August with no named storms. Unusual to say the least but we still need to keep our guard up and not “get shipwrecked”.

The month of August has ended with no named tropical storms in the Atlantic for only the third time since 1950. But while the quiet season so far has been unexpected, weather experts warn it’s not time to let your guard down. “It is important to remember the lessons of Hurricane Andrew, which devastated south Florida and Louisiana in an otherwise quiet year,” said Jamie Rhome, acting director of the National Hurricane Center. Andrew, the first named storm of the 1992 season, made landfall on Aug. 24 in Homestead, Florida, as a catastrophic Category 5 hurricane, with sustained winds of 165 mph. On Aug. 26, Andrew made a second landfall at Point Chevreuil, just south of Franklin, as a Category 3 hurricane, with sustained winds of 115 mph, causing $1 billion in damage in the state. “It only takes one landfalling hurricane to make it a bad season for you, and we still have many months to go in hurricane season,” Rhome said. “We don’t want people to lower their guard, as one storm could be enough to make up a season.”

nola.com

THis is the current picture and while the track says we should be clear the movement of the storms can vary a lot.

The recent quiet period has been the longest without a named storm in the midst of a season since 1941, when there were none reaching tropical storm strength until Sept. 11. And it’s the third time there have been none of tropical storm strength in August since 1950, according to the National Hurricane Center. Colorado State University Climatologist Philip Klotzbach said the other two years without August named storms were 1961 and 1997. “1997 ended up a below-average season, while 1961 had an extremely active September and ended up a hyperactive season,” Klotzbach said, with 14 tropical depressions, a dozen tropical storms and eight hurricanes, including five major hurricanes of Category 3 or stronger. And both Klotzbach and NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center warn that the early-season forecasts of a more active than normal hurricane season have plenty of time to play out. “I expect we’ll get 1-3 named storms in the next 3-4 days,” Klotzbach said, pointing to the National Hurricane Center’s tropical forecasts on Tuesday, which predicted two systems in the central Atlantic had an 80% chance and one system in the eastern Atlantic had a 50% chance of developing into a tropical depression or storm over the next five days.

Keep prepared.

“Please tell people not to let their guard down,” said NOAA’s Matthew Rosencrans, who oversees the agency’s seasonal forecasts. “2020 was the busiest season in 100 years, and 2021 was the third-busiest. “This may seem to be a very inactive season but we are still two weeks before the peak of the hurricane season,” he said, which is Sept. 10. “People should consider this just a little bit longer time to prepare for what’s coming.” The storm lull has been welcome in Louisiana, which was hammered by Category 4 Laura and Category 2 Delta in 2020, and by Category 4 Ida last year, with thousands of businesses and homeowners still struggling to rebuild damaged roofs and interiors. Well over 10,000 residents are still in temporary trailers provided by FEMA or the state.

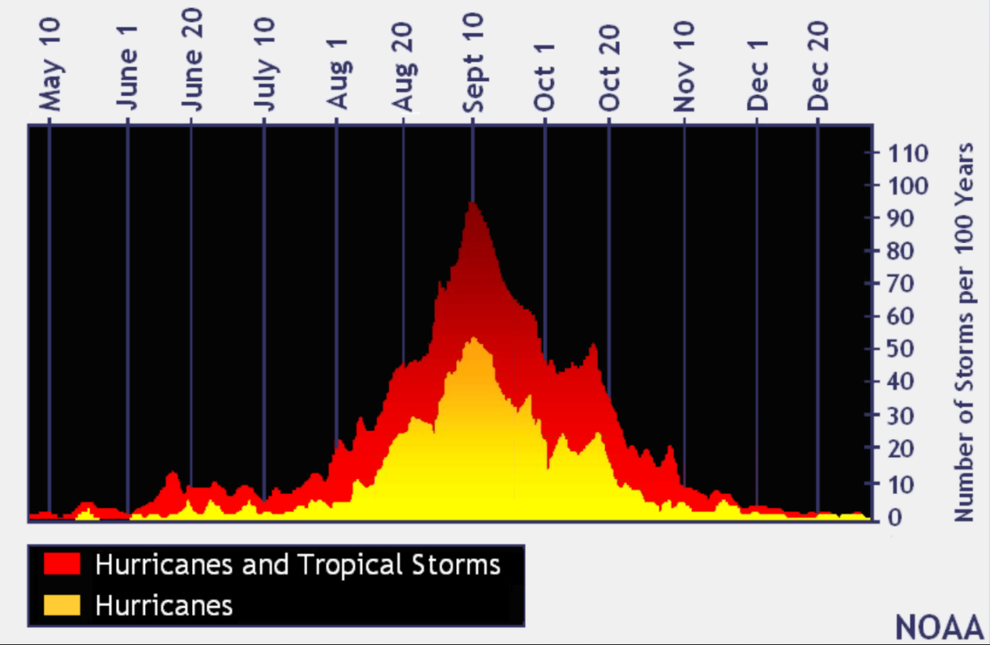

(NOAA)

Why have we had this lull?

