With some backlash, the Port of New Orleans says it needs the terminal at Violet and has made some changes.

The Port of New Orleans on Thursday announced modifications to its plan to build a $1.5 billion container ship terminal on the Mississippi River at Violet, with the aim of appeasing St. Bernard Parish residents, some of whom still oppose the project. The changes come as Port Nola ends a two-year period of consultation with local residents and agencies, and enters a phase to obtain government permits so it can find public and private financing and start construction. The modifications were made to win over St. Bernard residents some two years after Port Nola bought 1,100 acres in St. Bernard and settled on the site for the project, called the Louisiana International Terminal. If it is approved and funded, Port Nola wants to start major construction in 2025 and have it ready to take its first big ship in 2028.

nola.com

Courtesy Port of New Orleans

Houston and Mobile are competitors and we need to gain a firm portion of the trade we are now losing to them.

Port CEO Brandy Christian and Michael Hecht, the CEO of regional economic development agency GNO Inc., reiterated their case that the container port is needed for New Orleans to make up ground lost to other Gulf South ports, including Houston and Mobile, Alabama. Though Port Nola’s upriver container terminal at Napoleon Avenue has recently taken delivery of four huge new gantry cranes to increase its handling capacity, container ships are growing in size and those above 10,000 20-foot equivalent units cannot make it under the Crescent City Connection to reach Napoleon Avenue. “If Louisiana does not quickly become ‘big-ship ready,’ we stand to lose to competing ports,” Christian said.

Politics has delayed the decision despite the urging of the port.

Port officials have been arguing during their campaign to win support for the Violet terminal that there is a huge opportunity for New Orleans, but that the region has been losing to competitors because of political dithering. The container shipping market for the U.S. as a whole has been growing at around 3% annually over the last decade, but it has been growing at twice that rate for Gulf Coast ports. That’s largely because mega-ports on the east and west coasts have become jammed with ships, creating long delays that have prompted big importers to look for alternatives. But while New Orleans has seen container volume grow more than the national average, it is lagging well behind Gulf Coast rivals. Particularly worrying, said Rives, has been the huge growth — over 320% over the past five years — in container volume coming through the port of Mobile. She also pointed a study the port commissioned from an economic consultant who concluded that Louisiana would lose 10,000 jobs, $10 billion in economic output and $200 million in tax revenue over a decade if it failed to build a new deepwater container terminal. “One of the benefits of building a new terminal from the ground up is that we can implement the latest advances in green technologies,” Christian said. This will include an electricity sub-station that Port Nola is building with Entergy, so docked ships could use the local power supply instead of running their diesel engines, a major source of pollution at busy ports.

Roads are the main concern as Violet is on a 2-way road and that continues into St Bernard.

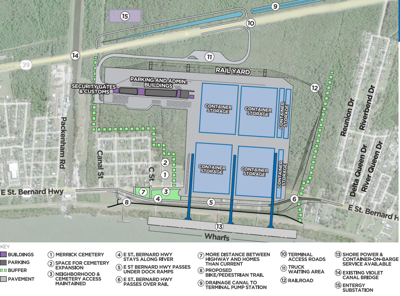

A major objection raised by residents was also the likelihood that as the port ramps up, port-related truck traffic would choke roads in St. Bernard. Thus the port’s new plan says the terminal will be designed to grow container-on-barge services, which move containers up and down the river by barge rather than road or rail. Christian acknowledged, however, that the current low level of the Mississippi — as well as the high level in 2019 — shows the limitations of a river traffic strategy. While the river at New Orleans is still deep enough to accommodate big ships and barge traffic, the low level has restricted barge movement upriver, from Baton Rouge to Memphis, Tennessee, and beyond. Christian said the Louisiana Legislature recently committed to $50 million for construction of an elevated highway in lower St. Bernard and released $2 million for the Regional Planning Commission to conduct a feasibility study. The “St. Bernard Transportation Corridor” would connect lower St. Bernard to the interstate highway system. Port Nola is competing with others around the country for federal infrastructure money for the highway project. The new design also keeps the highway along the river rather than re-routing it around the port, which was a major source of locals’ resistance. Port Nola has also included more green area “buffers” between the shipping terminal and neighborhoods, an overpass for cars to avoid a railroad crossing, space for Merrick Cemetery to expand and room for a biking and walking path to be built by the parish along the levee.

The port has support from industry and the Parish but there is oppostion.

The port released a statement that included support from Kevin Gabriel, president of the St. Bernard NAACP, and from Mindy Nuñez Airhart, CEO of Southern Services and Equipment, a steel products maker, who is a St. Bernard Chamber of Commerce board member, and chair of the New Orleans Chamber of Commerce. But the main opponents of to the Louisiana International Terminal, who have grouped under the Save Our St. Bernard banner, were not swayed. “This is nothing more than a public relations stunt that their $4 million consultants have come up with to deceive the public,” said Robby Showalter, a shipping executive and St. Bernard resident who leads Save Our St. Bernard. “They still have not addressed the four major items of concern for the residents of St. Bernard, along with the 10,000 people who have joined SOS in opposing this project.” He reiterated that some experts have said a container port would be much better located at least 30 miles downriver in deeper water. And he said the proposed feasibility study for a new transportation corridor does not assure any road building before Port Nola would start constructing the shipping terminal. He said residents are still deeply worried about the pollution and destruction of natural habitat from building a huge terminal in the middle of their neighborhoods.

There is a pending law suit.

There is still a pending lawsuit brought by some residents. Lawyer Sidney Torres III, who filed the lawsuit in December, said all five local judges have recused themselves from the case, and an outside judge recused himself because his son has done work for Port Nola. The case is awaiting the Louisiana Supreme Court appointing a judge from elsewhere in the state. Christian and Hecht said the economic case for the terminal at Violet is overwhelming: 17,000 new jobs and $1 billion of new tax revenue, including $470 million to St. Bernard Parish. New Orleans has many natural advantages, including the river, all the major railways and interstate highway access, but has become complacent while rival ports have invested, they said. “We must invest like our Southern state neighbors or get left behind,” Christian said. “If we do it right, we have the opportunity to be the next generation leader in global trade.”

Economically I can see the need for a port but where? I am not sure Violet is the right place but 30 miles down the river and our losing land how viable is that.