(NASA)

Too many nutrients flo into the Gulf from too many sources. A dead zone develops and we have one close to shore.

The Gulf of Mexico’s “dead zone” is again expected to be larger than the state of Connecticut this summer, NOAA said Thursday in its prediction of the low-oxygen area where bottom-living organisms will die and fish and shrimp will attempt to avoid. The dead zone, the result of nutrient pollution carried down the Mississippi River, is expected to cover a near-average 5,364 square miles of bottom waters off the coasts of Louisiana and Texas at the end of July, and some researchers warn it could grow to 6,500 square miles by August. While this year’s low-oxygen area is expected to be slightly smaller than 2021’s and less than a five-year average, it’s still three times greater than what officials hope to achieve by 2035. A federal-state hypoxia reduction task force wants to see the dead zone reduced to just 1,900 square miles by that time. In 2001, the task force called for that goal to be met by 2015. But when it became clear that efforts to get Midwest farmers to reduce their use of key fertilizers was not working, the task force in 2016 pushed the goal date back to 2035. It also added a new goal to reduce the dead zone’s size by 20% by 2025, which is just three years away.

nola.com

Hypoxia is something that we alone do not produce but the farms and industry up the Mississippi all contribute to what we see here.

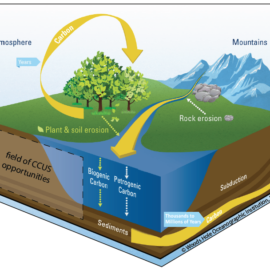

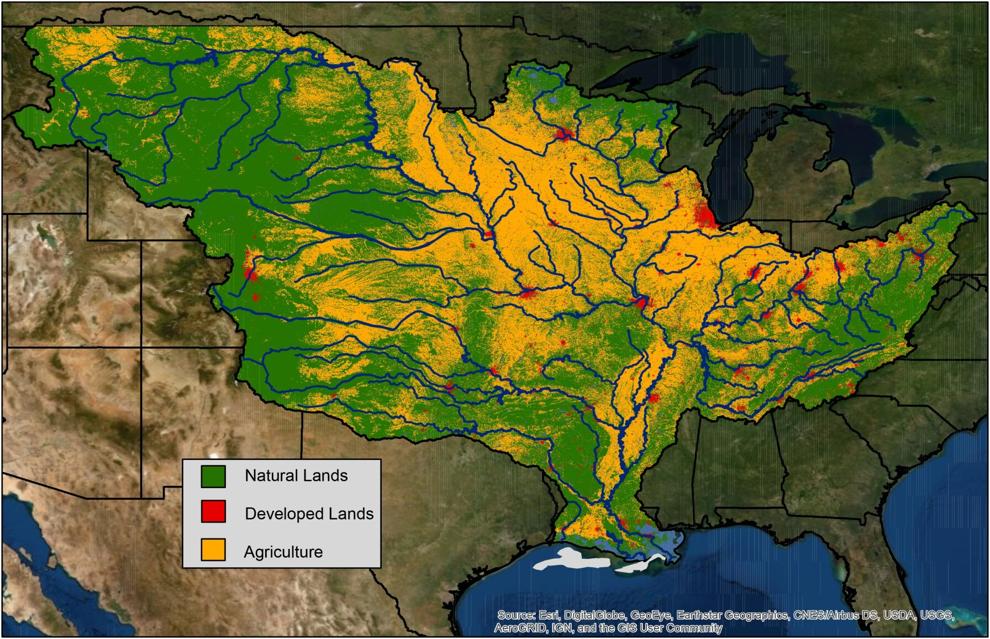

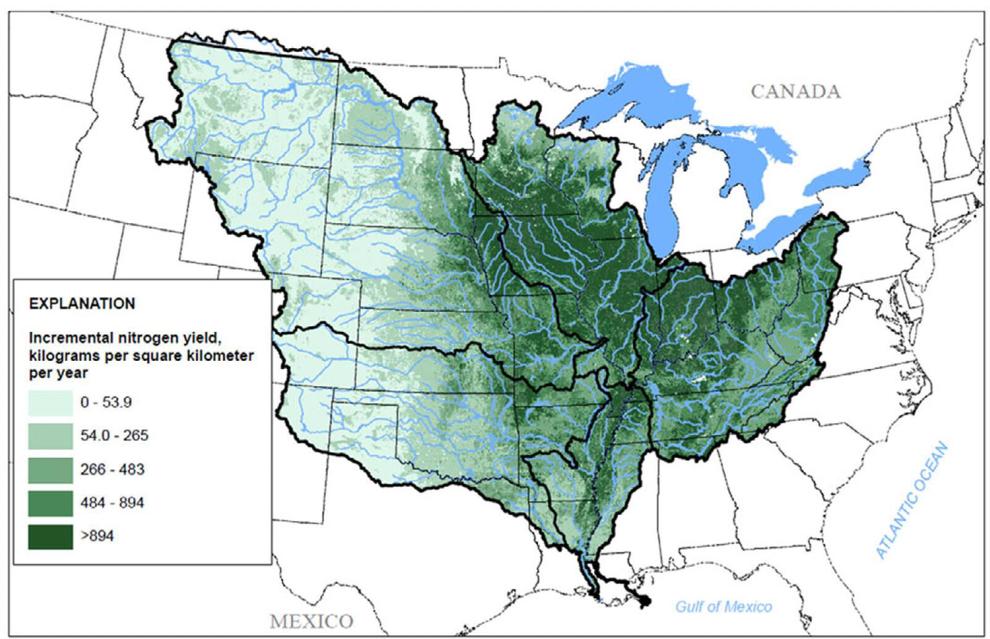

The formation of hypoxia, the scientific term for water containing less than 2 parts per million of oxygen, is linked to the flow of two key nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus, that are carried from farms, septic tanks and sewage treatment plants in the the Mississippi River watershed by melting snow and springtime rainfall to the Gulf. The river’s fresh water creates a layer over saltier Gulf water where blooms of algae grow and then die, sinking to the bottom and decomposing, using up oxygen. The low-oxygen conditions generally last until tropical storms or other weather events disrupt the layer of fresh water, mixing air from the surface into the saltwater on the bottom. The U.S. Geological Survey measures nutrients throughout the Mississippi and Atchafalaya river basins throughout the spring. Teams of scientists at Louisiana State University and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, the University of Michigan, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, North Carolina State University and Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, plug that information into computer models and use other strategies to estimate how large the dead zone will be at the end of July. At that time, a team of LUMCON scientists will conduct an underwater survey to determine how low oxygen levels are across the coast. Levels of nitrate, largely from nitrogen-based agricultural fertilizers, have remained steady in the river since 1985, according to USGS monitoring data, and it’s the nitrate that’s been found to be the bigger source for the algae blooms in the Gulf, compared to phosphorus, scientists say.

(NOAA)

Large sums of money have been spent to cut down on the out flow of the farms and other sources to little effect.

