Livingston is a selected site for carbon capture but they are balking. Too many other disasters have been there and would this be another?

Livingston Parish council member Tracy Girlinghouse grew up about a mile away from what was once the site of Combustion, Inc. in the Walker area. Operating largely as a used oil reclamation facility from the 1960s to 80s, the company became infamous when a class action lawsuit alleged it put residents health at risk by improperly disposed of huge amounts of hazardous chemicals; it became a federally designated “Superfund site” for the cleanup of hazardous waste. Girlinghouse remembers a childhood spent swimming in West Colyell Creek nearby — where toxic chemicals may have drained. “I don’t know what that’s going to do to me, what it has done to me, what it’s going to do to me later on,” he said of his time spent at the creek.“Everything doesn’t hurt you until it hurts you.” Girlinghouse recalled those memories in a recent council meeting as members considered passing a moratorium on carbon capture injection wells. Residents of that parish, like several others in the region, are trying to stop an influx of carbon capture projects slated for the area, such as two planned sites in Holden and Lake Maurepas.

nola.com

Gun shy but for good reasons and it sometimes looks like the tail is wagging the dog on many of these projects.

Opponents frequently invoke the legacy of disastrous hazardous waste disposal in the parish and worry that history will repeat itself. The next potential catastrophe might not happen immediately, they say, but the parish has been burned — both figuratively and literally — by industrial accidents in the last 40 years. Company leaders for the projects have said their carbon capture technology is proven, safe and effective, but so far Livingston residents appear unconvinced. Council chairman Jeff Ard echoed his constituents’ sentiments before the final vote that halted carbon capture for at least a year in the parish. “I, for one, am tired of Livingston Parish being everybody else’s dumping ground. I’m tired of it,” he said. “We’ve got the dump. We’ve had CECOS. It’s time for us to stand up and say we don’t want your trash anymore. And if you’re going to force it down our throats, you’re going to pay us to bring it here.”

What are the right questions? Were they asked? Who defines safety?

CECOS Intenational cropped up several times in public meetings in recent weeks as residents questioned the safety of carbon sequestration and the potential impact it could have on their communities. When that company came to town, residents were told a similar tale of safety, said Albany Mayor Eileen Bates-McCarroll, who invoked CECOS in public remarks regarding the future of the parish’s water wells. “We were told what a wonderful, safe project this was going to be,” she said of CECOS. “We now have a national waste hazard in our community that should have never been there. The right questions weren’t asked. There weren’t enough studies, because I’m sure if they did they would have never been permitted.” The CECOS hazardous waste facility, located near the Interstate 12 interchange at Livingston, was the source of repeated complaints during its 13 years of operation before the state ordered it to close. The EPA found “more than 1,700 violations of the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act” between November 1980 and January 1986, according a report in The Morning Advocate from the time. Violations at the site included “land-filling of ignitable waste and hazardous waste containing liquids, failure to properly analyze hazardous waste and unauthorized waste piles,” the article says. Notably, contaminants from the site were discovered “as much as 70 feet below the site and within 30 to 35 feet of major aquifers that supply drinking water to people in the Livingston area,” the report continues. Expert witnesses in a costly class-action lawsuit agreed that the materials handled at the site “were capable of aggravating pre-existing respiratory problems and causing upper respiratory distress, including dizziness, coughing, runny eyes, nasal congestion and nausea.” The lawsuit was filed in 1987, and in 2011 parties reached a $29.5 million settlement.

There was also an oil and waste reclamation site.

