For those who love hurricanes this was a bad season. For most of us it was a good one.

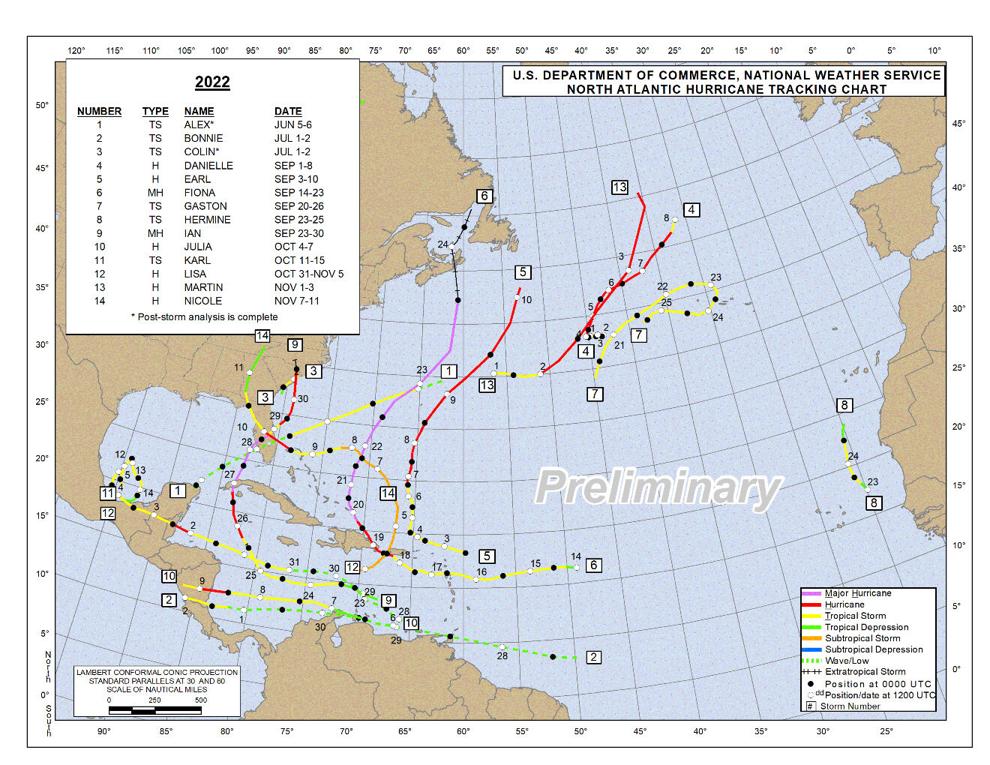

This year’s hurricane season delivered something Louisiana hasn’t had much of recently: quiet. The Atlantic Basin season that began June 1 and ends Wednesday included a near-average number of tropical storms and hurricanes, but also a greatly needed pause in landfalls along the Louisiana coastline, providing residents with more time to recover from the last two disastrously intense years. The season ends with 14 named storms (tropical weather systems with winds of 39 mph or greater), including eight that became hurricanes (with winds of 74 mph or greater) and two of those that became major hurricanes (with winds of 111 mph or greater). An average season has 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes. For Louisiana, this year’s break in storm activity allowed the Governor’s Office for Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness to catch up on assisting parishes with recovery efforts dating to Hurricane Rita in 2005, said director Casey Tingle. “Having a quiet hurricane season for us has certainly been helpful to get that work accomplished,” he said. It’s also provided time for the agency to review its role in assisting parishes and cities with evacuation decision-making, as well as ways to speed and track the delivery of emergency resources to local governments and expand its search for additional emergency shelter capacity for future disasters, Tingle said.

nola.com

The lack of storms also let the state go to help other states who were not so lucky.

The pause also allowed Louisiana to lend assistance to other states during natural disasters, said GOHSEP press secretary Mike Steele, including sending staffers to New Mexico during wildfires, and providing assistance to Florida officials after Hurricane Ian. The state also has used the downtime to help sort out issues with the provision of recreational vehicles to residents with damage in past storms. “For our Ida recovery, we had a big state emergency shelter program that allowed us to use RV trailers in a lot of the largest impact areas,” Steele said. “Because it was a new program, there were a lot of transition points, where families were moving out, where they transitioned into direct housing provided by FEMA. “We’re also working out long-term plans to deal with the trailers themselves,” he said. “Hundreds are scheduled for delivery to Florida, and some to Kentucky, where severe flooding occurred earlier this year. And others will be auctioned off at some point.” Steele said the lack of storms also helped the agency by not disrupting a variety of training programs aimed at assisting local parishes to deal with emergency events.