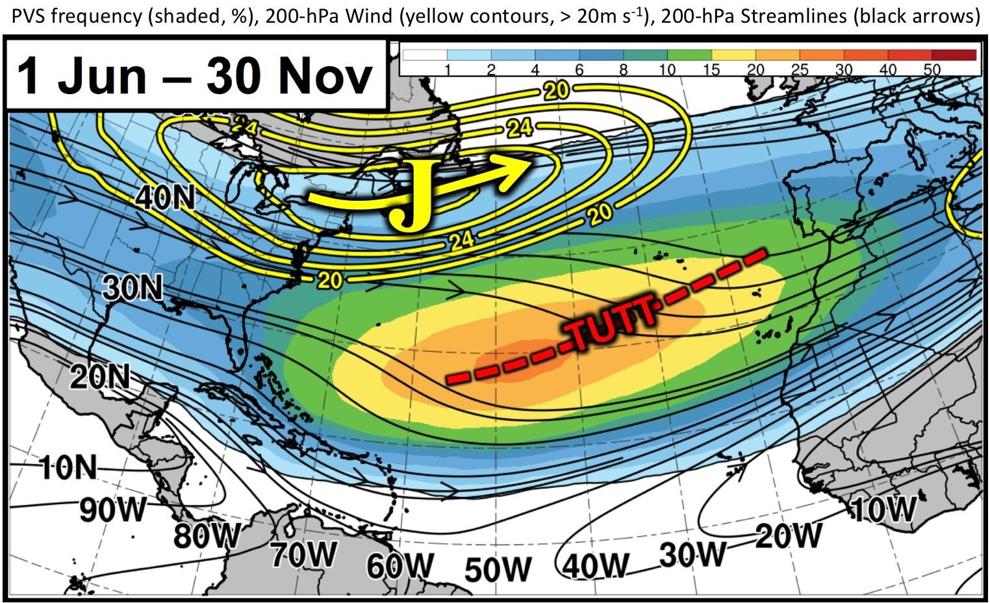

Klotzbach and Rosencrans say an unusual set of factors are likely responsible for the zero-storm August. The most significant is likely the stronger than normal wind shear that was present in the first half of the month, which tends to disrupt the ability of batches of thunderstorms to gather into a tropical system. The likely cause has been what forecasters call TUTT, which stands for tropical upper-tropospheric trough, an upper level trough of low pressure that was stronger than normally seen during active seasons, Klotzbach said. The TUTT condition might have been linked to an unusual difference in sea surface temperatures in the tropical and more northerly subtropical areas of the Atlantic. The differing temperatures that caused in the atmosphere may have triggered the formation of more frontal systems that created the wind shear.

(NOAA)

The Pacific has had lower temperatures.

Rosencrans said another factor may be how the third year of continued lower than normal sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, known as La Nina, acted this year. In most years where La Nina in the Pacific results in reduced wind shear in the Atlantic, the cooler Pacific water is found closer to the North American West Coast. This year, the coolest temperatures recently moved farther west, in the central Pacific, he said. Drier air in the central Atlantic Ocean also limited the ability of tropical waves moving west out of Africa to form the thunderstorms necessary to trigger tropical system formation, Rosencrans said. Another factor tamping down storm formation has been a greater than normal number of Saharan Air Layer outbreaks this year, including some in early August, said Jason Dunion, a researcher with NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division. The layer includes extremely dry air, sand and dust from the Saharan desert, and the dry air disrupts the formation of thunderstorms. Klotzbach pointed out that global forecast modeling indicates the wind shear pendulum seems to be shifting back to less shear, meaning potentially more storms. It has already dropped off across the tropical Atlantic during the past two weeks, and is expected to remain depressed for the remainder of the year. “It’s almost eerie, like waiting for some explosion of storms to happen,” Louisiana State Climatologist Barry Keim said of the August lull. “We’ve passed this ominous date, Aug. 29, the anniversary of Hurricanes Katrina, Isaac and Ida, which all made landfall on that day.”

There are some worrying signs which means the worst may not be over.

But Keim also is watching the National Hurricane Center’s forecasts and remaining concerned. “I think we’re gonna be popping off some named storms pretty soon. We’re already in the heart of the season, but we’re getting close now to the midpoint of the season, and that’s kind of the point where we get the maximum sea surface temperatures across the breeding grounds,” he said. In the last 100 years, the tropics have been the most active in August, September and October, with Sept. 10 being the peak of the season, according to federal forecasters. About 80% of the systems that have hit the Gulf Coast formed during this time, according to the National Weather Service in Slidell. Rosencrans said it remains problematical to predict where landfalls will occur in the United States during the remainder of the season. That’s the job for the National Hurricane Center’s shorter forecasts, he said.

In the Caribbean the water is warm.

However, it’s clear that conditions remain favorable throughout the Caribbean and stretching into the Gulf of Mexico for tropical cyclone intensification because of very warm sea surface temperatures. That includes the location of the “loop current” of much deeper warm water in the central Gulf just off Louisiana. The loop current is part of the warm, deep Gulf Stream that breaks off and floats in the Gulf. When a storm passes over it, “rapid intensification,” where wind speeds can jump one or two categories in just a few hours, is possible. So far this year, there have been three named storms: Alex, Bonnie and Colin, and an unnamed system that the center issued forecasts for, though it never gained a name before making landfall on the Texas-Mexico border . And while hurricane season officially ends on Nov. 30, storms can form at any time. “There is still a tremendous amount of recovery work ongoing in Louisiana after hurricanes, Laura, Delta, Zeta and Ida impacted Louisiana along with many other smaller weather related emergencies,” said Casey Tingle, head of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness. “While we are thankful for a break in tropical activity for the start of the 2022 season, there are no guarantees that will continue.”

It sounds like just keep them out of the Caribbean and we will be OK.