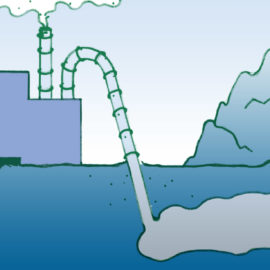

Residents also have concerns that the sequestered carbon will jeopardize homes near the sites — and possibly ruin Lake Maurepas as a sanctuary for fishermen and boaters. Girlinghouse said he knows he was in the danger zone near Combustion, Inc. But to this day he doesn’t know how that may have impacted his life. Combsution, Inc. oil reclamation and wastewater treatment facility in the Walker area collected oil waste sent by a pipeline from the company’s nearby petroleum hydrocarbon recycling plant. From the late 1960s until the early ’80s, the site accumulated about 3 million gallons of sludge, oil and waste water in earthen pits that contaminated soil and groundwater. In 1996, a “government assessment found people in the area were exposed to chemicals through the air, skin absorption, the soil and smoke from three on-site fires” and suffered from “sinus trouble, hoarseness and rashes,” among other maladies, according to an article at the time. Researchers had profiled 211 people in 62 households in the area. Nineteen of the 62 homes had more than one incident of cancer, the article says. In that class-action lawsuit, Combustion Inc. settled for $131 million; $4.5 million went to building the Livingston Literacy and Technology Center, which opened in 2007. The Superfund site where Combustion, Inc. once stood resulted in a $12 million cleanup effort.

Also add to the list the train derailment.

As the fight over carbon capture has played out over the last month, residents have repeatedly and fearfully referenced a relatively recent disaster involving the technology in Satartia, Mississippi. In 2020, a pipeline carrying compressed carbon dioxide ruptured. Over 40 people required hospital treatment and more than 300 were forced to evacuate. It remains a crucial concern of area residents: How can companies ensure the safety of CO2 during transport over long distances? In the town of Livingston, some residents may well remember a different kind of crisis involving critical materials transport that scarred the land for decades. On Sept. 28, 1982, around 5:12 a.m., an Illinois Central Gulf freight train staffed by a crew that had been drinking ran off the tracks just north of Livingston Town Hall. Of the 43 cars that derailed, 34 contained hazardous materials or flammable petroleum products. Many were breached, then burned and exploded, releasing toxic vapors and smoke across the town. As the tanker cars went up in smoke, some first responders couldn’t decipher the chemical warning symbols in the blaze, so they didn’t know which fires to douse with water, what to spray with foam and what to let burn out. Miraculously, no one died in the disaster. About 3,000 people in a five-mile radius were evacuated from their homes, some for weeks. Nineteen residences and other buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged. All told, more than 200,000 gallons of toxic chemical product spilled and leached into the ground. Short-term emergency clean-up gave way to messy and inevitable lawsuits. Rebuilding followed, along with years of health monitoring. It wasn’t until 2015 — more than three decades since the derailment — that wells were plugged and the monitoring station began to shut down.

In every case, there was promised safety. They lied.

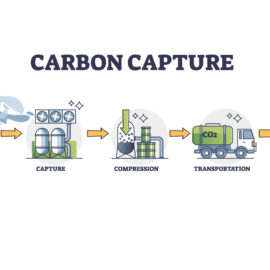

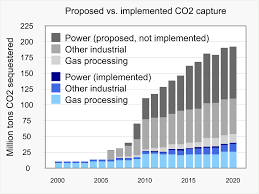

Representatives for Air Products, the company that plans to store CO2 below Lake Maurepas, and Oxy Low Carbon Ventures, a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum, whose project will store pressurized carbon near Holden, have said in public meetings their technology is safe and proven, and that their companies have good track records. At a special parish council meeting to discuss the projects, company leaders presented powerpoint presentations showing how the technology works, why they chose Louisiana for sequestration and the safeguards they will have in place to protect the surrounding community. “Carbon sequestration is permanent, proven and an environmentally sound disposition of CO2,” said Nile Bolan with Air Products at that meeting. Brian Landry, vice president of political affairs at the Louisiana Chemical Association, has also defended carbon capture to the Livingston audience on more than one occasion. “The permits required for these projects are the strictest in the United States and constant monitoring is required,” he said at a recent council meeting. But talk of safety, and even the economic benefits the projects could bring to the parish, have not swayed council members or many constituents. After discussing his childhood spent near a hazardous waste site, Girlinghouse said there was unlikely to be a sum of money he would trade for peace of mind. “Ascension has a lot of industry. They have a lot more revenue, a lot more money to do things with,” he said. “I say, good for them. Because I wouldn’t want those plants of [that] magnitude in my backyard.”

Maybe, just maybe, people are tired of being a dump site or having polluted air.