a clean energy economy and driving innovation in low- or lower-carbon technologies.”

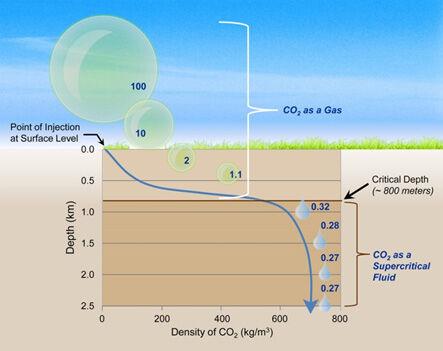

The proposed strategy also included a number of recommendations to support a strategy of injecting carbon dioxide captured during manufacturing into deep underground rock formations across the state, a process called “Carbon Capture, Use and Sequestration,” or CCUS. The energy industry has used a form of this strategy for years to increase production of oil in old, marginal reservoirs, injecting the gas into the reservoir to push oil to the surface.

U.S. Department of Energy

Sequestration also has industry supporters.

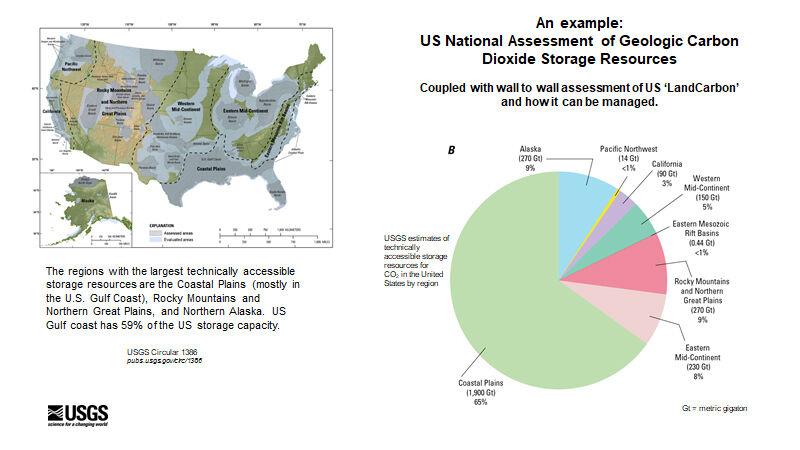

Supporters of sequestration include a number of industry members on both the task force and its advisory committees, including representatives of the chemical association and the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil & Gas Association. A key supporter is Gray Stream, CEO of Gulf Coast Sequestration LLC, which is attempting to get a sequestration project approved in Calcasieu Parish. Stream is calling for the development of a series of sequestration hubs across the state, connected to locations where carbon dioxide is collected by new regional networks of pipelines. Stream said one reason the sequestration process isn’t yet trusted is that only six such projects have been permitted in the U.S. “The lack of permits creates a public perception that carbon capture and storage is not a viable option for permanent CO(2) reduction,” Stream said in his proposal. In April, the state Department of Natural Resources asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to give it authority to administer the federal regulations governing carbon sequestration. The agency already has the authority to oversee underground injection of other hazardous liquid waste streams. Louisiana would be the third state to receive such approval. North Dakota and Wyoming already have been granted the authority. While the EPA approval process normally takes about five years, the state has asked for expedited approval. The DNR’s Minerals Board already has begun negotiations with at least two companies that would allow sequestration wells under state-owned parks and wildlife refuges. On Oct. 4, the board approved an agreement with Capio Sequestration that would allow the company to make use of formations beneath 44,511 acres in parks in Ascension, Iberville, Pointe Coupee, St. John the Baptist, St. Martin and St. Landry parishes. Capio is a sister company of Gron Fuels, which received permits earlier this year for a $9.2 billion renewable diesel refinery at the Port of Baton Rouge. In 2020, the company said it planned on using underground carbon storage to handle carbon emissions from a biomass-fueled power plant and from its manufacture of diesel from a variety of vegetable and waste vegetable oils. The diesel also would produce only 20% of the carbon emissions of diesel manufactured with crude oil, the company said. The Minerals Board also considered a similar request by Air Products Blue Energy, to use state land beneath parks and refuges in Livingston, St. James, St. John, Cameron and Tangipahoa parishes.

U.S. Geological Survey

Sequestration also has its detractors.

Several national and state environmental groups are wary of the carbon sequestration process, warning that sites being considered for sequestration are often in areas where people of color, indigenous residents and the poor already are dealing with health issues related to other industrial emissions. Adam Peltz and Scott Anderson of the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund pointed out that the DNR’s application to take over the EPA regulations did not require that construction of pipelines serving sequestration sites be subject to environmental justice guarantees, and they recommended adding such requirements.

The Governor realizes that if you regulate industry you need their buy-in so he looked for ways that they support. He is a pragmatist in that he achieves what he wants willingly by involving those impacted.