During that same time, literally hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on a variety of efforts to reduce nutrient runoff from agriculture in the river’s watershed. They have included returning marginal farmland to use as wetlands and the planting of grassy strips around the edges of farmland to capture nutrients, as well as training farmers to use “precision agriculture” techniques using satellite global positioning systems to limit the amount of fertilizer used on crops. But those efforts have done little to reduce the size of the annual summer dead zone, with most low measurement years linked to the passage of storm systems, including hurricanes, over the coast that mixed oxygen back into bottom waters. “No reductions in the nitrate loading from the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico have occurred in the last few decades, the interval since the formulation of the Hypoxia Action Plan environmental goal,” said LSU researchers Eugene Turner and Nancy Rabalais, in their estimate report. “No matter what people say they are doing in the watershed, it is either not enough or not the right stuff,” agreed Don Scavia, a researcher leading the University of Michigan’s hypoxia research team. “It has now been more than 20 years since the action plan, so it is hard to blame slow environmental response times.”

(Dale Robertson and David Saad, USGS, Journal of the American Water Resources Association)

The EPA is working to change this and to help cut down the out flow.

In one effort to change that, EPA is investing $60 million from the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law over the next five years to enable the hypoxia task force to scale up state nutrient reduction strategies under what is known as the Gulf Hypoxia Action Plan. EPA expects to award the first round of grants to states, said an EPA statement. Doug Daigle, coordinator of the Louisiana Hypoxia Working Group, said Louisiana has also spent $9.5 million from the natural resource damage assessment of the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill on wetland conservation projects aimed at nutrient reduction. The Louisiana BP Trustee Implementation Group has another $10.5 million available for other projects. Mississippi’s trustee group also has about $27 million available for nutrient reduction strategies from the BP natural resource settlement, he said. But Scavia doubts those efforts will have much of an impact, especially since EPA has repeatedly decided against more aggressive regulatory efforts aimed at requiring agricultural operations to reduce emissions by specific levels along numerous segments of streambeds in the Mississippi watershed. The agency has successfully turned back legal challenges in federal courts by environmental groups, including the New Orleans-based Healthy Gulf, to set such limits. “The mention of $60 million of new actions is pretty laughable when compared to the billions being spent each year on the farm bill,” he said, referring to federal legislation on agriculture. “It is clear that USDA programs are not enough and with EPA’s inability (or reluctance) to regulate the agricultural industry like other industries, there is little hope this problem will ever be solved. As I mentioned in our own press release, it is clear that the federal and state agencies and the Congress continue to prioritize industrial agriculture over water quality.”

Not much we can do about this but on the other hand, maybe this will help the menhaden as it forces the fishermen to go farther off shore.