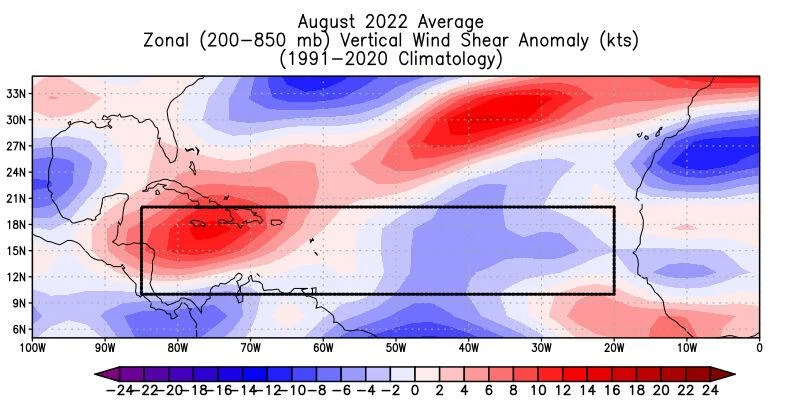

This graphic shows where greater or lesser than normal wind shear occurred in August. Note that high amounts occurred in the box outlining where many tropical cyclones form, including portions of the Caribbean Ocean.

(Colorado State University)

The main question was why were we sparred?

Louisiana was protected in 2022 largely by frontal systems passing across the United States that dragged the few storms able to make it into the Gulf of Mexico to the east. During the middle and late months of the season, similar frontal systems in the Caribbean pushed the storms west into Central America or Mexico before they could enter the Gulf, said John Cangialosi, acting branch chief overseeing the National Hurricane Center specialists who develop forecasts for storms. Helping reduce the chances of hurricanes along the Louisiana coast this year was an unusual two-month pause in the formation of any tropical systems in the Atlantic between July 3 and August 31, the first time that happened since 1941. Blame windshear in the mid-Atlantic Ocean, in part caused by a long-lasting upper level low pressure system parked over the Bahama Islands, that made it impossible for the tall thunderstorms that spawn hurricanes to form, said Phil Klotzbach, a climatologist at Colorado State University who leads a team that issues seasonal hurricane forecasts. Another part of that pattern is TUTT, which stands for tropical upper-tropospheric trough, an upper level trough of low pressure that was stronger than normally seen during active hurricane seasons. The TUTT condition might have been linked to an unusual difference in sea surface temperatures in the tropical and more northerly subtropical areas of the Atlantic. The differing temperatures that caused in the atmosphere may have triggered the formation of more frontal systems that created the wind shear. That odd pattern reversed what should have been a period of less windshear, which usually occurs when there’s a strong La Nina, a phenomenon marked by lower than normal sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean. This was an unusual third year in a row for strong La Nina conditions, which, along with slightly warmer than normal average sea surface temperatures in areas of the Atlantic where tropical storms form, was in part the reason both Colorado State and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration had predicted a more active 2022 hurricane season.

La Nina is going away but we still has some bad storms, just not here.

La Nina is beginning to disappear, but it’s still too soon to predict whether it will be replaced with warmer eastern Pacific sea temperatures, a pattern known as El Nino, which normally increases windshear in the Atlantic and blocks storm formation, or neutral sea temperature conditions, which has less effect on Atlantic hurricane formation, Klotzbach said. The season still produced several damaging storms: Hurricane Ian, which made landfall on Sept. 28 in Cayo Costa, Fla., as a Category 4 storm with 150 mph winds, and made a second landfall as a Category 1 storm in Georgetown, S.C., was among five hurricanes, including 2020’s Hurricane Laura, ranked as the fifth-strongest hurricanes to make landfall in the U.S. CoreLogic, a property analytics firm, has estimated damages for Ian may total $70 billion, including losses covered by property and flood insurance and uninsured losses, Hurricane Nicole made landfall as a Category 1 at Hutchinson Island, Fla., on Nov. 10, the latest a storm has ever made landfall in Florida and Hurricane Fiona made landfall on Sept. 18 as a Category 1, with 85 mph winds, near Punta Tocon, Puerto Rico. On Sept. 24, Fiona made landfall in Nova Scotia, Canada, as a post-tropical cyclone, still with winds of 105 mph.

We were under the monthly storm averages most months.

Colorado State’s seasonal wrap-up report points out that even the 2022 season’s being average is unusual. The “accumulated cyclone energy” score of only 95 makes the year the first since 2015 that was not classified as above average. At the National Hurricane Center, forecasters already have begun focusing on the 2023 hurricane season and future forecasting needs, Cangialosi said. Part of that effort will involve working with social scientists to eventually reshape the way forecast graphics are displayed to the public, he said. Among those are the forecast cone graphics used to describe the area where a path might occur several days into the future. As the accuracy of forecasts improves, the width of the cone at 3 and 5 days out narrows. The public often misunderstands that cone as indicating where a hurricane’s effects will occur, which often is inaccurate. For instance, while a storm’s eye might fall within the cone, its rainfall pattern, or tornadoes that occur on its outer edges, or the storm surge it creates, often occurs well outside. Often, that misunderstanding is combined with a lack of knowledge in areas not often hit by hurricanes, or areas with lots of new residents, such as occurred along the Lee County, Fla., coast during Hurricane Ian. Residents remembered the last storm that hit them, Hurricane Irma in 2017, as mostly affecting the Florida Everglades or the state’s east coast communities. “Your community is in the opposite camp,” he said of the New Orleans area. “You’re under the gun for lots of hurricanes, and you know what can happen in your community or what happened in nearby communities.” He said: “We need to look at the cone and determine how to use it to help the public make better decisions, and that’s not ironed out yet.”

It was a good season for us.